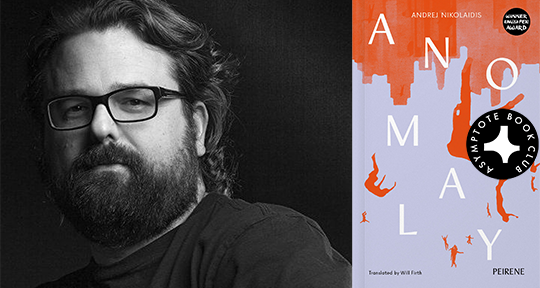

Anomaly by Andrej Nikolaidis, translated from the Montenegrin by Will Firth, Peirene Press, 2024

I am an Apocalyptist. I believe that Good will win out in the end, and when it does, the world as we know it will be abolished—it will no longer exist. So, once that world is gone, Good will prevail. If the concept of the Apocalypse isn’t the ultimate irony, I don’t know what is.

—Andrej Nikolaidis

Andrej Nikolaidis’ Anomaly, published in Will Firth’s translation, begins with a verdict: “The human race owes its history, as well as its future, to the fact that we’ve always been able to turn our backsides to the graves of those we maltreated, and then seek absolution.” Though this has been the case for millennia, the novel insists that human censorship will not be able to preserve its euphemized retellings for much longer. After a freak incident involving “a machine that would give each of us . . . all of the possible scenarios and outcomes of our lives”, past and present begin to merge: a mammoth falls and crushes a man brooding on a quay in Chile; a cruise ship collides with three women contemplating shop windows on Ferhadija Street; a man haunted by an incestuous affair is killed by a cannonball fired in 1805 by Napoleon’s fleet, while praying in the Kotor Cathedral. The truth of never-ending human cruelty—“one drop” of which is “enough to destroy the world”—finally refuses the revisionism afforded to us by the present, and becomes unignorable by physically unfolding everywhere, all at once. Nikolaidis’ very literal rendition of the Book of Revelation is unflinching, darkly humorous, and relentless in its pursuit of the uncomfortable details we tend to suppress.

In 1992, Nikolaidis and his parents fled to Montenegro from his native Sarajevo to escape the mounting ethnic strife that would soon erupt into the Bosnian War; the author, then, is no stranger to the tumultuous experiences at the core of Anomaly. Decidedly anti-war and anti-nationalist, Nikolaidis is also fearless in voicing his views. When his 2006 novel, Sin, was awarded the 2011 European Union Prize of Literature, the announcement detailed how his public defense of “victims of police torture. . . resulted in his receiving many threats, including a death threat during a live radio appearance”. His insistence on “freedom of speech [as] the basis of freedom” is obvious in his literary and journalistic work—and the way he implements this freedom is equally noteworthy.

Within a literature that Will Firth aptly describes as “heavily male-dominated”, and a greater cultural context fraught with “male violence, macho culture and the depreciation of unpaid domestic work”, Nikolaidis creates women characters whose depth and complexity are rare—in both Balkan writing and literature at large. A stark example is the narrator of “Fugue”, Anomaly’s second half: a musicologist fleeing armageddon with her daughter in a Heideggerian mountain cabin, hell-bent on discovering a score composed for the apocalypse by a sixteenth-century madman “who called himself the Revolutionary from the Upper Rhine”. Her journal entries, as frenzied as they are erudite and as obsessive as they are arcane, evoke the archetype of a monomaniacal scholar—a literary trope usually incarnated through a man. Indeed, the beginning of “Fugue” makes it seem as though the male narrator of the first half had simply gone mad during the intermission and switched personas, but this expectation is betrayed when we find that we are actually in the company of a mother, haunted by her daughter’s proximity to death.

The defiance of expectation is a crucial device within the book, and serves not only to question sexist tropes embedded in the reader’s subconscious, but any and all habits of thinking that have been naturalized by rote. Giving verbal expression to the subversion achieved via Anomaly’s textual clockwork, the musicologist rallies against “a life organized according to so-called social norms, which are a veritable firing squad ever ready to unleash a volley at everything unique in us”.

Eventually, the narrator of the first half, “Toccata”, is revealed to be the Devil himself. This pairing of a woman (the Other to the culturally preeminent man) and the Devil (the Other as opposed to God) draws attention to the parallel mechanisms of control and domination coded into religion and patriarchal society, two institutions built upon the rejection and censorship of their respective Others. Notably, both the Devil and the musicologist make reference to the Lacanian Law of the Father—the Devil remarking that the “Christian West” is composed of “the nations of the Father-tyrant” and the musicologist making reference to “the males who rose up against the Law of the Father”. The Law of the Father—a psychological force theorized to exert control upon human desire and communication—is predicated upon censorship, a practice common to the patriarchy, religion, and culture at large. Anomaly lays bare the inevitable failure of this erasure, showing the failures of repression on an individual, cultural, and, finally, cosmic level—with the final breakdown of the universe when “space becomes time”.

Anomaly lends a voice to many characters, some despicable, others tragic, and all of them doomed. Yet the implication of this choice extends far beyond simply showcasing a tableau of indiscriminate violence. Instead, Nikolaidis allows his characters to speak, entertaining their various weaknesses, elisions, and (self-)deceptions, before recounting the same story with details the characters failed to include. In this, the infernal narrator of “Toccata” reveals to the reader their own fallibility. We are initially tempted to believe the man in “The Cathedral in Kotor”, “whom [the Devil] gave the honor of being the narrator, though he in no way deserved it”; his version of the story—where his cheating wife falsely accuses him of having an incestuous affair with his blind sister in order to excuse her own infidelity—is presented as truth, and the chapter’s coda—which finds him kneeling in the Cathedral and addressing his late sister with the words “I wish you could see the cathedral shining, and all of it ringing golden”—enforces this impression. However, religiosity and capital-G Goodness are both revealed to be suspect in Anomaly, just like the man’s narrative. It turns out that he was, in fact, involved with his sister—an affair that resulted in a child and destroyed the marriages of both siblings. “The story therefore centers around shoddily concealed incest, which can’t be obscured by the pseudo-pious ending: Jesus, the cathedral that rings golden, and the other junk”, the Devil notes, shaming those inclined to trust the silver-tongued debauchee.

Nikolaidis’ Devil, like Milton’s Satan and Bulgakov’s Woland, is anti-authoritarian rather than simply evil, and is more aptly a veracity enthusiast than a sadist. His grim, caustic speech, unceremoniously interrupting the characters’ carefully constructed (and highly selective) narrations, is an extension of his irreverence: “your rules of narration don’t apply to us. You’re used to commands, we to confessions”. Confessions, unlike the sterile command, necessarily contain the sinful and ugly, and because the characters confess, there are no perfect victims in Anomaly. Even victims of circumstance aren’t spared from an exhumation of their darker qualities. The poor, venerated in Christianity, are shown to harbor “[s]o much envy, so many fantasies about revenge, violence, abduction and expropriation, not to mention arson and rape”.

This darkness, however, does not disqualify the characters of Anomaly from receiving sympathy; instead, acknowledging their complexity shows that any sympathy founded on idealization is essentially contingent on the persistence of illusion. Such aseptic notions of goodness are satirized via the Peter and Paul duo—two Balkan men who respectively strive to embody Christ by progressively amputating body parts (because the body is the source of carnal temptation) and engaging in necrophilia (to avoid passing on an STI). The antithesis of Peter and Paul’s twisted, censorial ethics is Anomaly’s radical inclusivity, which is found not only on the moral, but also on a cultural level.

The novel is riddled with allusions to works from various regions, time periods, and genres: Hitchcock movies jostle Lacanian psychoanalysis, music theory, and the writings of theologians in this Gadarene text, creating a multiplicity that is neither strictly unitary nor completely open-ended. It is oddly fitting that this irreverent, pluralistic text was translated by Will Firth, who has been involved in the anarchist movement since 1985. Firth’s own profound knowledge of the Balkan region and affinity to Nikolaidis’ resistance to control have contributed to the brilliance of his rendering of Anomaly into English. Through the co-authorship of a translator, Anomaly’s inherent pluralism is intensified, resulting in a collaborative tour-de-force, and a must-read for anyone brave enough to face the “warts and all” truth.

Sofija Popovska is a poet and translator currently based in Germany. Her other work can be found at Context: Review for Comparative Literature and Cultural Research, mercury firs, Tint Journal, GROTTO Journal, and Farewell Transmission, among others.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: