For our final title of 2023, we are proud to present the latest novel by acclaimed French-Lebanese writer Amin Maalouf, whose extraordinary work weaves fantasy and history with a powerful reckoning of contemporary issues. In On the Isle of Antioch, Maalouf turns to dystopian narrative to explore the frailties and failures of human empires, drawing a surreal evolution of events that escalate from the very real threat of total global destruction. With a philosophical richness that finds footholds in Maalouf’s elegant, nebulous depictions of desire and connection, the novel is a beautiful, necessary rumination on what survival means on the precipices of so much devastation.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

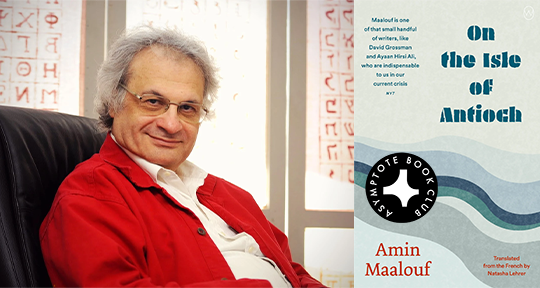

On the Isle of Antioch by Amin Maalouf, translated from the French by Natasha Lehrer, World Editions, 2023

There is something eerie about reading Amin Maalouf’s On The Isle of Antioch during the same days described by its narrator’s journal entries. In four sections, or “notebooks”, that date from November 9 to December 9, Maalouf’s surreal, thrilling novel is told through the experiences of Alexander, an artist and one of two inhabitants on the titular island of Antioch, as he travels in this brief window of time through isolation, doom, communion, and the unexpected orders and disorders of a dying world.

Having inherited the land from his father, who had refused to sell the deed despite financial difficulties, Alexander decides, in the wake of his parents’ death, to change his life. He begins drawing, releasing work under the pseudonym Alec Zander, and moves to Antioch in a reprieve of his childhood fantasies, calling it his “ancestral island.” Believing himself to be the only inhabitant and sole owner, he’s surprised to find, while waiting for his house to be built, that a woman and writer by the name of Ève had long ago purchased the remaining portion of the island that he did not own, and, being “eager for solitude”, she too has made it her home. Ève’s been in a rut, having published one masterpiece—a novel titled The Future Doesn’t Live Here Anymore—before losing her job and retiring to Antioch, where she sleeps all day and is awake all night, trying to work.

What drives these two loners together, after months of avoiding each other’s company, is a sudden blackout. When all the lights and appliances in Alexander’s house turn off, and even the radio plays only an ominous whistling on every station, he goes to see Ève, suddenly overwhelmed by a solitude that now weighs more heavily on him than ever, and feeling “for the first time in twelve years, [that he] slightly regret[s] not living in a town or a village like an ordinary mortal.” Having previously thought of Ève only as a “silent, ghostly, almost nonexistent” presence, it is only after this incident—which turns out to be a full blackout of all communication systems—that Alexander and Ève are able to find themselves in one another’s company.

Maalouf intentionally keeps readers at a distance as to the events raging beyond the island, but eventually, the narrative reveals that there may have become a kind of nuclear war, an apocalyptic end of which, in their seclusion, the two neighbors feel only the ripples. “I have no idea,” Alexander says, “if the oxygen filling my lungs carried particles of death.” Yet though the novel happens in these small, seemingly fringe areas, Maalouf continues to simmer the political drama unfolding elsewhere on the world stage. In the coming days, we learn that the communication blackout was actually caused by a mysterious group called the “friends of Empedocles”, who had initiated it to prevent a nuclear meltdown. The rest of the novel details the interactions between Alexander, Ève, their friends and more distant neighbors, and these friends of Empedocles—handsome but unplaceable looking people with ancient Greek names, and endowed with tremendous knowledge and powers.

The blackout eventually ends, but the impending risk of a nuclear crisis doesn’t, and through a conversation with his friend, Moro, a senior advisor to the US president, Alexander begins to learn more about who these “friends” are, and what they can do. Alexander’s goddaughter, a physician, is curious about the foreigners’ incredible advances in medicine—somehow miraculously making everything “good and new”—and hopes to learn from them, but others (including the president and his advisors) are both suspicious and fearful. Ève regains her prowess, and eventually produces a novel that tells the story of a civilization, which “despite its spectacular advances, is suffering from an insidious sickness that is leading to its imminent collapse.” Some vigilantes eventually take matters into their own hands. People die. Reality gets muddied. Throughout, we, like nearly everyone else in the novel, aren’t sure who to believe, or what will happen.

Amidst these confounding events, Alexander’s writing reveals moments of tenderness and intimacy. His entries offer us meditations on loneliness, the weighing of his growing companionship with Ève, and the strange motion of feelings as they change. “What I do know,” he says,

is that I want to see her all the time, I want to listen to her and to share the myriad thoughts going through my mind. Even when I’m alone, I find myself speaking to her in my head, I picture her jumping up, getting impassioned, frowning. I was sad to miss her this evening. And I would undoubtedly suffer if I were to stop seeing her.

Despite his apparent longing for solitude, a more irrepressible, human desire comes through amidst the procession of total collapse—wanting to be with someone, to talk to someone, to be less alone at the (still uncertain) end of the world.

Maalouf enriches his prose with monologues, reproductions of ancient myths, transcripts of phone calls and messages across different time zones, presidential addresses delivered on the radio, news of demonstrations in cities around the world, letters to the house of representatives, and accounts of various conversations. The novel is thus an archive of communication from the margins of the world, and in this, it mirrors the ways that many of us in the global north have come to log and record major events in contemporary history. Just as an apocalypse flourishes elsewhere, sending its fragments to Antioch, this splintered view is also how many of us experience devastations both contemporaneous and abstracted—earthquakes in Turkey, Syria, Morocco, and Afghanistan; the ongoing Israeli genocide of Palestinians; the atrocities inflicted on the people in Sudan amidst the war between the army and paramilitary forces; the horrific working conditions and mass murders in the Congo; and the displacement of millions and the destruction of entire ecosystems. All this, too, comes to us with both urgent immediacy and a tragic helplessness—each event heralding, in its own way, some sense of the end days.

Reading On the Isle of Antioch thus offers us an opportunity to think about our positionality as the world unravels over and over—to think about both the immediate, human experience of these crises, and the transference of them, once or twice removed, through records and reports. The story necessitates a consideration of our social and physical environments, the ways we are affected by global turmoil, and—as we witness the relationships evolving between the foreign visitors, the townspeople, and the islands’ inhabitants—how we all come to be implicated in a perpetual end-of-the-world. Through Alexander’s entries, Maalouf is able to express the candour and intensity of feelings in the middle of their development, building an archive of liminality of someone continually trying to process, to make sense of events that have no sense, to hold on; he offers us a human way to experience cataclysm without masking the confusion and desperation that takes hold, and refuses to pretend that any of us will remain unaffected.

What results is a novel that feels remarkably contemporary, translated by Natasha Lehrer into an English that captures the depth and breadth of a mind living through global catastrophe, but which also brings back remnants of the alienated, confounding sentiment that dominated essays and statements during the Trump era and the pandemic years. On the Isle of Antioch, while offering us a mirror to think through the horrors and absurdities of our own reality, alerts us to the treacherous nature of complacency and our tendency towards normalization, and does so by showing us the myriad ways that world-changing events constantly overlap with our own mundane ones. When entire futures start to disappear in the distance, Maalouf warns us, our own is not too far behind.

Ruwa Alhayek is a Ph.D. student at Columbia University, studying Arabic poetry and translation in the department of Middle Eastern, South Asian, and African studies. She received her MFA from the New School in nonfiction, and is currently a social media manager at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: