The latest text from one of German New Wave’s founding members and all around heavy-hitter; a wide-ranging compilation of art and testimony championing the Iranian feminist movement from Marjane Satrapi; and a moving, braided narrative of grief and recovery from a lauded Icelandic author. Our editors review some of the most exciting works in translation coming to the Anglophone this month.

The Book of Commentary / Unquiet Garden of the Soul by Alexander Kluge, translated from the German by Alexander Booth, Seagull Books, 2024

Review by Bella Creel, Blog Editor

Filmmaker, author, and philosopher Alexander Kluge’s most recent oeuvre, The Book of Commentary / Unquiet Garden of the Soul, is an act of rethinking. Born in Germany in 1932, Kluge blurs the edges of the many years of his life in this ambitious work, expanding beyond the first-hand, beyond generations, drawing connections between now and before, all in order to fully describe the experience of a single life. Alexander Booth offers a wonderfully dense and witty translation from the German, with no aversion to a confusing syntax that demands rereading and rethinking.

Kluge is trying to find the right words throughout this collection, which, in the process of its creation, must have been turned over and inside out, stretched to snapping and magnified to the molecular; reading it, in turn, requires a certain liquifying of the brain. This giving-in allows one to absorb the words, which only then can be reformed into some sort of meaning. Kluge himself seems to follow a similar process:

Where does all my ‘fluent speech’, my rabid desire to write, come from? I listen to others. And carefully! A word that flies towards me, an observation that charms me into conversation, a quotation that I read: all of this gets stored inside me for the long-term.

I usually tear books to shreds, marking any places that captivate me in colour pencil before ripping the page out. These I attach to other findings of mine with a paper clip. They’re often annotated. My flat is full of these piles of paper. My personal bastion against the ‘ignorance that shakes the world’.

Those paper clips that join Kluge’s observations together are naturally lost in the translation from thought to text. The connections drawn between events are less exposited than implied, and it is the responsibility of the reader to mimic Kluge’s close listening. In a short entry aptly titled “Reading Instructions”, Kluge offers some advice:

Turn the word around in your mouth, turn it around on all sides and flip it over. Examine the words with your eyes, compare the word with the greater area of its neighbouring words . . . if the reader has made friends with a word (they have noticed it, have anchored it in their memory), they should have that word in mind when reading one of the surrounding stories.

As if to emphasize that The Book of Commentary / Unquiet Garden of the Soul is a book not only to be read, but reread, Kluge refrains from mentioning this guideline until page 193. It comes towards the end of Station 8 (as the book is composed of twelve stations and concluding notes), following a non-exhaustive exploration of Freud’s ‘cap of hearing’—the name for what sits awry atop the ego, and the function through which perception becomes comprehension. In Kluge’s words and emphasis: “THAT WHICH SITS AWRY, LIKE A ‘CAP OF HEARING’, IS LANGUAGE.” Language, imperfectly, is our ability to transform the cacophony of experience into meaning.

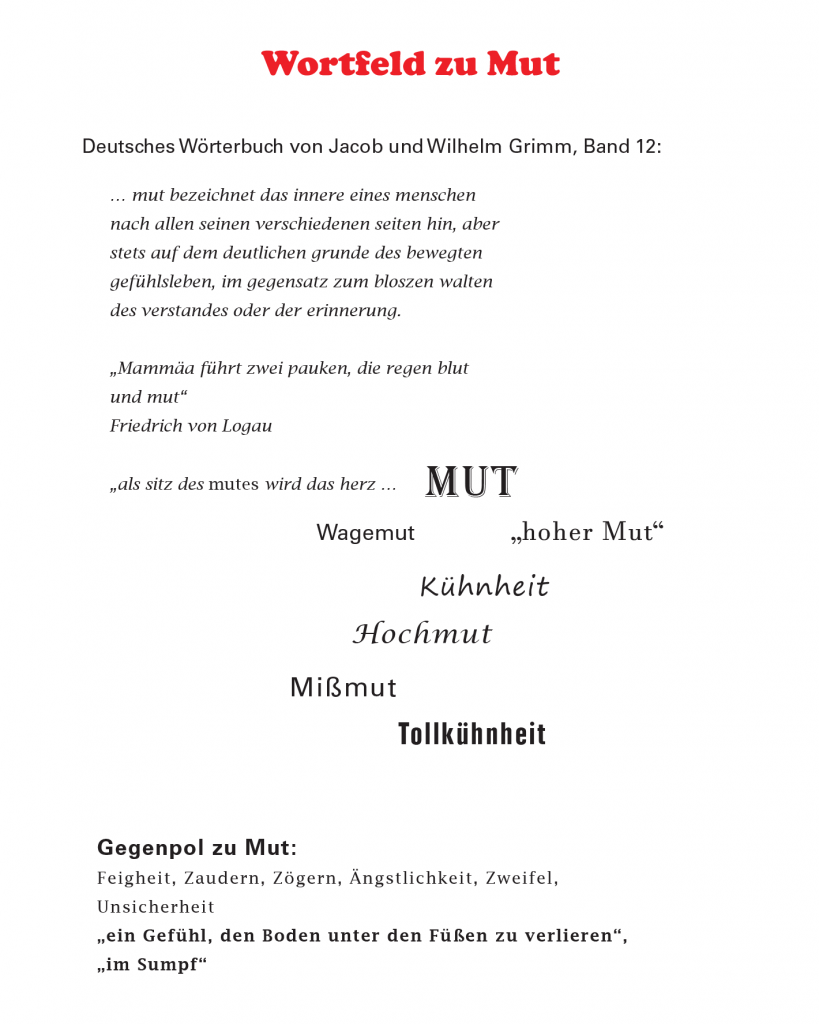

Kluge and Booth do not limit themselves to the German and English languages in the endeavor to represent experience, nor are they always concerned with grammar and universal comprehensibility. Kluge is fascinated by ‘semantic fields’, collections of words related in some way. They are featured throughout the book in the original German, with only the titles translated into English. They’re quite beautiful. I do not speak German, but when I read over a semantic field, certain words might remind me of an English term, or the category leads me to extrapolate. I think: In the semantic field for ‘courage,’ there must of course be ‘brave’. But really, must there be? In Kluge’s semantic field, I think there is an excerpt from a Brothers Grimm story; I conclude that ‘Mut’ must mean ‘courage’. But I have to think, and I don’t truly know. Within the gap between what I know and what I assume, there are endless possibilities; to approach Kluge’s understanding, I must construct my own semantic field.

I often found myself thinking that I am entirely out of my depth for a book of this breadth. I’m sure someone who is more knowledgeable of Freud, Greek mythology, Jürgen Habermas, first-hand experiences of the Second World War, the history of Corinth, the Davos Debate, the inner workings of Silicon Valley, pilot fish especially, and every moment of Alexander Kluge’s life would have a much different experience of this text; perhaps such a reader might even understand it. But the unique experience and prior knowledge that each reader brings to a text simultaneously draws them away from it, as what they are told is obfuscated by what they already know. True understanding is a monumental task, so daunting that it inhibits one from listening in the first place. But this is all we have, and we have to try—so said by Kluge himself:

I apologize again for insufficient understanding. But what have I got besides that, what’s at my disposal? Courage. And that’s got to be enough affectively and in terms of ideas. Otherwise, I would be unable to express myself.

Woman, Life, Freedom, created by Marjane Satrapi, translated from the French by Una Dimitrijević. Seven Stories Press, 2024

Review by Daljinder Johal, Assistant Managing Editor

When looking at today’s news cycles, their scattered, exponential offerings provide a challenge for those seeking to keep up with—or understand—world events. The attempt to identify relevant historical contexts, acknowledge the inevitable complexity of human nature amidst global conflict, and come close to something akin to ‘truth’ can all feel quite fruitless; after all, there is never truly one complete version of the truth. Despite these innate obstacles to true comprehension, however, the graphic storytelling of Woman, Life, Freedom builds a strong case for art as an effective method of showing multiple perspectives on current events. In this case, the work covers a series of protests in Iran, engaging a non-Iranian readership while providing a sense of solidarity for Iranians all over the world. Where journalism can reach for the facts, the art of this graphic novel both serves to educate and inspire emotion in its reader.

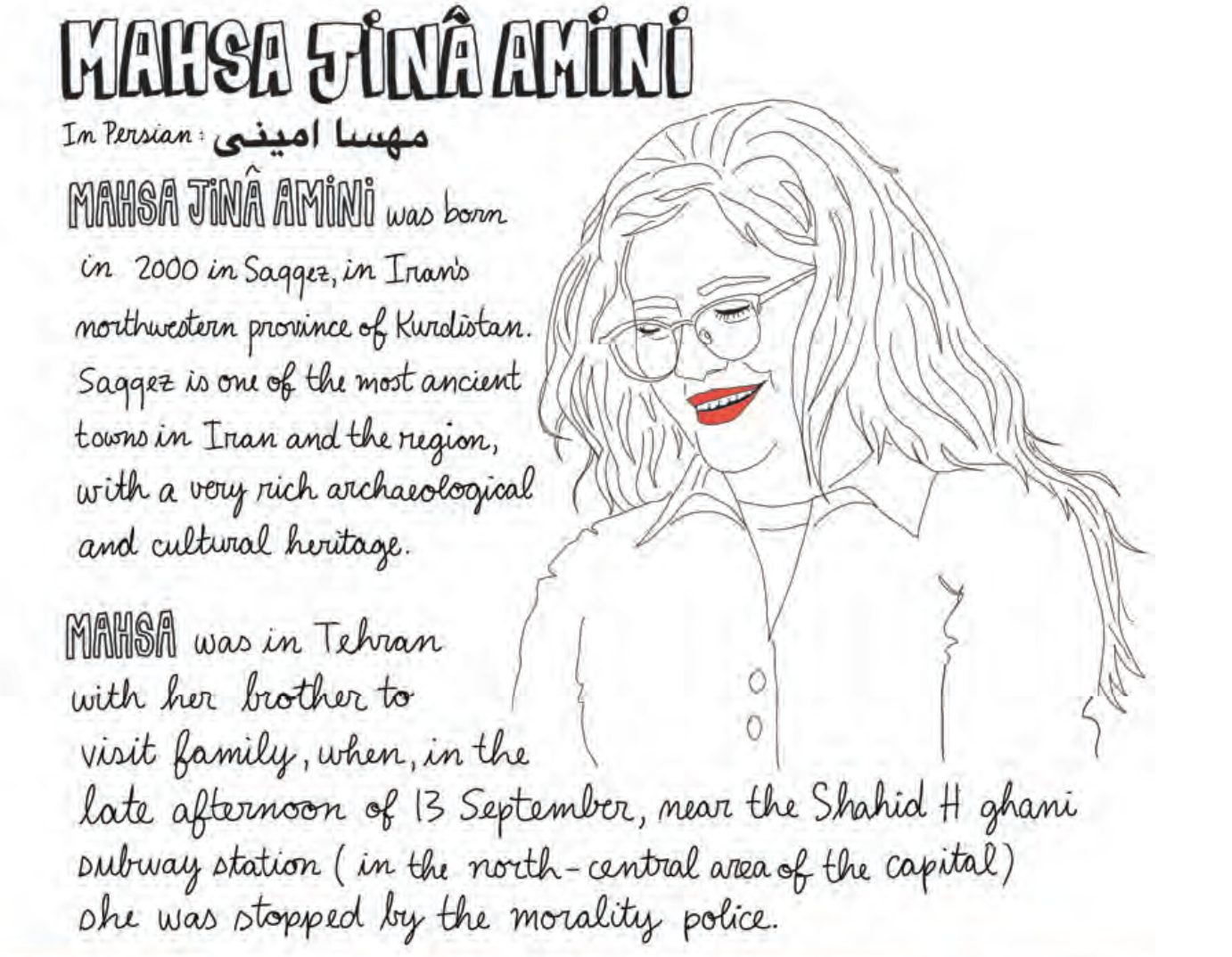

On September 13, 2022, a young Iranian student, Mahsa Amini, was arrested by the morality police in Tehran. Her crime was improperly wearing the headscarf required for women by the Islamic Republic. At the police station, she was beaten so badly that she had to be taken to the hospital, where she fell into a deep coma. She died three days later. Following this tragedy, a wave of protests spread through the whole country with crowds adopting the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom”—words that have since been chanted around the world during a profusion of solidarity rallies.

But for Iranian people, this wave of resistance was not entirely unexpected. As a collaboration of over twenty activists, artists, journalists, and academics, this graphic novel depicts the present Iranian feminist revolution as well as the events leading up to this historic uprising. In presenting such an alliance of twenty different creators, even the collection’s form affirms its rebellion; whereas the Iranian regime necessitates uniform submission from its citizens in an unequal and oppressive hierarchy, the various creators’ unique perspectives and styles have here come together to form a cohesive and compelling piece of work. Their differences strengthen, rather than undermine, their shared aim.

Split into three parts—The Events, A Bit of History, and An Iron Regime… A People Resisting—the collection looks at the present, past and future possibilities of Iran, with a distinct selection of comics in each section. The styles and tones of the comics frequently shift; for instance, “Sparking a Revolution” takes the form of a Q&A on the subject of Mahsa Amini’s death. Within this diversity, choices in style and form always feel purposeful and thought-out throughout this text, allowing readers of all knowledge levels to grapple with the basic facts of life in Iran, such as the presence of the morality police, or why the veil is a focus within the “regime’s DNA”.

Other elements of the first section are equally functional, shedding light into the origins of the slogan “Woman, Life, Freedom”, or tracing some of the music that has galvanised this movement, such as Shervin Hajipour’s song, “Baraye”. In building this daily picture of Iran, the editors also make a clearer case for this collection’s necessity; the Iranian regime’s arrest of Shervin Hajipour and deletion of the Instagram post for “Baraye” demonstrates the suppression of freedom of speech in any form. It’s easy to imagine the exhaustion of living under such omnipresent censorship.

The second section of the collection outlines practical facts, such as the turbulent history of Iran. As stated by Hamoun and Abbas Milani, its citizens have lived through “three major political upheavals, and at least three (if not six) revolutions” over the last century. Yet, the text balances stark fact with humour, its comic style bringing to life a breakdown of ‘Who Rules Iran?’ or the ‘Madness of Censorship’. In the former, the many-legged depiction of Iran’s Supreme Leader, Ali Khamenei, is comparable to any comic book villain, yet the authors make clear that Iran’s troubles do not lie solely with this man, but also those who are represented as his legs, carrying out his bidding. Equally, a tongue-in-cheek approach explains some of the operative hierarchies in Iran with a recipe for an “Aghazadeh”, or “blue blood”. Primarily, these “rich kids of the regime” are “the ultimate symbol of corruption and injustice”, as they embrace forbidden Western practices but remain unpunished—being the children of rich and often hypocritical politicians and oligarchs.

This humour also allows a careful exploration of the ongoing situation’s complexity, as well as the few choices left to Iranians. Amongst those who remain in the country, there is a massive gulf between the Aghazadeh—who purposefully ignore or participate in corruption via bribes—and the Iranians who risk their safety and freedom by participating in protest or increasingly, even simply by trying to survive the everyday.

There are also those who leave the country, adding to Iran’s “brain drain”. But, as the third and final section explores, this growing diaspora is just as uncertain as many non-Iranians regarding the true situation of their home country and how to unite—or even ultimately bring down the regime. Though they may have found a home outside of the country, their actions abroad may still be discovered and denounced by the regime, risking the livelihoods of their families left in Iran.

Nevertheless, as this final section imagines the future for Iran, the comic with the most minimal dialogue inspires true hope. In the “Art of Rebellion”, written and drawn by Deloupy and Farid Vahid, we see a young woman simply go about her day with “small acts” of defiance: “living alone, being single . . . going for a run, wearing make-up, painting my nails, having a piercing or tattoos”. But, as the comic concludes, such acts are “far from trivial. As the famous Persian proverb goes: ‘the ocean is made up of single drops’”. And perhaps, in this book, one will find another such droplet of rebellion, which will come to play a part in dismantling the regime it seeks to call attention to.

Your Absence is Darkness by Jón Kalman Stefánsson, translated from the Icelandic by Philip Roughton, Biblioasis, 2024

Review by Kathryn Raver, Assistant Managing Editor

A man finds himself in a church. He has no memory of how he came to be there, nor does he remember his own life, or even his own name. He leaves, then, with nothing but the words of an ominous stranger—the only other occupant of the church—to guide him: “But keep in mind that sometimes life is the questions, death the answer—so tread carefully, mortal!”

Thus begins Jón Kalman Stefánsson’s Your Absence is Darkness, the latest offering in English from an author known for telling incredible tales of rural communities in Iceland. As in his other novels,music, religion, philosophy, and death are all interwoven here with stunning imagery and the threads of so many individual lives, creating a complex tapestry full of love and loss that spans generations. This novel is, firstly, a tribute to the people and landscape of Iceland, but on a larger scale, it is also a tale about life, death, and what we do with the time we are given in between the two.

The storylines throughout are broken up and interspersed, overlapping one another as Stefánsson throws chronology to the wind; we may see a character’s gravestone on one page, only to meet them in their home a few pages later. This is done, however, with distinct purpose. This is the story of a land and a community told by the land and its community, and everyone has some measure of grief, or loneliness, or occasional joy to contribute. This puzzle-piece approach also allows the narrative to unspool with measured expertise, revealing the connections that exist among seemingly unrelated characters, bringing us full-circle in the end.

This is, consequently, a character-driven story rather than a plot-driven one—though this focused approach does not take away from the narrative’s impact. Stefánsson takes everyday encounters and emotions from chance to fate; sometimes that fate is tragic, sometimes beautiful, and often both. In taking the time to focus on each character’s emotional arc, Stefánsson manages to capture the fine nuances of grief and yearning that we, as the readers, must bear witness to. Such details are so often glanced over in favor of plot, but through these authorial choices, lives that would ordinarily seem mundane are lent a new emotional depth:

…tell us, which is nobler, to suffocate the voices of the heart in the hope that the world will remain unchanged, or to cling to emotions, surrender to them and simultaneously transform existence into uncertainty?

Stefánsson puts a great deal of care into his descriptions of setting as well as character. In spite of the arguably ordinary nature of the places present in the novel, they are recounted in a way that lends them an almost mystical quality. A heath that a woman crosses on her way to a life-changing encounter, for example, is not just a heath, but something transformative:

Heath, it’s a beautiful word…though sometimes meaning the same as loneliness, bad weather, hardship, and fog you get lost in, but it also means freedom, tranquillity, and dreams.

Many times throughout the novel, the characters draw readers further into the narrative by speaking directly (though inadvertently) to them. We are privy to their letters, or—in the case of the central narrator—private conversations with enigmatic figures. The sudden switch to ‘you’ in these moments, where the rest of the novel alternates between first and third person points of view, diminishes the distance at which the reader can hold the story, forcing us to consider the existential questions being raised by the narrative on a more personal level. The author seems to assure us:

Of course much is unclear, and of course many questions are unanswered. That’s how it must be. You know that as well as I do. Otherwise, we have no reason to continue.

One of the questions that the novel seems to ask—amidst the many of the amnesiac narrator—is what the big picture is, amidst all of these tiny threads. In the grand scheme of things, what is the point of all of our grief and hope and suffering? Where does it lead us? Perhaps the answer that Stefánsson seeks to evoke is that the big picture isn’t for us to know, but something that is created, unknowingly, over the course of centuries. We, as individuals, live only here, in the day-to-day, with the unknown always beside us, unreachable.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: