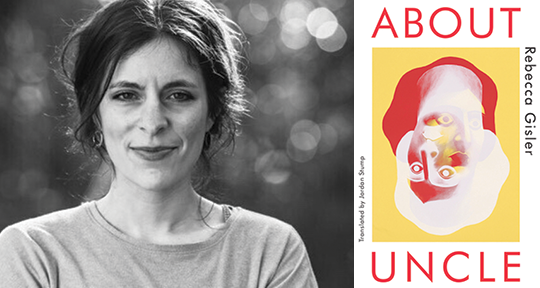

About Uncle by Rebecca Gisler, translated from the French by Jordan Stump, Two Lines Press, 2024

About Uncle is Swiss writer Rebecca Gisler’s debut novel, translated by Jordan Stump—a dazzling and intoxicating story that takes a microscopic view at the banal and unnerving details of family dynamics. A love letter to the oft hidden odd and grotesque mannerisms of our family members, About Uncle boils over with emotional distress, set just on the verge of the first COVID lockdown in spring of 2020. But, it’s not COVID that sets the tone, it’s everything else: family at its most banal, at its most crude, with an emotional tinge humming with tenderness.

At the center of the story is the unnamed narrator’s uncle, a 52 year-old recluse who seems to thrive among the squalor and filth built up over 30 years of hygienic apathy. In an unkempt house in the Brittany region of France, Uncle lives with his niece and nephew as “a congregation of do-nothings.” The siblings struggle to balance their personal struggles with their shared concern for Uncle’s health and lifestyle, and the “involuntary flatshare” is the centerpiece of a claustrophobic world that quite literally reeks of death and decay.

Uncle’s rugged personality and indifference are reflected both inside and out, as we learn that the garden is unkept (at the insistence of Uncle), the ivy is taking over the walls (at the insistence of Uncle), and numerous ineffective mole traps litter the lawn (at the insistence of Uncle). It’s not until Uncle is diagnosed with a pulmonary embolism that panic and exasperation from his poor lifestyle choices ignite within the family—disgust and resentment that the siblings had been quietly carrying for months bursting into child-like tantrums.

It’s the pungency of this story—the characters, the house, Uncle’s habits—that keeps us locked in tight, made visceral by Gisler’s sharp voice and Stump’s translation. The opening sentence is both surreal and alarming:

One night I woke up convinced that Uncle had escaped through the hole in the toilet, and when I opened the door I found that Uncle had indeed escaped through the hole in the toilet.

Though it’s not so much surrealism that dictates the substance of the story, but Gisler’s hyper-realization of the emotional context of Uncle’s habits. Gisler writes with a breathless quality, as if the narrator ran into her room to write this novel before the world collapsed, as if pulling these memories from her psyche against time so as not to lose them. More often than not, sentences become paragraphs, peppered with dialogue—there’s a palpable urgency in this voice, a restless rhythm that seems to be racing to the finish line. But as the story unfolds, it becomes clear that there is no real finish line, but rather a compressed moment in time where the banal proved so monumentally consequential it was incredible. While the emotional truth of this memory is desperate, Gisler shows that not all memories are accurate. It seems as if the narrator isn’t confident in her memories’ veracity—“I think I remember that that April afternoon I was reading My Friends, by Emmanuel Bove . . .”— but in their emotional quality.

The rhythm and pacing are where Jordan Stump’s translation skills really shine. The words flow and bounce off each other as if originally written in the English language, demonstrating a mastery of lyricism and style in short fiction. Stump acutely reflects the quotidian mannerisms of the French language; he’s keyed into the intimate ways in which one relates to their native tongue, incorporating slang and colloquialisms that are often impossible to translate.

A very considerate index is offered towards the end, giving translations of some of France’s cultural abbreviations, acronyms, and musical groups. Though some of these explanations aren’t narratively imperative, it demonstrates Stump’s continuous devotion to giving context to Gisler’s French setting. Through close attention to the original French and poignant word choice, Stump produces a voice that draws the reader in and feels second-nature to the unnamed narrator.

There’s no denying About Uncle is kafkaesque, whether it’s a slight nod or a complete dedication to the nihilistic and grotesque in Kafka’s literature. At one point, the narrator mentions Kafka’s very short story “The Cares of a Family Man,” a story about an indefinable creature named Odradek; though Gisler’s characters are all human, it’s clear that the monster in this story is Uncle. Throughout the novel, the narrator presents Uncle as an animal-like creature that survives on organic matter on the precipice of rot, who basks in the excrement of life, and whose emotional intelligence seems is that of a boor.

In normal times, when Uncle was working, he washed once a week, and with any change in routine, vacations for instance, Uncle stopped washing altogether, so when he didn’t have work, Uncle let his beard and hair grow, and he never changed clothes, which is to say that he slept in clothes he’d worn to go to the supermarket or shoot his bow, and he woke up at seven at night and three in the morning, and he stuffed himself with cookies and slices of andouille, and he smelled bad, as you might expect, and he smoked, and he drank beer . . . and every Sunday afternoon at five, he ran a bath, and every Sunday afternoon at five Uncle slipped his fat, pale body, at once flabby and stuff, into the tiny bathtub . . .

The “nothingness” that often drives the emotional conflict in nihilistic stories is present in this one as well, found in Uncle’s experience of the world. Viewed from another angle, perhaps Uncle might be Kafka himself—a man entranced by the morbid mundanity of everyday life, “dazzled by the wealth of items on offer in the bargain aisle,” and so fascinated by “the doings of the local fauna” that he writhes in rage when there’s an attempt at manicure.

Death, decay, and disease permeate the story. They are what provide the contextual fabric—and what allow us to better understand Uncle. Uncle cooks with nearly rotten squid:

. . . and after Uncle has been in the bathroom we often find a wad of brown-stained cotton on the floor or the rim of the sink, and no one knows where that mysterious compress comes from… but as of a few weeks ago, our minds are made up, we’re not going to eat any more squid.

He lacks proper hygiene skills, if not the basic will for cleanliness:

I was expecting to find dead mice and cockroaches in the armoire among my uncle’s underwear . . . but my brother said no lifeforms could have survived in that room, not a single one, except Uncle.

Most of his family members have died from diseases—“cirrhosis, anal cancer, kidney failure, and suicide.” Their local beach is essentially off-limits for locals, a beach adored for its “beautiful red crabs and where there are now only anonymous little crustaceans, translucent, as if worn down by the oily backwash, weary from picking their way through the wads of peat.” Gisler offers a portrait of a desolate town wherein lives a desolate man, just on the precipice of death. Everything that surrounds him is death, and everything that comes from him is death, blurring the lines between self and surroundings.

Uncle is a curmudgeon—the kind who relishes in a past where life was once glorious, spontaneous, inconsequential, and seemingly endless. The kind who seeks to live in the years of splendor—when friendships might not have been abundant, but were fierce. Throughout the story, we learn that Uncle is a certified horticulturist, who gardened for the local church and later became a vegetable-prep man; who loved heavy metal during the 80s and his best friend Manu; who drank and laughed generously with his father; who, when his parents passed away, retreated to his room for solace—his room, his only refuge, that would carry him on for decades.

Gisler knows how to highlight the sympathetic sides of Uncle in a way that doesn’t come off too sentimental. Even though her rendering of Uncle is often frustrated and ashamed, she offers us a space to consider that indeed, we all have met someone like him. In the slow reveal of what Uncle has lost and become over the years, Gisler shows that sometimes it’s not sympathy or empathy these people are looking for, but company: someone to watch the television with, someone who cooks your omelettes, someone who cleans your mess in the bathroom, someone who takes you to the hospital and brings you back home. Someone who shares the kind of love you never fully expected to have. At times it feels as if the siblings are living within the orbit of their uncle—they observe, quietly judge, and design their days around their Uncle’s needs. Despite any disdain or disgust, it’s clear that there is companionship among the three—Uncle loves his nephew and has a much softer spot for him than his niece, something the narrator never criticizes but has clearly felt, as the one who usually cooks for him and is the first to notice when he’s gone missing.

Their orbit around Uncle is quiet and structurally sound, put into stark relief when Uncle’s health threatens to take it away. The siblings, when watching TV, sit behind Uncle, not only as a way to maintain distance but also as emotional protection. These moments, watching TV together yet apart, show that Uncle—a curmudgeon who lives off of solitude—is perfectly content knowing there are a pair of youngsters who’ve quite literally got his back. And when the siblings, who’ve stayed with Uncle despite it all, are faced with what it would mean to lose their source of stress and disgust, they find that family—gross, mean, and intimate family—is still family.

Sharon Beriro is a writer and producer living in the United States. She is a lover of literature and Criterion Blu-Rays.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: