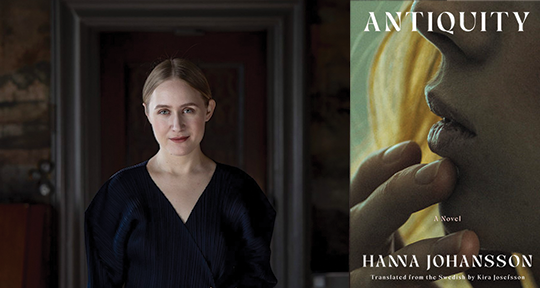

Antiquity by Hanna Johansson, translated from the Swedish by Kira Josefsson, Catapult, 2024

“Where were they?” asks the nameless protagonist of Antiquity, Hanna Johansson’s gorgeous, lacerating debut novel, translated from the Swedish by Kira Josefsson. She is interrogating the lack of cemeteries in Ermoupoli, a luxurious Greek city where she spends her summer with Helena, a chic and volatile artist with whom the narrator is infatuated, and Helena’s sixteen-year-old daughter, Olga. In a city where “the dead should be more numerous than the living”, there seems to be no trace of “such monuments, not even a site for simple graves, no memorial grove in the little park in front of Saint Nicholas Church where the cats slept in the shade of the pine trees.” “Where are they?” she asks of both cemeteries and the dead, not realizing that it is she who haunts the suggestively-named Persefonis—“the short street where Helena’s house was wedged between an alley and a ruin”. Ever on the margins of life, of human relationships, the spectral narrator might touch other things and people, but she never leaves a trace. Throughout the novel, the wounded lament of this reluctant nomad begins to haunt us, too. And this is not only because she is undone by the very skill that enables her to tell a story—narrating—but because Johansson’s creation, in Josefsson’s translation, reminds us of our own tendency to narrativize life, to write ourselves out of the intimate joy of immediate experience by stepping back and fiddling with the details, fashioning an ideal self.

Antiquity feels destined to be a classic, as multifaceted, revealing, and transformative as works by Dostoyevsky, Mann, and Nabokov. Its power comes from its vulnerable, gorgeous prose, replete with lush images, and also from its structural sophistication—a complete convergence of shape and themes. The textual body of the novel is a monument to the clash between the natural flow of life and its narrativized counterpart, felt through the temporal textures of the story, its narratological conflict. In narratological terms, the novel’s fabula—its narrated structure—opens at the end of its syuzhet—its chronological timeline: the narrator, Helena, and Olga are leaving Ermoupoli, heading towards an inevitable separation. As they depart in a ferry, the narrator says: “I could hear my own voice narrating: the sun was so strong you always had to squint a little. I felt reality take its leave of me. I wasn’t there.” From the very start, it is clear that the novel’s tension will emerge from the ebb and flow between the lived truth and the narrator’s censorial customization of real experiences as a constructing of the self. This becomes especially palpable in the chafing of the chronological flow of events against the narrator’s private perception of time. Her narration moves backward and forward in time, then further backward still, only to reemerge somewhere after the middle and then proceed all the way to the end—that is, the beginning. The unpredictability of the temporal jumps precludes anticipation but heightens the sense of foreboding with which the beginning’s manifestly melancholy departure taints all subsequent pages; as in a Greek tragedy, the reader can sense the protagonist hurtling towards a bitter end.

Antiquity’s removed, elliptical style and the incongruity of fabula and syuzhet establish a tangible distance between the narrator and the reader. The reader feels the gelidity of alienation from the narrative throughout, but the narrator herself is even more estranged from her own story. She remains an observer, sidelining herself in her own telling in favor of multiple meaningless romantic obsessions and flimsy friends. Her speech is clipped, tense, almost reticent, and Josefsson’s translation powerfully renders the novel’s hollow, lack-crazed, and obsessive voice into English. This voice becomes haunting, unforgettable as the narrator’s meek adoration of Helena and her tortured jealousy of Olga transform, leading to a shocking turn of events as she discards the artist and begins a romance with the daughter. Johansson deftly crafts a character who flounders in guilty longing like Death in Venice’s Gustav von Aschenbach and remains as recklessly unaware of her own depravity as Lolita’s Humbert Humbert. Like Wuthering Heights’ Heathcliff, she is brooding and codependent, enacting a drive “to find my place, to find my place in the world at last” through a doomed and dooming romance.

Her need for belonging manifests as a hunger for familial closeness. Helena and Olga become unwitting surrogates that satisfy this need—“in Ermoupoli, a mild atmosphere reigned, a sort of intimacy I’d never known in my own family but which nevertheless felt familiar”—but Helena’s volatile mood swings and cycles of affection and distance eventually sink the narrator into “the humiliation of realizing that I had expected something in the first place, something I hadn’t been able to put into words”. This disappointment only exacerbates her already-present feeling that she is a permanent outsider, forever barred from intensity and intimacy, and the attendant sense that she is always intruding upon others’ intensities and intimacies. As the three women take a seashore stroll, she reflects that “Helena and Olga were walking ahead of me, arm in arm, complexly linked. Behind them I felt like a stranger, someone who had picked two people at random to trail, a menacing shadow”. This scene is bivalent, irreconcilable in an agonizing, disarming way. Both her experience of isolation and the shame she feels at coveting intimacy resonates with the all-too-common sapphic fear of being ostracized as a “predatory lesbian” when the reciprocity of attraction is unclear, but when the narrator later begins a relationship with the teenage Olga, it retrospectively imbues the image of her as a “menacing shadow” with prophetic significance. What adds to the scene’s ambiguity is that the romance seems to spring from the narrator’s feelings of alienation; as soon as Helena’s love proves flimsy, Olga’s loneliness becomes beguiling, effacing the embarrassment of rejection for the narrator.

The narrator’s willingness to exploit a lonely and troubled teen is inextricable from her impulse to narrate—she constructs her story and her self by transforming the fragments of her personal history into a narrative that suits her, casting others as supporting characters that illuminate her selfhood. She seems oblivious as to why “each of my romantic relationships had left me lonelier than I was before, in a way I didn’t quite understand”, but the answer can easily be found in her solipsistic vision of love as self-construction and -curation, which she describes in lucid detail even as she fails to recognize the damage it does to herself and others. “I was looking for someone who could reflect me back to myself. I was looking for someone who could bring me into their world”, she explains, later adding, “I was never as interested in the other person as I was in the person I became in their eyes. And when I’d stopped being someone in their eyes, or when I no longer wanted to be the person I was to them, there was nothing left”. She yearns for a lover who will bestow a sense of identity and belonging upon her. After losing all photographs of her past partners, she doesn’t mourn the loss of shared memories. Instead, she welcomes the opportunity to refashion the past into a fictional autobiography: “There was no longer any evidence of this period in my life. Now I could create my own narrative about it; now I could create a new life for myself”.

The narrator’s autobiographical revisionism shows its sinister side when it assumes the shape of a taboo romance with Helena’s daughter. Olga has a history of mental illness and struggles to come to terms with her isolating, sheltered life and her mother’s misapprehension and possessiveness. She “made no friends. Olga became depressed. Olga developed strange phobias. . . You couldn’t get ahold of her anymore. She didn’t pick up her phone”. She is furtive and uncomfortable being present. She “often walked off. Olga ate fast. . . She was quiet. She was shy”. The narrator witnesses Helena’s dismissal and aggression towards Olga, watching as “Helena grabbed hold of her neck, held her still. . . you can’t go somewhere without telling me, it’s impossible to trust you, it’s impossible to love you when you are like this”. As Olga’s friendship with the narrator intensifies, she seems to open up. The narrator notes that “[s]he changed. She got excited talking about herself when I asked questions, my own questions, no longer hers reflected back at her. She stumbled over her words, rushing to get them out”. But this emergent sense of self-possession disappears when Olga and the narrator first kiss: “We merged in the mirror. When I looked at her it was as if I saw myself”. A sense of disquiet arises from these sentences, as the narrator subsumes Olga’s personhood. This impression reaches a critical point when Olga and the narrator have sex, free as it is of any indication of Olga’s consent: “She: stiff at first, still, then soft. A look of overwhelming imploration, almost fright”.

Reconstructing her journey to Ermoupoli as driven by ‘fate’ towards a liaison with Olga rather than her obsession with Helena, the narrator revels in newfound meaning. Meanwhile, their secret entanglement leaves Olga as empty as the narrator has always been. Even cradled in the narrator’s arms, “all she could do was repeat, again and again. . . I have nobody, I have nobody”. Had she been less dazed by her self-narration, the protagonist might have cared that Olga was an unloved child, not seeking romance but rather a space to be herself around someone who would simply listen, without imposing their own rules and expectations on her. While her tentative emotional openness suggests that Olga felt seen by the narrator, this feeling was a tragic illusion; the narrator was looking at their merged reflection in the mirror, Olga reflecting the narrator back to herself, her new narrative refracted through Olga.

The narrator’s empathy fails to reach beyond this conflation of Olga and herself: “I saw my own loneliness in her. I saw myself in her. I grieved the fantasies that left me as we traveled through the dark”. This relationship, like the others before it, leaves the narrator lonelier, failing yet again to fashion a satisfying story out of others. She cannot, ultimately, achieve the boundaryless intimacy she craves; she cannot make a self in the space between Helena and Olga. Ultimately, still, “[t]hey had their names and their boundaries, mother and daughter. I had nothing. I was a stranger. I remained a stranger. I would vanish as strangers do. I had already begun to vanish”. The novel ends with her solipsism reinforced rather than attenuated, in the process of effacing yet another snapshot of her past, creating yet another chapter of her fantastical autobiography: “I was no longer in my own body. I was in the story I was telling myself. I was preparing a memory for later. For three days on the square they’d been showing the world championships in harpoon fishing on a screen in front of the city hall. And there was a thunderstorm, a couple of nights later there was a thunderstorm. That’s how it happened”.

Sofija Popovska is a poet and translator currently based in Germany. Her other work can be found at Context: Review for Comparative Literature and Cultural Research, Tint Journal, GROTTO Journal, and Farewell Transmission, among others.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: