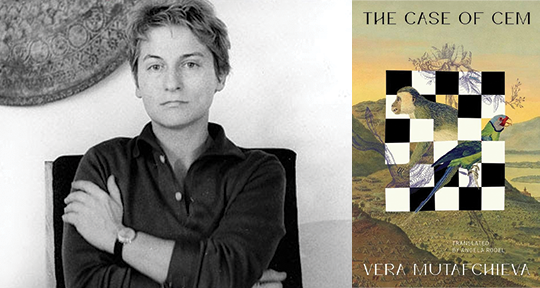

The Case of Cem by Vera Mutafchieva, translated from the Bulgarian by Angela Rodel, Sandorf Passage, 2024

Cem—born in the burgeoning Ottoman Empire, the second son of the legendary Mehmed the Conqueror, and in the eyes of history, the exiled prince. In his time, Cem was lauded by storytellers the world over for who he might become and what he might accomplish, until finally he was pitied for all that he endured. But these portrayals of Cem, some true and others exaggerated, have all but faded from the public eye over time—a fact that renowned Bulgarian author and historian Vera Mutafchieva sought to remedy with her comprehensive account of his struggle in her novel, The Case of Cem.

Mutafchieva’s works have been published in nearly a dozen languages, the most recent being Angela Rodel’s English translation of The Case of Cem. Originally published in Bulgarian in 1967, the story follows Cem as he tries and fails to usurp his older brother at the behest of some of his countrymen. He is forced into years of exile that take him far from home, from Rhodes to France to Italy. His imprisonments—though those holding him would call it refuge—turn the almost-sultan into an unwilling pawn and bargaining tool for European powers, and eventually lead to his tragic downfall.

The Case of Cem is a daring blend of court intrigue, tragedy, and historical fact that masterfully captures complex layers of history in its prose and reads like an epic. Just as prevalently, though, it is a reflection on memory, identity, homeland, and what it means to lose them.

The narrative is presented through a series of court depositions, each one a testimony by someone involved in Cem’s story. These testimonies take place in an undated future, as each character is called forward to account for their role in Cem’s downfall. In this way, the narrative is designed to recall a forgotten history and to bring justice to Cem’s memory. Each first person testimony presents a tangible, unique speaker; from the haughty and self-righteous nature of Pierre d’Aubusson, to the quiet remorse of Cem’s erstwhile lover, Phillippe-Hélène, Mutafchieva and Rodel craft each voice with such depth that the reader feels as if they themself are in the courtroom.

The historical accuracy of these testimonies remains up for debate, but this doesn’t take away from their impact. Rodel observes in her translator’s note that Mutafchieva “clearly did not feel bound to one hundred percent historical accuracy in her fiction.” She changes names here, details there. Had she intended for this story to be a true-to-fact account, we would, of course, take issue with this decision. But for all its historical inspiration, The Case of Cem is a work of fiction. There is beauty in these unreliable narrators in that their omissions, hedges, and what may even be outright lies—for hardly anyone is entirely truthful in the face of their own wrongdoings—add layers of human complexity that are all the more compelling.

The most beautiful (and revealing) of these perspectives is that of the poet Saadi—Cem’s close servant and, as is made evident in Saadi’s testimonies, his lover. This queer representation is an impressive feat in and of itself, considering that the book was published under the watchful eye of Cold War-era censors. More impressive still is the artfulness with which Mutafchieva captures Saadi’s nearly unwavering devotion and love for Cem, as well as their gradual deterioration as the two become estranged. Rodel’s translation preserves these sentiments just as beautifully.

“I am looking for a way to save you from your doom. Because the sun would go out along with you…I want to be the stone beneath your feet, Cem, my friend, such that you tread on me on your way to salvation.”

The power in Saadi’s testimonies lies in the fact that they are so strikingly different from the preceding perspectives. Where most of the other speakers throughout the novel lay emphasis on their own roles in the conflict, Saadi dedicates his words to painting a picture of Cem himself—not only of his physical appearance, but of his actions and what Saadi believes to be his thoughts as well.

“I must admit that my eyes never feasted on another beauty such as Cem…Is there anything more captivating than a man, than a young man…who delights in his every movement, for whose springing step the world seems to have been created?”

Saadi’s depiction is the closest we get to a first-person account of Cem’s experience; Cem himself never gives testimony before the court. He is silent, an inanimate object in his own story, only moving when and where other powers will him. He laments at one point in his captivity, “I’m not saying I’ll die, my friend. But whatever happens from this point on will happen without me.” And so it does. For all intents and purposes, Cem remains in absentia. Our lack of access to his inner thoughts means it falls to Saadi, the one who “knew Cem better than he knew himself,” to be his voice.

So, it is Saadi who paints us the picture of Cem’s devastation after they are exiled from their homeland, to which most of the other narrators in the novel are oblivious or complicit. Saadi, on the other hand, is uniquely familiar with this grief, both because he, too, has been exiled, and because he must watch as this experience rips someone he loves limb from limb. Mufatchieva’s prose intimately captures this anguish and its accompanying internal conflict.

“I have suffered it out of empathy, that much is true. I was tied to a person with whom I shared the same thoughts, the same taste, and the same will; he no longer exists, that person. Am I obliged to serve a memory?”

In her translation, Rodel preserves the historical and cultural specifics of the story by leaving certain Turkish terms and titles untranslated. In contrast to this cultural positioning and the rich and grounded narrative voices, Mutafchieva and Rodel leave settings vague. We are told in which city the characters reside at any given time, but as Cem and Saadi are constantly and unwillingly moved farther and farther from their homeland, city blurs with city, prison with prison, until each setting becomes nothing more than a few stone walls.

Early on in the story, Saadi and Cem express wonder at the wide world, even though they are seeing it in exile. “There is something about the world,” Saadi says, “that makes it so precious—this is precisely what you perceive: its uniqueness. Your every meeting with some city, island, or shore is unique, and the wonderful thing is that you know that it will never happen again.” Perhaps it is exactly this idea—that every meeting with a person or a place could well be your last—that drives Saadi away from his lover, towards home again, in the end.

“Cem’s fate demonstrates that certain truths are not new,” writes Mutafchieva in the novel’s foreword. “For example, the fact that a complex dependency exists between a person and their homeland, one that has not yet been precisely defined.” This truth is demonstrated outright in the narrative, too—as Cem deteriorates, becoming an ugly, warped shell of the magnificent prince he once was, Saadi’s devotion slips. It was not only loyalty, but a lifeline to their homeland, that had kept the two together. As Cem faded, so too did the certainty that Cem would bring him home again. When Saadi finally attempts a journey home, years after their odyssey began, his perspective on the world has plainly and irrevocably changed:

“The world is not only large, I shall sing, it is also hostile. Hide away from it in a single homeland, a single city, a single home; fence off a small part of that big world so you can master it and warm it …cling to something amidst the boundless current of time, amidst the boundlessness of the universe. Choose one truth as your own.”

It is in this hostile world that Cem was left behind by those who had held him most dear, and where he was forgotten by the rest. In The Case of Cem, Mutafchieva captures all of the tragedy and humanity contained in a life long since passed. In calling forward those who loved him and those who used him, she asks them (and us) to bear witness to this prince, to their complicity, and to his memory.

Kathryn Raver is a writer and ESL teacher currently based in France. She also volunteers as an Assistant Managing Editor at Asymptote. She is the proud holder of a MA in Language & Cultural Diversity from King’s College London.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: