In our new column, Retellings, Asymptote presents essays on the translations of myths, those enduring stories that continue to transform and reincarnate. In this essay, Kanya Kanchana follows the whirling story of Śiva through dance, science, and myth.

“A life in which the gods are not invited is not worth living. It will be quieter, but there won’t be any stories.”

– Roberto Calasso,

The Marriage of Cadmus and Harmony

There was sound and the sound was colossal. From within the pulsing sound, from the heart of the creation and dissolution of the cosmos, a single beat could be heard—ḍam. Incantatory, the beat started to repeat—ḍam ḍam ḍam ḍam ḍam ḍam ḍam. The beat was coming from the ḍamaru, a small handheld drum. There was a god and he was dancing. He was Śiva and he shook all the worlds.

His matted locks flew wild. Gaṅgā, the holiest of rivers who was nestled in them, swelled in spate, tried in vain to keep him cool. The lambent crescent moon that adorned them, intoxicating soma, now glinted crazily. Vāsukī, the great serpent coiled around his blue, kālakūṭa-holding throat, reeled. Śiva’s locks were a forest (jaṭa, matted locks; aṭavī, forest, as the asura king Rāvaṇa sings).

Once upon a time, another forest: a forest of cedars (devadāru, wood of the gods, Cedrus deodara), into which Bhikṣāṭana Śiva, the mendicant, wanders naked, deep in despair for the sin of having killed Brahmā, his outheld palm an escutcheon, Brahmā’s skull still stuck to it somewhat like an alms bowl. The illustrious sages in the forest are not pleased to see this beautiful beggar who drives their women mad with desire. They send a tiger to shred him to bits; he flays the tiger and wears its bloody skin around his waist. They throw venomous serpents at him; he wraps them around himself as sinuous ornaments. They send a demon dwarf, the malign Muyalaka. Śiva steps on him and breaks his back. And then he dances. He dances until it dawns on them that he is none other than Śiva.

This story echoes in another story, in another forest down south: Chidambaram (cit, consciousness; ambaram, sky, space, also garment), a mangrove forest of tillai trees (Excoecaria agallocha) whose milky sap blinds upon contact. In such a time when the blinding trees grow wild, the sages who live among them grow drunk on their own power. They try to tame Śiva. And he dances again. Appar, the 7th century Tamil poet-saint sings:

If you could see

the arch of his brow

the budding smile

on lips red as the kovvai fruit

cool matted hair,

the milk-white ash on coral skin,

and the sweet golden foot raised up in dance,

then even human birth on this wide earth would be a thing worth having.

Sweet golden foot. This is not the sweet, throbbing, unbearable anguish of Kṛṣṇa’s rāsalīlā, nor the unvarnished joy of Gaṇapati’s ānanda nartana. This is Śiva’s dance.

Śiva, the lover, dancing his tender, hierogamous lāsya with Pārvatī.

Śiva Śūlapāṇī, the spear-bearer, dancing at twilight on the snow mountain Kailāsa, surrounded by all the gods, goddesses, and celestial beings in a divine choir.

Śiva Mahākāla, Great Time, the naked, ash-white ascetic, the first shaman, eyelids heavy from the smoke of his chillum, with serpents for garlands, with dogs for companions, churning up a mad, ecstatic froth on the charnel ground with the beautiful terror that is Kālī.

Also, Śiva dancing in victory after triumphing over sundry demons for good measure, with his faithful troops, his gaṇas, whooping about drunkenly.

But this is Śiva Naṭarāja, the cosmic dancer in the golden hall of Tillai, spontaneously dancing the universe into sṛṣṭi, creation, sthiti, preservation, saṃhāra, dissolution, tirobhāva, obscuration, anugraha, revelation. Rending the skies, lashing the stars, roiling oceans, tossing mountains—his pañcakriyā, five-fold activity—and still it is play. The one who sees the sweet golden foot is the one who does not look with otherly eyes.

Ādiśeṣa, the greatest of serpents, the one that remains (ādi, first, primordial; śeṣa, remnant) when all else is destroyed in the final dissolution, yearns to see the dance he has heard so much about from Viṣṇu. He assumes the form of Patañjali, the serpentine yogi, and goes down to Chidambaram with another sage Vyāghrapāda. Śiva Ādiyogi, the primordial yogi, dances in the thousand-pillared hall. “I am the originator, the god abiding in supreme bliss. I, the yogi, dance eternally,” says Śiva in the Kūrma Purāṇa (2.4.33). A thousand-petalled lotus blooms in Patañjali’s head. The tillai trees are only in stone on the temple walls now. But walk the vast halls, and you will see Śiva’s form in the bronze Naṭarāja, his abstract form in the crystal phallus, liṅga, and his formlessness as empty space behind the veil. Sound become movement become yoga. The dance is still on. Patañjali goes on to write the Sanskrit Yogasūtras in which he talks about the mind. He sees all the movements of the body, and yet his mind is on the mind.

There is, however, a later āsana called Naṭarājāsana, the posture of the King of Dancers. One leg is straight, the foot anchored to the earth. The other is lifted way back, and the arms go up and back down, bringing the foot up to touch the crown of the head. When I finally manage to do the full posture (years ago now), it shoots up a surge of energy. I never want to come out of the posture for fear I might never be able to repeat it. I repeat it but I never get the same one twice. Le Guin says in Dancing at the Edge of the World, “To make a new world you start with an old one, certainly. To find a world, maybe you have to have lost one. Maybe you have to be lost. The dance of renewal, the dance that made the world, was always danced here at the edge of things, on the brink, on the foggy coast.”

I also learn from my teacher a set of very old movement patterns that Bodhidharma is said to have carried over the Himalayas into China and introduced into Chan Buddhism, and further into Japan, where it formed the precursor patterns of Shaolin kungfu. The patterns, together called Śiva Naṭa, disintegrate me and then reconstitute me in practice. Creation of a pattern can only be subsequent and consequent to the destruction of an earlier one. They construct a maṇḍala around me, an energetic architecture in which I establish myself. The rhythms I intuitively choose for my music are from konnakkol, the South Indian art of rhythmic percussion, reminiscent of the ḍamaru. The ḍamaru in the South is onomatopoeically called uḍukkai in Tamil, uḍukku in Malayalam, and here the sound heard is ḍuk. Incantation has the same Latin root, incantare, as chant, as enchantment. “And all at once she understood what myth is, understood that myth is the precedent behind every action, its invisible, ever-present lining,” Calasso again.

Patañjali is not only a master of yoga, but also a grammarian in the tradition of the sage Pāṇini. Pāṇini, during his twelve-year-long tapas (fervour, ardour) to Śiva, hears the ḍamaru beat fourteen times. Fourteen classes of syllables drop, resonant, into his fervent ears.

a i u ṇ

ṛ ḷ k

e o ṅ

ai au c

ha ya va ra ṭ

la ṇ

ña ma ṅa ṇa na m

jha bha ñ

gha ḍha dha ṣ

ja ba ga ḍa da ś

kha pha cha ṭha tha ca ṭa ta v

ka pa y

śa ṣa sa r

ha l

Pāṇini turns on and tunes in, but does not drop out. He compiles the akṣarasamāmnāya, an ordered listing of phonemes, a foundational arrangement that will feed into his legendary Sanskrit grammar. Sound become syllable become grammar. There is a reason the sages are called seers, and not hearers.

Patañjali may not have cared too much about the physical postures, but not so the sage Bharata, who very much notices them. Śiva, a bit too busy for personal tutoring, instructs Taṇḍu to instruct Bharata on all the finer points—the 108 karaṇas, doings, coordinated movements of hands and feet; the 32 aṅgahāras, complex movements of limbs made up of karaṇas; the four recakas, the separate drawing up of limbs; and several other features. Bharata goes on to describe them all in Tāṇḍavalakṣaṇam, the fourth chapter of his performance arts treatise Nāṭyaśāstra, which then becomes a foundational text for actors and classical dancers, including the practitioners of the dance named after him, the Bharatanāṭyam. The movement patterns wrap around temple walls in Chidambaram, in Thanjavur, and elsewhere. The dance taught by Taṇḍu, tāṇḍava. Who is this Taṇḍu? He is none other than Nandi, Śiva’s stupendous bull.

Is tāṇḍava then just the one dance, albeit infinite and immeasurable? Sivaramamurti documents several in his monumental labour of love, Naṭarājā in Art, Thought and Literature, each performed at a special sabhā (cabai in Tamil), a hall, a court, an assembly, at a special location: Adrisabhā, the first stage on Kailāsa (adri, mountain) in the Tibetan Himalayas, homeground for Śiva; Ādicitsabhā, the hall of first consciousness, at Tiruveṅgāḍu, where he performs not one, but seven dances— ānandatāṇḍava, sandhyātāṇḍava, saṃhāratāṇḍava, tripurāntatāṇḍava, ūrdhvatāṇḍava, bhujaṅgatāṇḍava, lalitatāṇḍava; Ratnasabhā, ruby hall, at Tiruvālaṅgāḍu, where he performs the fearsome caṇḍatāṇḍava with Kālī; Rajatasabhā, silver hall, at Madurai, where he performs the beautiful sundaratāṇḍava; Citrasabhā, painted hall, at Kuttālam where he dances as Ardhanārīśvara, his body half male and half female; and the first among equals, Kanakasabhā, golden hall, at Chidambaram, where he dances the ānandatāṇḍava, the dance of bliss. It is telling that Chidambaram is the koil, the temple, that sabhā defaults to the golden hall. Chidambaram is the human heart.

There are many more halls where many more dances take place in endless fractals. Things are getting rather out of hand. We need a picture.

*

“A great motif in religion or art, any great symbol, becomes all things to all men; age after age it yields to men such treasure as they find in their own hearts. Whatever the origins of Shiva’s dance, it became in time the clearest image of the activity of God which any art or religion can boast of,” says Coomaraswamy in his 1918 essay, The Dance of Shiva, which brought this Indian image before the attention of the world, illustrating the story with extracts from several Tamil texts.

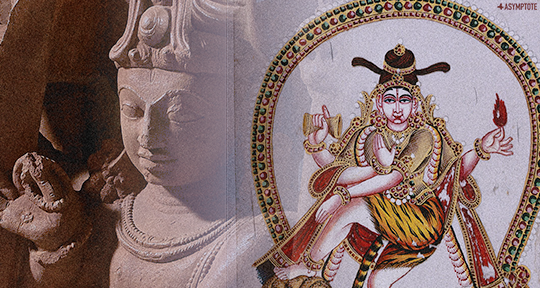

When we think of Śiva Naṭarāja, what he might look like, we are thinking of the incomparable late mediaeval Chola bronzes. Dehejia says of them in The Body Adorned, “a vision of divinity and sensuousness inextricably mingled.” Movement frozen, yet not static, in sculpture. Paśupati of the Indus Valley has come a long way, and as we discover, has lost none of his ithyphallic charm.

“To work magic, to put enchantments upon others, one has first to put enchantments on oneself,” says Zimmer in Myths and Symbols in Indian Art and Civilization. What do the bronzes show?

In a blazing full-body halo of fire, prabhāmaṇḍala, indicating the dance of nature, atop a lotus pedestal, stands the four-armed, minimally yet beautifully clothed, bejewelled Śiva, half his matted locks piled high upon his head like a crown and half whirling wildly about. Somewhere within the matted locks, Gaṅgā flows, a skull grins, a crescent moon illuminates, flowers of the entheogen datura (Datura metel) glow. A hooded serpent wraps around him, sways with him. In his top right hand, the ḍamaru, the instrument that causes the vibrations that cause all matter; in his top left, agni, the tongue of fire that causes transformation by destruction. The bottom right hand shows the abhayamudrā, the sign of fearless refuge; the bottom left crosses his torso to point elegantly to his own left foot lifted weightlessly in mokṣa, liberation. The right foot holds down firmly the demon of ignorance, Muyalaka. The prostrate demon is also known as Apasmāra (apa-, a prefix akin to mal-; smṛ, remembrance, memory): ignorance as forgetfulness, a kind of misremembrance of the true nature of things. Kramrisch calls him Amnesia in The Presence of Śiva.

Campbell records in The Ecstasy of Being, “an art that carries words to us from great distances.” Śiva’s face stays equanimous, serene, silent.

*

“In the night of Brahma, Nature is inert, and cannot dance till Shiva wills it: He rises from His rapture, and dancing sends through inert matter pulsing waves of awakening sound, and lo! matter also dances appearing as a glory round about Him. Dancing, He sustains its manifold phenomena. In the fulness of time, still dancing, he destroys all forms and names by fire and gives new rest. This is poetry; but none the less, science,” Coomaraswamy writes.

There has been a long line of physicists—Einstein, Bohr, Schrödinger, Heisenberg, Oppenheimer, and many others—who, regardless of whether they are confounded or outraged or intrigued or inspired by Indian intellectual traditions, engage with its philosophies, texts, and practitioners. But it is not until Capra’s much-lauded and much-criticised 1975 book The Tao of Physics that the door to such crossovers is unlocked in the popular imagination. When a door is open, all sorts of things tend to blow in, but I digress.

Calling creation myths across cultures a ‘tribute to human audacity’, Sagan, in 1980, goes on to say in Cosmos: “The most elegant and sublime of these [manifestations of gods sculpted in bronze] is a representation of the creation of the universe at the beginning of each cosmic cycle, a motif known as the cosmic dance of Shiva, […] these profound and lovely images are, I like to imagine, a kind of premonition of modern astronomical ideas. If there is more matter than we can see—hidden away in black holes, say, or in hot but invisible gas between the galaxies—then the universe will hold together gravitationally and partake of a very Indian succession of cycles, expansion followed by contraction, universe upon universe, Cosmos without end. If we live in such an oscillating universe, then the Big Bang is not the creation of the Cosmos but merely the end of the previous cycle, the destruction of the last incarnation of the Cosmos.”

There is no such thing as a pure creation myth, of course. Any good creation myth holds within itself the spark of destruction. And no good destruction myth is without the seed of creation inside. Quite like the yin–yang symbol, where the white oceanic swirl has a luminous black dot within, and the black, a white.

CERN, the European Organization for Nuclear Research in Switzerland, home of the Large Hadron Collider, the world’s largest and most powerful particle accelerator, has hosted a towering two-metre statue of Śiva Naṭarāja for over eighteen years. I come across a note by a CERN postdoc: “So in the light of day, when CERN is teeming with life, Shiva seems playful, reminding us that the universe is constantly shaking things up, remaking itself and is never static. But by night, when we have more time to contemplate the deeper questions, Shiva literally casts a long shadow over our work, a bit like the shadows on Plato’s cave. Shiva reminds me that we still don’t know the answer to one of the biggest questions presented by the universe, and that every time we collide the beams we must take the cosmic balance sheet into account.” Or as Huxley puts it more succinctly in Island, “rub-a-dub-dub—the creation tattoo, the cosmic reveille.”

In 1993, a one-kilo aluminium sculpture called the Cosmic Dancer is launched from Baikonur Cosmodrome in Kazakhstan and ‘installed’ at the Russian Mir space station. Weightless in more than one way, this geometric artwork spins freely. Cosmonauts dance with it. They plan to send a 2.0 in 2020 but Covid strikes. And now, the war. I wonder what is happening with the new sculpture.

*

When we are done with the usual tedious businesses of myth vs reality, myth vs historicity, myth vs authenticity, myth as faith, myth as illusion, myth as falsehood, myth as metaphor (close but not quite), etc. (such discussions, perhaps necessary, perhaps not, are meant for a different sort of café serving more prosaic drinks), we might get down to the task at hand.

Here we have a mythopoeic myth whose genesis is, in itself, an ambitious act of translation. Sound become movement become yoga become pattern become grammar become language become story. Śiva moves in dance, in sculpture, in painting, in poetry, in ritual, in physics. He moves bodies living and dead. And still he is not done. What are we to do? Do we watch; do we take notes; do we dance?

*

We no longer eat; we consume food. We no longer read books; we consume content. We no longer listen to music or watch films; we consume media. We are no longer artists and aesthetes (sahṛdaya, those ‘possessed of heart’); we have allowed ourselves to be redefined solely as producers and consumers in the global marketplace, and what’s more, started to take pride in this vocabulary of production and consumption.

Myths, too, have not escaped this turn. We produce them. We consume them. We see them through eyes inflamed by our own agenda, parse them to our own urgent preoccupations. Overwhelmed, we flatten their layers, dull their nuances, correct and homogenise our responses to them. We coopt their simulacra to tell our unending trauma memoirs. We appropriate their words until they mean almost nothing—ages, aeons, ritual, journey, storytelling, epic, iconic, fantastic, great, awesome! We mine them for obscure artifacts—talismans and totems. We claim to “work with the available material,” as Lenin said someplace.

Obsessed, desperate to have a hand in something that feels close to the marrow, we endlessly remake them in our own image, reimagining, retelling, running out of re–s, until realising that all myths are acts of translation echoing multiply, tracing a variform path through space and time, mind and word—one way or another. While a case may be made for the modern human instinct for intervention and curation as an outcome of the original (and useful) civilising instinct, we are pulling flowers off branches and arranging them, already dead, in pretty vases. We must look at the whole bloody tree. What do we wish to bring into being? What do we wish to hold close? What will go with us the distance?

The 12th century poet Akkā Mahādevī calls Śiva Cannamallikārjuna, beautiful lord, bright as jasmine. A jasmine-bright myth yesterday is still a jasmine on the bed the morning after—a little crushed, a little worse for the wear perhaps, indoles rising in the scent, but holding all the staggering knowledge, all the incandescent beauty of the world in itself, gathered in a single, winding, heartbreaking night. We begin again.

Kanya Kanchana is a poet from India. Her work has appeared in POETRY, Asymptote, The Common, Anmly, and elsewhere. It has also been indexed at The Columbia Granger’s World of Poetry, shortlisted for the Disquiet Prize, nominated for The Orison Books Anthology, and remixed and performed to music. Her translations have appeared in Asymptote, Exchanges, Waxwing, Circumference, Aldus, and Muse India.

Kanya is also engaged in practice, teaching, nonprofit work, and philological research at the intersection of tantra and yoga. She has a Research MPhil in Sanskrit Studies from the University of Cambridge.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: