In our new column, Retellings, Asymptote presents essays on the translations of myths, those enduring stories that continue to transform and reincarnate. In this essay, Claire Jacobson covers the path of the Seyavash cycle through time and cultures, its adoptions and adaptations.

In Khurasani poet Abu al-Qasim Ferdowsi’s epic the Shahnameh, symbol of innocence and hero-prince Seyavash undergoes a false rape accusation, a martyr’s death, and a symbolic resurrection. This tale—the pure hero is falsely accused of rape and suffers either a literal or symbolic death and resurrection as a result—is found across cultures and time, often beginning with the hero’s virtuous rejection of a lustful woman: the incorrupt Seyavash recoils from his stepmother Sudabeh’s declarations of love, as does the Khotanese version of the Mauryan prince Kunala from Queen Tishyaraksha; the righteous Joseph (Yusuf) flees Potiphar’s wife, Zulaikha; the chaste Hippolytus rejects Phaedra’s advances; the honorable Bata refuses to betray his brother Anpu by sleeping with his sister-in-law. Much like Seyavash, each of these men are then written into the cycle of accusation, death, and resurrection.

Many of these myths coexisted in a shared discursive space, but not all of them continued to develop and change as living stories. After the Islamic conquest of the Iranian plateau, several began to converge. By the early Islamic period, the tale of Yusuf and Zulaikha was considered by literary critics to be the same story as Seyavash and Sudabeh but in a more appropriately Islamic format, and many of the rituals that had long been practiced to celebrate Seyavash were repurposed to commemorate the death of Husayn at Karbala. In this case, ritual (by which I mean the popular practice of religion) seems to act as a medium of translation, carrying the shape of the re-enacted story forward even though the language, notions of gender, and cultural landscape were all slowly changing as the millennia passed.

Like many of these stories, the tale of Seyavash is actually a cycle containing several smaller narratives. The son of Iranian king Kay Kavus by a concubine, Seyavash is raised by the legendary hero Rostam. When he grows up, he goes to visit Kay Kavus, and his father’s wife Sudabeh immediately falls in love with him. When he rejects her advances, she fakes a miscarriage, accusing Seyavash of rape. Seyavash must pass through a literal trial by fire to prove his innocence:

… Seyavash replied,

“No need to grieve that Fate has turned out thus.

This infamy fills all my mind and if

I’m innocent, the trial will rescue me.

And if I’m guilty of this sin, then God

Will not protect me now. But by the power

Of God who gives all benefits, I’ll feel

No heat at all from this huge hill of fire.”…

Then Seyavash, unhesitating, turned

Towards the fire and urged his black horse forward

From each side tongues of flame leapt out, his horse

And helmet disappeared, and on the plain

The crowd’s eyes strained through desperate tears to see

If he would ride out from the blaze. Then they

Caught sight of him and what a shout went up—

“The young prince has escaped the flames!”(Ferdowsi, tr. Davis, 1.898-905, 915-922)

A pattern of virtue followed by false accusation continues throughout the story. Later, though he is victorious on a battlefield, Kay Kavus demands that Seyavash kill hostages, break a peace treaty, and pursue further war with a kingdom he has just defeated. Disgusted with these orders, Seyavash refuses and goes into exile in Turan. He does very well in his new home and gains the favor of the Turanian emperor Afrasiyab, even marrying his daughter, which arouses the jealousy of others in the court. They falsely accuse him of treason, and the emperor executes him unjustly. But, on the spot where his blood strikes the ground, a tree begins to grow:

…Then in that ruined city

The soil began to flower, the weeds became

Tall cypresses, and from the dust that drank

The blood of Seyavash a tree rose up

To touch the clouds; each leaf displayed his likeness,

And from his love there came the scent of musk.

It was an evergreen that flourished in

December’s cold as freshly as in springtime.

A place where those who mourned for Seyavash

Would gather and bewail his death and worship.(11.266-275)

Ferdowsi seems to have added the Seyavash cycle to the Shahnameh in 387AH/997CE, a few years after he had already completed the first version of the poem. Though the Shahnameh contains easily the most well-known version of the Seyavash cycle, it is not the only one, nor is it the oldest. Seyavash appears to have originated long before the Common Era in the Eastern Iranian oral tradition from Greater Khurasan, though it would have spread to the west along with Iranian imperial dominance. We have fragmentary textual references to him as a literary character, historical and mythical figure, and deity from Sogdia, Bactria, Margiana, and Khwarazm, as well as probable traces in the Parthian oral tradition.

However, before the Sassanian urge to collect these oral stories resulted in the Xwaday-namag, a fifth century prose text upon which Ferdowsi heavily relied, there does not appear to have been a codified Seyavash narrative on which all these societies agreed. The Seyavash-in-Iran stories appear to be quite distinct from the Seyavash-in-Turan stories, and the written narrative may have been an attempt to harmonize different traditions. What was agreed was that he dies a martyr’s death at the hands of Afrasiyab (the mythical king of Turan, known as one who holds back the rain), that his death results in new life somehow, and that one was to commemorate his death each year, usually at Nowruz and often through various kinds of mimetic rituals. These elements seem to indicate that early on, Seyavash was some kind of nature deity whose death and resurrection were tied to the new year and to the cycle of droughts and rains on the Iranian plateau. He was only taken up as a mythical and literary character in later times, and as often happens, each storyteller added new layers to the telling.

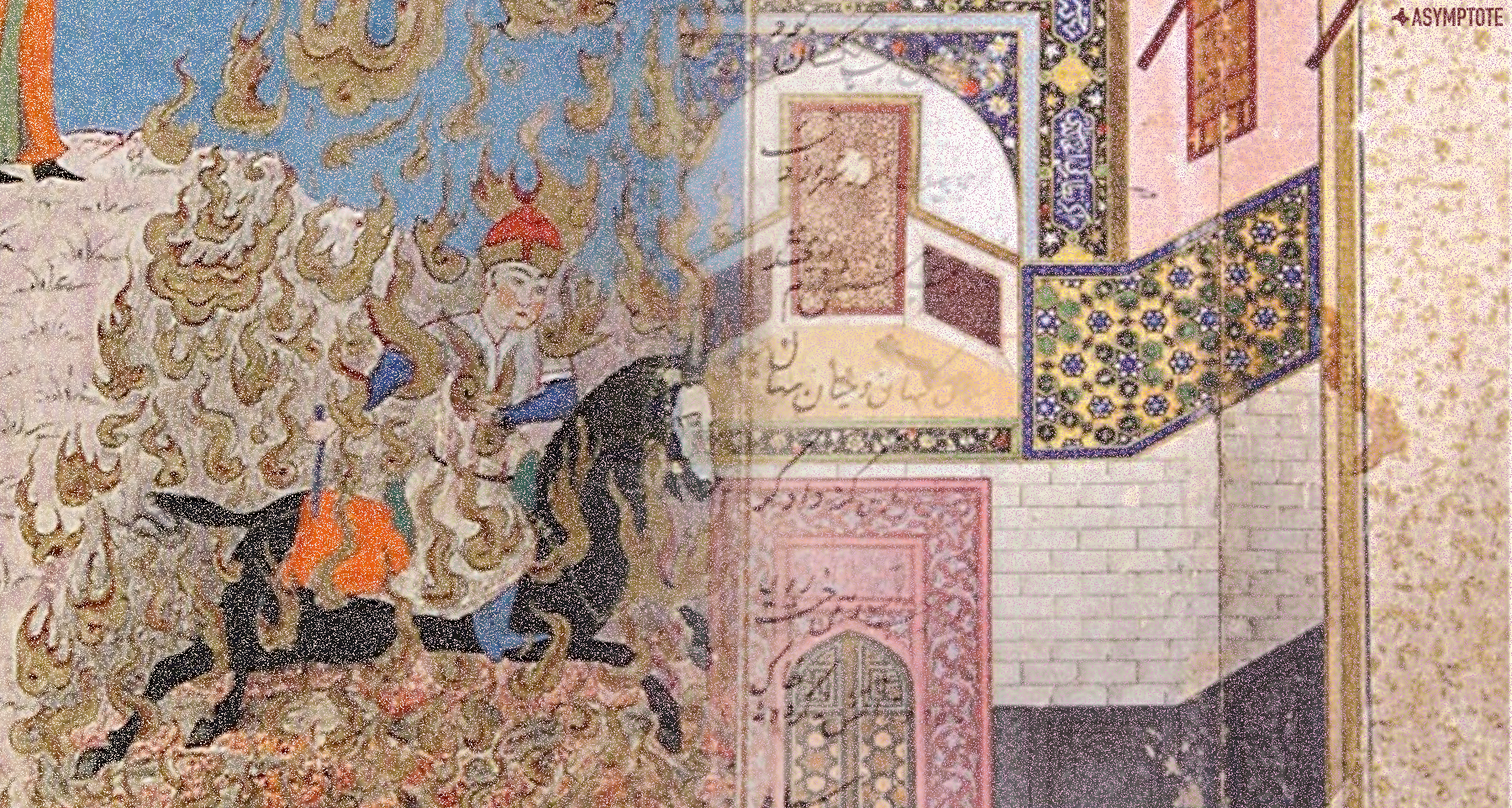

As with many nature or fertility cults, the death of Seyavash was commemorated because it is not simply a death, but rather a death for a purpose, a death for the good of creation. Seyavash is mourned as part of an early redemptive suffering tradition, the commemoration of which took on a participatory form in many different societies. Worshippers offered blood sacrifices at cultic sites, reenacted the myths, sang specific songs known as “Revenge for Seyavash,” and ritually mourned, which often included self-flagellation or (like the cult of Hippolytus at Troezen) the cutting of hair, as seen in the image below. Notably, similar cyclical mourning rituals once took place in Sumer for Dumuzid, the nature god and shepherd-husband of Inanna who took her place in the Underworld, and the two cults were doubtless connected.

Mourning Scene. Wall painting, 6th century CE [Panjikent, Tajikistan]. St. Petersburg: The State Hermitage Museum. Retrieved from https://sogdians.si.edu/mourning-scene/ A Sogdian mural depicting a ritual of mourning for a young man, generally believed to be Seyavash. A woman some scholars believe to be the goddess Anahita is also shown. The gradual conflation of Anahita’s cult with Inanna’s has been established; Richard Foltz argues that images like this are evidence of Mesopotamian influence on the early Seyavash-Dumuzid nature cult.

These reenactments, poems, and songs are, broadly speaking, referred to as Seyavash-khani.

The Seyavash cycle and Seyavash-khani are reflected in other legendary stories of martyrdom and resurrection, like that of Husayn b. ‘Ali. Like the other heroic figures referenced, Husayn is remembered as remarkably virtuous; in stories, he is said to physically resemble his grandfather, the Prophet Muhammad, and he is also said to possess great knowledge, wisdom, compassion, and piety. He reportedly foretold his own martyrdom as a child, a fact which is meant to portray him as someone with access to divine foreknowledge, who is submissive to God’s will, and who is incredibly courageous. Prominent Shi’a jurist Ibn Shahrashub reports that Husayn said, “God made fasting obligatory in order that the rich may feel the pain of hunger, and thus share their wealth more generously with the poor,” and his reputation is characterized by karam or generosity, hospitality, and magnanimity towards his own household and towards strangers.

His martyrdom, like that of Seyavash, came at the hands of an unjust ruler who felt threatened by his popularity. When the Umayyad caliph Yazid demanded Husayn’s allegiance, he refused. As head of the influential Banu Hashim and representative of the Prophet’s family, Husayn posed both a political and religious threat to Yazid’s authority, and rather than submit to impious leadership, he decided to oppose Yazid publicly. During his journey to Kufa, the seat of his father ‘Ali’s caliphate and the base of the opposition to Umayyad rule, the newly appointed Sufyanid governor of Kufa and Basra ‘Ubaydallah b. Ziyad cracked down on his supporters and the opposition crumbled. This left Husayn high and dry with between forty and one hundred followers in the desert. ‘Ubaydallah sent ‘Umar b. Sa’d with four thousand soldiers to confront him. Shi’a sources recount the subsequent battle as full of dramatic confrontations, pauses to recite poetry and make speeches, miraculous occurrences, and prophetic statements. Ultimately, after a day of battle, Husayn was killed, his head cut off and taken to Yazid. (Some scholars, less inclined perhaps to give credit to the hagiographic sources, tend to think Karbala was more of a massacre than a battle.)

The famous ‘Abbasid-era traditionist al-Tabari tends to filter out the most extreme of the supernatural reports—the sky does not rain blood in his Tarikh al-rasul wa al-muluk (History of prophets and kings) like it does in other maqatil writings, such as the reports collected by Ibn Shahrashub. But, even al-Tabari records miracles done by Husayn on the day of his death, curses he called down on those who participated in the killing, and moving speeches from the middle of the battlefield in the midst of the fighting. Somehow, the story of Husayn’s martyrdom was embellished to include the above elements and others, such as his blood performing acts of healing; animals bearing witness to his martyrdom; some of his murderers repenting instantly (cf. Seyavash); and onlookers catching sight of his severed head and converting on the spot. An unorthodox belief even among the Shi’a, but still widespread, was that Imam Husayn did not die, but was taken up to heaven—reminiscent of the occultation of Seyavash’s son Kay Khosrow (much more mainstream is the belief in the occultation of his descendant, Muhammad b. Hasan al-Mahdi). Partly because of who he was and partly because of what he represented, the death of Husayn could never have been just a death. It was always going to mean more.

The response to Husayn’s martyrdom, like that of Seyavash, was one of ritual mourning (including a rich poetic tradition), participatory suffering (including both mimetic and self-flagellation elements), and symbolic calls for revenge against his enemies. The resemblance to Seyavash-khani has been noted by a number of scholars of Iranian history and religion, including Beeman (2011), Chelkowski (2009), and Malekpour (2004). Ibn Qulawayh records an early ziyarah liturgy that says, “Through you [the imams] God takes revenge for the blood of every believer that must be exacted. Through you the earth brings forth its trees, and trees bear their fruits. Through you the sky sends down its rain and sustenance. Through you God takes away all sorrow,” a pattern of imagery evidently influenced by the Zoroastrian discursive space that produced it. Sogdian mourning rites included weeping, lamenting, and self-flagellation, which will be recognizable to anyone passingly familiar with ‘Ashura and the commemoration of Karbala.

Ta’ziya, or the passion play, combines many of these poetic elements and staged reenactments of events. The early Shi’a were first permitted to publicly observe ‘Ashura in Baghdad in 351 AH/963 CE, ruled by Sunnis under Buyid pro-Shi’a influence, which means these existing practices had previously been carried out privately or under threat. The report from that year describes public lamentation, pitching tents that represent Husayn’s camp, and a processional in which participants beg for water, all of which remain part of ‘Ashura rituals today. A key element of ta’ziya is that it is participatory; the procession includes reenactments that involve everyone, not just the main performers, and performances often include chorus-like call-and-response elements. The passion play developed from the early participatory processionals to a fully-developed theatrical production in the Safavid era.

The various retellings of the Seyavash cycle and the Seyavash-khani were heavily influenced by Islamization. Islamization refers to two separate processes: the spread of political control by Islamic powers, and the spread of Islam as a religion to the masses. Although the former was a relatively quick process, the latter took place over many centuries. Contrary to popular belief, the adoption of Islam by conquered populations was discouraged at first due to the financial benefits to the government of levying the jizya (and for a long time Islam was considered to be the property of the Arabs, meaning that sometimes even when conversions occurred, no financial benefits accrued). As a result, large portions of the population remained Zoroastrian for the first few centuries after Islam arrived. It wasn’t until the Safavids came to power that people had an interest in deliberately transforming these ancient rituals into a more recognizably Islamic practice.

Iranian Shi’ism was first imposed as part of a system of top-down reforms meant to invent Persia as a unified ideal in opposition to its Sunni Ottoman enemy. The Shahnameh was incorporated into this new Persian identity, with Shah Ismail embodying the mythical Rostam and Kay Khosrow as the hero and wise ruler, but that identity was at the same time intended to be distinctively Shi’a. Under Safavid rule, non-Shi’a religious communities (Sunnis, Jews, Armenian and Georgian Christians, Hindus, and Zoroastrians) were subject to various forms of persecution, including forced conversion. The development of ta’ziya and other forms of theater as a genre dates from this period; ta’ziya is arguably an attempt to adapt the existing ritual of mimetic participation in redemptive suffering to Husayn. Omar Koshan, the ritual burning of ‘Umar b. al-Khattab (or possibly ‘Umar b. Sa’d) in effigy, fits neatly into the symbolic revenge tradition that dates from the pre-Islamic period.

The shape of the story of Seyavash served a useful communal and religious purpose, so it proved worth preserving in its Islamicized form. Sara Ahmed famously called affect “sticky,” that is to say, it binds people to objects, spaces, and to other people, forming social ties which are intentional and directional. People who possess a “shared orientation” towards the same things as good constitute a social group. Ritual, or religious practice, functions in a community by orienting people to the same ends and strengthening social bonds, and group membership is self-perpetuating in that while the individual is affected by the group, other group members are likewise affected by that individual. Participation in mourning rituals is a way that social bonds form through shared affect, in this case sorrow or distress and guilt. Bodily participation in reenactments and theater performances, for instance, can play this role, and have done so since before they were Islamic, drawing a physical connection between the Seyavash-khani and the ta’ziya of Husayn. If the rituals as such are the bridge from one story to the other, we can view this transformation as an act of translation. As long as the rituals themselves continue to exist and perform the same function of shared affect, whether they are “authentically” Islamic or something else is beside the point.

But, what about Seyavash’s father’s wife Sudabeh and her terrible accusations? How would the Islamic world handle her? As mentioned above, the Qur’anic tale of Yusuf and Zulaikha quickly became associated with that of Seyavash and Sudabeh, but continued to evolve and take on new meanings. Zulaikha has, at different times and in different places, been read as a wicked temptress, an adulteress, a helpless victim of Yusuf’s great beauty, or a great lover of God in the Sufi sense of the word. The final interpretation of Zulaikha may be unorthodox, but it reflects popular religious practices and beliefs that didn’t always align with institutional values. Tenth century Sufi theologian al-Qushayri used Zulaikha as an illustration of the constant human striving against the lower self, painting her as a tragic victim of her own desires but ultimately redeemable, perhaps trying to bridge the moral gap between the written text and an oral tradition that had a repentant Zulaikha eventually marrying Yusuf.

Later Persian and South Asian poets such as Jami, Shah Muhammad Sagir, and Hafiz Barkhudar went even further, arguing that Zulaikha should be forgiven because her love of Yusuf was a representation of her love for God. This interpretation aligns neatly with the Sufism of Ibn ‘Arabi and Mansur Hallaj, for whom divine love could be expressed in earthly (and often carnal) ways. This treatment of the tale elevates Zulaikha to almost prophetic status as she endures a long and difficult tariqa (spiritual journey), overcoming moral and physical obstacles on her way to achieve union with the Beloved.

Her role has unmistakable parallels with that of Aseneth in Joseph and Aseneth; in the ancient romance, Aseneth must renounce her idolatry and repent before she can marry Joseph, and has a transformative angelic encounter in which she eats a honeycomb from heaven, thus receiving divine knowledge and undergoing physical transformation. These parallel traditions place Joseph/Yusuf in a prophetic position beside a woman who must go on a spiritual journey before earning the right to be his wife, providing inspiration to the garden-variety believer who struggles in their daily life and needs a more relatable figure to look up to than an infallible prophet. Interestingly, Sudabeh never receives the same rehabilitation as Zulaikha did in the Sufi tradition, remaining by all accounts a scheming and sexually transgressive temptress. Though perhaps, due to her almost complete identification with Zulaikha in Persian art and poetry by the time of Ferdowsi, she doesn’t need it.

In the ancient world, a story existed in which a handsome and virtuous man is accosted by a woman with whom he has a family-like relationship in an attempted seduction. When he refuses to bend his principles, she accuses him of rape, and in spite of his proven innocence, the man undergoes trials and suffering, sometimes even death and resurrection or reincarnation. People recognized the shape of this story and retold it all over the world, though the details changed in predictable ways, localizing the characters and integrating them into or harmonizing them with local cultic practices.

The two major episodes of the Seyavash cycle were translated into the Islamic mythos in late antiquity; we know that Yusuf and Zulaikha, as parallel figures to Seyavash and Sudabeh, Islamicized the tale and bridged the gap between a foreign religion and local traditions. It’s also clear that after the death of Husayn, Iranians recognized a virtuous hero of mythological proportions and borrowed from a familiar idiom to mourn his martyrdom.

These episodes found new life in their Islamic analogues, and Iranians kept hold of their ancient stories under new names. Practices concerning Seyavash are documented among several pre-Islamic Iranian societies, where ritual self-flagellation and mimetic participation in his suffering were supplemented by mourning songs and symbolic revenge. All four of these elements are also found in the commemoration of the martyrdom of Husayn, suggesting that either the rituals arising around Husayn’s martyrdom were borrowed from an existing repertoire, or that the pre-Islamic rituals that bound these communities together carried the shape of the story forward into a new era, or possibly a little bit of both.

Claire Jacobson is a doctoral student in Middle Eastern Languages and Cultures at Indiana University Bloomington and a middle school substitute teacher.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: