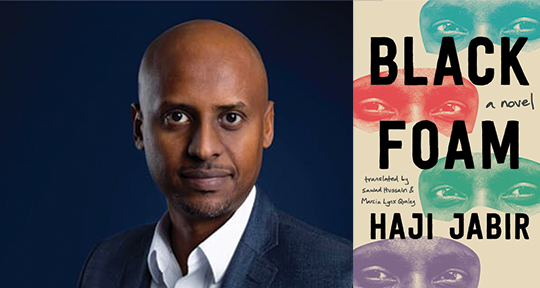

Black Foam by Haji Jabir, translated from the Arabic by Sawad Hussain and Marcia Lynx Qualey, Amazon Crossing, 2023

In a 2019 interview with Marcia Lynx Qualey for Arab Lit, Haji Jabir gives a fascinating response when asked whether he writes “political novels”: “I write about the people of my country, because they are a persecuted and suffering people, and so my novels come in this manner. I would like to write far from politics, but I would betray these people if I turned away from their issues.” At the time of the interview, Jabir had recently published (رغوة سوداء (2018), which has now been jointly translated into English as Black Foam by Sawad Hussain and Qualey. The novel follows an Eritrean man on a journey to find his place in the world, and as he uneasily moves from one location to the next, unable to find a place where he can lay down roots, he changes names and identities fluidly in order to fit in, to have a better chance at a new life.

Given the name Adal at birth (or so he says), he claims to be a ‘Free Gadli’, the Eritrean term for children “born of a relationship between soldiers on the battlefield that goes against religious law.” The Eritrean War for Independence against Ethiopia went on from 1961 to 1991 and Adal, by his admission, was born during this conflict, growing into a seventeen-year-old soldier when Eritrea was finally liberated. To avoid the association with “Free Gadli” in the post-war nation, he changes his name to Dawoud. He is then sent to the Blue Valley prison camp for infarctions committed when he is supposed to be in the Revolution School, but when he supposedly escapes—though he never divulges how—to the Endabaguna refugee camp in Northern Ethiopia, he becomes David. From there, he manages to enter the Gondar camp by posing as a Falash Mura named Dawit, and gets resettled in Israel. These changing names indicate transformation by association, from a Muslim to a Christian to a Jew.

In inscribing his protagonist with an ever-shifting self, Jabir asserts that stories are a potent tool for self-fashioning; they dictate affiliations and guide assimilations, helping Adal become whoever he needs to be at that very moment. The oral traditions of storytelling are further reflected in the way the novel is structured. The narrative is circuitous and fluid, the chapters quickly moving between the past and present in order to flesh out details, with the name Adal uses as the quickest identifier of time and place. In Jerusalem, during an interview with a sociologist, he is asked which of his three names he prefers: “Should he say Dawoud, with all the defeats and losses that old name carried? Or should he choose David, a newer name, yet with as many bitter experiences? Or should he stick with the infant Dawit, without knowing for sure whether it was any different from its predecessors?” Seemingly a simple question, it clearly throws him into existential confusion.

Understandably, this repeated switching has put his identity into flux, and the names become perfunctory identifiers rather than something that is a natural extension of him. Instead of propping him up, they bring him down: “He couldn’t get rid of these names and everything they carried. Each one was a weight that dragged behind him, like a cupboard of memories, and he couldn’t seem to pass by any bit of anguish without storing it inside them… These names which he had wanted to save him had instead become a burden… Names were just rags after all; they couldn’t hide his fate.” The names are both salvation and a trap; they quickly outlive their use whenever the protagonist is forced to go on the run again, towing around each new moniker with a fresh identity that does not, in any way, guarantee him peace of mind or an end to his long journey.

The reader is not really in a privileged position when it comes to knowing the actual truth. Adal/Dawoud/David/Dawit is always creating stories, layers upon layers, and it is not possible to correctly separate the wheat from the chaff. Given the nature of stories, even Adal can become quite lost in them: “Storytelling was a dangerous game, and the tale could slip from your hands at just the moment you thought it was fully yours.” When the tale slips away, it is time to move on. For the longest time, one is led to believe that the story he tells a man from the UN, about Aisha in Asmara, is actually true, but towards the end of the novel, he admits that he fabricated most of it. What is real then, and what is imaginary? Only the present action seems trustworthy since the narrative is told in the third person, without Adal’s voice infiltrating and altering reality.

In an incident early in the book (but later in the timeline of events), it is revealed that stories help the listless Adal cope: “That was how he dealt with things—turning everything around him into an exciting story. He could even come back to them dozens of times. He rearranged events, added to them, shucked off their husks and appendages, moving in toward the body. The story would start out strong, then slow down before rising up again and taking his listeners’ breath away.” Later in the book (but in an earlier event), however, when his resettlement bid is rejected, Adal-as-David suffers the consequences of fiction: “Now, David felt the grief of a tale brought to life by its teller in such a way that its dimensions disappear, and it dissolves and vanishes so that he no longer knows whether this tale was something that came from him or whether it was an invading body that came in and went, leaving him behind.”

Similar to the non-linear narrative, Jabir brings motifs circling back to re-emerge. When Adal’s “real” identity is discovered in Jerusalem, forcing him to go into hiding, his saviour is a Palestinian man to whom he gives the name “Dawoud”: “Here he was, going back to the first name he’d chosen, as if he had gone full circle, yet without reaching his final destination. How many circles would destiny take him through before he reached the end of all these exhausting turns?” These circles, however, are of his own making: stories he spun out in order to grasp the world. He is also at their mercy: “Stories have one door through which we can enter, after which we spin in their world forever. No matter what we think, there’s no escape from the stories in which we have become entangled.”

Another recurrent motif that hinges on orality is that of music, specifically in the form of communal singing. In the opening scene, a chosen few—including Adal-as-Dawit—are going to the airport on their journey to Israel, and the group spontaneously starts singing to celebrate their forthcoming salvation. Once the plane lands in Tel Aviv, the passengers once again break out in song as they all impatiently wait to de-board. It is a phenomenon that repeats itself when they are being taken around Tel Aviv, and a common occurrence at the Gondar refugee camp as well. As his benefactor, Saba, remarks: “You must have noticed that the people here survive by singing. They sing when they grieve, they sing when they’re happy, and they sing when they’ve got nothing better to do… To them, singing is their mother tongue… [It] takes their souls back to [the Promised Land] before their bodies can actually reach it.”

In the last chapter, Haji Jabir dedicates the book to “the memory of the young Eritrean Habtom Ouldi Mikael Zaroun.” Although not much information can be found on this individual, the last chapter makes it seem that he is the inspiration for Adal. In the aforementioned interview, Jabir identified his overarching literary project as “namely, shedding light on Eritrea and the Horn of Africa, on its people, history, and culture.” Black Foam attends to the violent past of the Falash Mura—the descendants of Beta Israel (a historical Jewish community in Ethiopia) who had converted to Christianity to escape persecution. While most have now immigrated to Israel and converted, they continue to be marginalised on the basis of race and the newness of their faith. Jabir says: “In Eritrea, we are still living outside history, enslaved to an oppressive regime in various forms, and all of this is considered the meaning of ‘homeland,’ which is innocent.” Black Foam speaks powerfully to this layered subjugation.

Towards the middle of the novel, Dawit is struck by a thought: “From Asmara to Endabaguna to Tel Aviv, and now to Jerusalem. All of these places had tossed him to the surface, like foam, without allowing him into their depths.” He has remained outside instead of becoming a part of things, and his relationships with these places are inevitably superficial as he uses crime and subterfuge to move from one to the next. Eventually, he is resigned: “He was getting used to it, even accepting it. He was embracing the idea of black foam now and no longer trying to get past it. Let the surface be his place—what of it?” In the end, Adal is left uncertain of his identity, his religion, and his nationality. His efforts leading up to this instant had been in a bid to find a place to belong, the promise of a home, but all he has encountered is hostility. Israel is ultimately closed to him, just like Eritrea and Ethiopia. His lifelong search is destined to remain unfulfilled.

Areeb Ahmad is editor-at-large for India at Asymptote and books editor at Inklette Magazine. Most of Areeb’s writing can be found in his bookstagram, a true labour of love. His reviews and essays have appeared in Scroll.in, Gaysi, The Chakkar, Mountain Ink, and elsewhere.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: