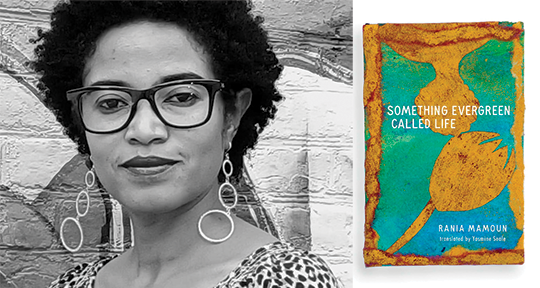

Something Evergreen Called Life by Rania Mamoun, translated from the Arabic by Yasmine Seale, Action Books, 2023

An outspoken activist against the regime of Omar al-Bashir, Rania Mamoun was forced to flee her homeland of Sudan in 2020 and seek asylum in the United States with her two small children. As a cloud of fear and uncertainty cloaked the globe, asylum turned to exile; COVID-19 rendered everywhere unsafe. Written against this backdrop of extraordinary circumstances, Something Evergreen Called Life is Mamoun’s first collection of poetry. The result of a hundred-day commitment between the artist and her friend as they sought direction and companionship during the most isolated phase of the pandemic, she credits her daily practice of putting verse to feeling for her survival and restoration. Mamoun is the author of two novels in Arabic, Green Flash (2006) and Son of the Sun (2013), as well as Thirteen Months of Sunrise (2019), a collection of short stories translated into the English by Elisabeth Jaquette and shortlisted for the Warwick Prize for Women in Translation in 2020. Her contribution to Banthology: Stories from Unwanted Nations (2018), was formerly reviewed in Asymptote.

Something Evergreen Called Life is a collection of free verse. While organized chronologically, with a day or two passing in between each poem, there is no illusion of exposition. Like innermost thoughts, the poems interject themselves, exemplifying the lack of introduction or transition in our most private ponderings. As a result, we read Mamoun’s poems like the revelations of a close confidant; because she writes without shame, there can be no judgment. It is in this unrelenting vulnerability that Something Evergreen Called Life finds its power.

At its core, Something Evergreen Called Life reflects the ebbs and flows of Mamoun’s deep depression:

the water goes over me

I am drowning

without getting wet

grasping the hem of survival

struggling for breath

And anchors Mamoun—‘a stray cat circling / her bearings lost’—in the ordinary moments of daily life in exceptional times. The streets she looks onto are both lonely and hopeful, and the events taking place within her walls, such as her daughter’s birthday, joyful and dystopic:

Raghad came out

they sang her happy

birthday we stood

in scattered blue

circles on tarmac

our bodies apart

Such dissonances are also to be found in the poems’ recollections, with fond snapshots of her mother standing in stark contrast to the brutalities of her days of dissidence in Sudan:

martyr

follows martyr

as the world watches

souls hover

The collection as a whole, therefore, reads like a release of not only the suffocating circumstances of its time, but of embedded wrongs born and buried, then reemerging unwieldy. The reader is a witness to a process of reckoning and healing, as Mamoun’s memories of unmentionable burdens break through and come to the fore, as in a poem on the domestic violence pervasive in her homeland:

in my country

they beat sisters wives daughters

in the name of religion discipline honor

hitting women is man’s honor

And a description of her circumcision, a confounding betrayal:

they bridled my desire

& since the age of five I live

a permanently stifled life

Markedly, the poetry which grapples with the systemic and systematic are not given greater weight than the solitary struggles to which we all relate. Each poem is a day in and of itself. Ruminations on injustice give way to a study on isolation—‘I see / my loneliness/ a trench inside me’—as Mamoun gives space to all the memories that pronounce themselves in her mind. Through their acknowledgement, they seem to provide the poet with comfort, if not closure.

There is a steady, unhurried cadence to the collection, achieved through the use of additional spacing, which contributes to the introspective and intimate quality of Mamoun’s writing. Each additional space allows room for breath, resulting in a resolute pace and stillness throughout the collection. Given the personal subject matter, it feels right to read the poems in your head, as they once lived in Mamoun’s. While it could be easy to overly furnish these understated pieces, Yasmine Seale’s translation retains the fluidity and lyricism of Mamoun’s writing, eschewing the confinement of punctuation, capitalization, and justification to reflect the cascades of emotion served by the Arabic language. This is evidenced in the opening poem, which adopts the linguistic composition of the Arabic, the peaks and valleys, differently ordered:

empty now the street

is bleak trees line it

silent bare holding

their ground the street in

its loneliness its general

stillness is beautiful &

for all the signs of death

it bears it promises life

Seale also preserves the literary conventions of Arabic, with flowing ampersands in place of commas or breaks:

I live secluded

behind thick drapes

with fears & hopes &

wishes & vast loss

Yet, while funneling Mamoun’s waterways of thoughts and feeling with delicate translation, each poem reads as free of intervention or refraction. It is an admirable accomplishment to evoke the original language of a poem while manufacturing naturalism; a deep respect for the original work’s transparency and intimacy shines through Seale’s translation.

While Mamoun’s motivation for writing Something Evergreen Called Life was expressly personal, as the author’s means of connection during the repressive times of contagion and exile, the collection feels familiar—perhaps a result of the shared experiences of ceaseless fear and sadness that colored each moment during those first months of 2020, or maybe invited by the familial tone with which Mamoun exposes her real-life experiences to the reader. Something Evergreen Called Life succeeds in putting language to the common—but so often unmentioned—emotions that overwhelm each of us. It is a comfort to know that we are not alone in our loneliness: that even our most trying moments and haunting memories, we can be seen and understood by another. By exposing her soul with admirable honesty, Mamoun paves the way for readers fighting their own battles. She stands as admirable not only for what she has overcome, but for her transparency while awash in darkness; Something Evergreen Called Life is an uncommon salve, a remarkable acknowledgement that not all is okay, but, treading water, we continue to press forward.

Bridget Peak is an art educator hailing from Montana, USA. She presently works as a Fulbright Researcher in the Art Education Department of Sultan Qaboos University in Muscat, Oman and serves as a digital editor at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: