Emptiness, desolation, and thirst—these evocations of the desert are the ones most familiar to the bulk of us, but for some, this wild landscape resists such simple evaluations, holding instead a kingdom of history, knowledge, and narrative. In this essay, anthropologist and writer MK Harb takes us through the literature of the North African author Ibrahim Al-koni, whose sagas reveal the historic philosophy that these regions have preserved. Despite the othering hierarchical nature that has plagued literature, Al-koni’s writings invoke tender and human shapes from his landscapes, arising from that mysterious creature: the Sahara.

MK Harb recommends listening to this playlist while reading this article and the works of Al-Koni.

The mahri convulsed and its skin turned bloody red. It jittered with pain, its stomach containing a fire burning within and howled “Aw-a-a-a-a-a-a-a.”

Ukhayadd had given the mahri a silphium plant known for its magical capabilities for physical healing, but also for its mind-twisting qualities. Ukhayadd himself began to convulse, through his emotions he felt every bit of the pain the mahri was going through. He pleaded to the various gods in the Sahara from Allah to those guarding the temples to transfer the pain on to him. He yelled “Lord, divide his share of pain. Let me be the one to lighten his burden,” but the mahri still jittered and yelled “Awa-a-a-a-a-a-a.”

Ukhayadd’s emotions then turned to anger. He pleaded with the mahri, yelling “do you think you can escape your fate? Brave men do not try to run from themselves. Wise men do not try to flee from fate.” Ukhayadd did not see the mahri as a horse. He shared with him a sort of otherworldly love and addressed him with the various emotional capacities you would with a human.

This imagery ripe with lore and the transfiguration of pain comes to us through the words of the novelist Ibrahim Al-koni. Al-koni is a prolific writer, having penned over eighty novels, with his most famous being The Bleeding of the Stone (translated by May Jayyusi) and Desert Gold (translated by Elliot Kolla), from which this preceding passage of Ukhayyad and the mahri comes. Al-koni hails from Libya, though he does not identify as a Libyan author; while he comes from the land that is now nationally defined as Libya, he is unwilling to commit to nationalist or modern labels. Having grown up in the traditions of the Tuareg, an Amazigh group that inhabits the borders in and out of the Sahara and whose cultural and geographic traditions were heavily disrupted by the imposition of colonial and national borders, this nomadic upbringing seeps throughout his words. His writing is divorced from a need to construct urban environments or a sense of linear time and space; instead, it is imbued with a Sahrawi melancholy, which conjures up vast plateaus that are full of events as enthralling as those unfolding in cities.

The image of the desert or, more specifically the Sahara, has occupied the imagination of many. Whether as Sufi mystics seeking refuge in the solitude of the desert to practice oneness with God and transcendence, or a political landscape exemplified in the work of Palestinian author Ghassan Kanafani’s Men in the Sun, where it becomes synonymous with the treacherous journeys many refugees go through. The desert in the western canon, particularly from the twentieth century onwards, occupies a specific paradigm of orientalism. It becomes a “timeless” and “placeless” geographic entity where the bourgeoisie subject can shed their urban persona and engage in an exotic endeavor. The desert in that imagination is the antithesis of the urban European city. Perhaps the most famous orientalist of the desert is T. E. Lawrence, commonly known as “Lawrence of Arabia.” A British soldier and archeologist, Lawrence was active in the Arab Revolt of 1916 against the Ottoman Empire, though he is more known for performing a sense of “bedouin” identity and setting the standard for the marketing of the “desert fantasy” for media ranging from Hollywood films such as Lawrence of Arabia (1962) to dancers at Coachella. In her essay, “Gender and the Culture of Empire,” scholar Ella Shohat argues that T.E. Lawrence’s adventures in the desert represent a landscape for the “romantic genius” of the west to come and invigorate the dormant Arabs into revolt. Anthropologist Steve Caton, in his study of the film Lawrence of Arabia, complicates her argument, indicating that the desert becomes a subversive landscape of both orientalism and anti-imperialism. Lawrence is both a “romantic genius” and a “romantic fascist” who is an agent of imperialism. Building off both arguments, we understand the desert to have an othering capability. It becomes a way of introducing cultural difference, whether in literature or film.

Ibrahim Al-koni’s use of the desert as a landscape is unique. At a talk Al-koni gave at the University of New England, he equated the desert with freedom and with the absence of the state. He argued that “we cannot talk or write about freedom as creatures conditioned by authority,” and in the desert, the absence of the said authority is outstanding. Al-koni understands the desert to have a freeing quality as a space where humans can reflect on existential matters such as “the unity of creatures,” “the problem of authority,” and the “meaning of identity.” This comes from the desert’s ability to collapse modern constructs of urban society, from linear time losing value to urban language losing context and meaning. Al-koni isn’t expanding our understanding of the desert in an exaggerated and orientalist sense as a place of lawlessness and adventure, but giving the desert an ideological value that he believes has been lost.

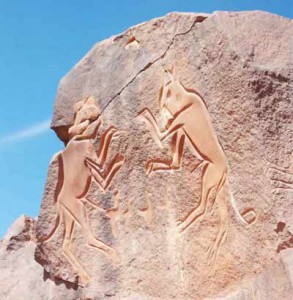

In his novels, Al-koni does not write or come to the idea of the desert from an urban understanding, nor does he frame it as a landscape neighboring the city, but as a world of its own. Reading The Bleeding of the Stone, we understand the importance he places on the “unity of creatures” and cosmic harmony in the desert. The novel opens with its protagonist Asouf, a Tuareg herder who guards the ancient temples of the Metkhandoush valley. Asouf lives alone in the Sahara, but is occasionally visited by “Christian tourists,” who come to observe the engravings of the temples or camp out next to it. He does not take or request money from them since in the realm he lives in, there is no value for monetary exchange. Instead, the tourists occasionally leave him biscuits and food to enjoy. Now, the name of Asouf is important to reflect on; in her study of spiritualism and symbolism in the novels of Al-Koni, scholar Meg Furniss Weisberg explains that “the word ǝsuf (also transliterated as asuf or essuf) in Tamasheq, the language of the Tuaregs from this region, means solitude(s), outside, exterior, wilderness, or unknown.” Hence, the protagonist becomes synonymous with the landscape of the desert and an extension of it. Asouf is described as a Muslim man, but also as one who is able to comfortably exist between the region’s pre-Islamic past and its present. This is evident in a line where Al-koni writes:

All unwittingly, Asouf had failed to direct his prayer towards the Ka’ba. Instead, while prostrating himself, he’d been facing the stone figure towering above his head from the depths of the Wadi.

Asouf does not see his actions to be blasphemous, as he does not treat the prehistoric figures as pagan or harmful to his religion. Here, Al-koni is commenting on the rigidity and the heightened conservatism that has plagued Libya and many other countries in the region with the arrival of political Islam. In his talk at the University of New England, Al-koni also stated that the inspiration for The Bleeding of the Stone came from an event that happened in his childhood. On a visit to the temple in Metkhandoush valley with his brother, he saw bullet holes in the walls of the temple. He asked the guide about the matter and was informed that soldiers of the former Libyan dictator, Gaddafi, had shot at the walls. Al-koni could not understand how individuals can become so vengeful and ignorant so as to shoot at ruins from their past. Hence, he set out on a course of writing that highlights the importance of the harmony and cosmology of the desert from its ancient past to its future.

The Fighting Cats, Metkhandoush Valley; Photographer: Uknown.

The Fighting Cats, Metkhandoush Valley; Photographer: Uknown.

Returning to Asouf, we witness the approach by which Al-koni places him in a world of ecological harmony. Asouf is one day visited by two men from the mainland of Libya who approached him with a menacing vulgarity. Upon greeting Asouf, they ridicule him by mentioning that they had heard about him being “the one who’s happier living in an empty desert than being with other people.” One of the visitors, a tall and blunt man called Cain, whose biblical naming invokes a familiar imagery, informed Asouf he was here to hunt the infamous waddan. The waddan is a horned sheep known for its tenacity and prominence among the creatures of the desert. Asouf vehemently denied the presence of any waddan, claiming they no longer pass through these regions. Cain was infuriated. He informed Asouf he has an obsession with meat and that he had come after the prized flesh of the waddan; Cain does not see the waddan as a creature in the same manner Asouf does, rather as an exotic delicacy. Al-koni uses these two characters to address the gluttony and over-consumption many individuals in urban societies deal with.

The men persist in their quest to find the waddan, and later in the novel we discover Asouf’s real reason behind denying their existence. Asouf had often gone hunting with his father, who valued solitude and despised the company of people, but on each endeavor, his dad would not teach him how to fight the waddan or hunt them. Asouf would get frustrated and demand his dad to pass on this knowledge, but he refused. One day, Asouf’s mother informed him that his father made a vow while hunting and could not teach Asouf how to spill the blood of the waddan. She explained:

He was hunting on the slopes of the Aynesis, and his foot slipped. He found himself hanging between earth and sky, holding on to a rock with his legs dangling down into a chasm. He’d given up all hope, But the very beast he’d been fighting and trying to kill brought him out and saved him from death. Now do you understand?

Asouf was shaken. His mother continued to inform him that his father had to one day break the vow and in turn, it broke his spirit. She was pregnant and they were suffering from hunger, which led Asouf’s dad to hunt the waddan. After, he wept all night and informed his wife that “he’d broken his vow and the spirit of the mountains would punish him for it.” He then assured her he would not teach his son how to hunt the waddan. And indeed, Asouf’s father was later lost to the mountains during a fight with the animal. Asouf then took his father’s promise to heart and refused to hunt or spill the blood of the waddan. He would nourish himself on a vegetarian diet, occasionally eating from the meat of the goats he herds. Through this intergenerational transference, we understand the importance of emotions such as reverence and remorse that exists between the creatures of Al-koni’s Sahara.

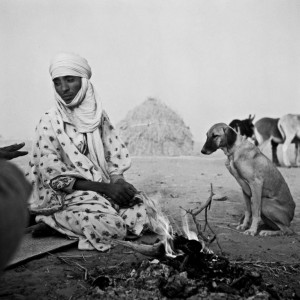

Tuareg; image credit: Bernus/Bernus Estate.

Tuareg; image credit: Bernus/Bernus Estate.

Asouf’s family trappings with the waddan are part of the epochs and musings that Al-koni writes to underscore the value of harmony and coexistence among creatures. In his A Sleepless Eye: Aphorisms from the Sahara, translated by Roger Allen, we see the value he places to all beings of the earth. In these aphorisms, he talks with compassion about the various elements of life from trees to wind and water, accompanied with certain truths and affirmations. He romantically personifies water, addressing it as a “saint who dies in order to give life,” and affirms that “wind was only created to make trees living creatures.” To him, all these elements are connected, and together they are able to engage in the creation and sustenance of life. In contrast, what most humans engage in is a disruption and a blatant disrespect of living beings.

In his aphorisms, we also come to a closer understanding of his mystical reverence of the desert, a precious landscape of which he says:

Desert is conflict in conflict with existence, but in harmony with its adversary nothingness.

The Desert’s enchantment is borrowed from that of eternity.

Desert is paradise, not through water but freedom.

Desert is a paradise of nothingness.

The desert for Al-koni is a multitude. In writing, it offers him a freedom to elevate it to a holy and spiritual status, giving it a form of power beyond comprehension, but it also offers him the ability to use its landscape to engage in sociopolitical commentary on modern society and the ails that plague his region. In doing so, he is able to use this landscape of “nothingness” to conjure up epochs ripe with socio-political commentary, without needing to use a specific language in naming cities, countries, or time. His writing has a hybrid language, borrowing from Arabic and Amazigh languages while bringing back extinct words to create a lexicon worthy enough for prose about the desert. During his talk at the University of New England, he defends his choice of creating such a lexicon by arguing that to discuss the matters of the desert and address the questions it poses, there needs to be a new language—one that is not religious or urban, but hybrid and mythological. In his story, Anubis: A Desert Novel, there is a part that truly encapsulates this linguistics. In it, the protagonist Anubi talks of apparition, ghosts, losing language, and coming back to it, saying:

With the assistance of my Ma, I began to rehabilitate my tongue, for I had lost control of it during my journey through the unknown. I remembered obscurely that I had once mastered this astonishing organ, even though I did not know how I lost control of it. Apparently, while I slept I had lost the tongue’s secrete along with the secret of my prior existence.

This haunting passage illuminates the multiple meanings language holds for Al-koni. It is a part of many realms and in relation to various experiences, lived and imagined. For him, language isn’t singular and transactional, and has various processes of learning and unlearning it.

Few authors are able to create a world that combines the ghosts of ecology, the apprehension of humans, and the ailments caused by the sociopolitical dimensions of capitalism, yet Al-koni does just that. Reading his work at this present moment is eerily relevant as the world is ripe with global anxiety on the future of our planet, and the ecological calamities to come. Yet, the writing is also enveloped with tantalizing mythology that is able to produce optimistic images of alternative futures and landscapes, in which planetary harmony and ecology are lived and understood in different ways. In his aphorisms, he tells us: “We are obsessed with our bodies for fear of deadly disease, and to the same extent commit the basest evils against Nature, forgetting that it is our most important body.” So it is that within his body of work, we find an urgency and a constant call to action for a heightened awareness of our place in the world as not selfish beings, but fellow creatures.

MK Harb is an anthropologist and writer from Beirut, Lebanon. He received his Master of Arts in Middle Eastern Studies from Harvard University, and his research focuses on cities, architecture, and escapist consumer culture in the Arab world. His work has been published in Columbia University’s Journal of Politics and Society, Hyperallergic, Art Review Asia, and Reorient Magazine. He is currently working on a novel pertaining to the energy economy, migration and the hallucinatory experience of post-oil Arab cities.