Last week, we recommended readings from Asymptote‘s summer issue, “The Dive”. If you are still uncertain about where to take that first plunge into our jam-packed issue, take guidance in this week’s recommendations from some of our Section Editors. What’s more, definitely don’t miss the coverage of the issue in “This Week in Short Fiction” at The Rumpus!

***

“A Man Composing a Self-Portrait out of Objects,” from The Absolute Gravedigger, by Vítězslav Nezval, tr. Stephan Delbos and Tereza Novická. Review: Aditi Machado, Poetry Editor.

I like weird poetry. Poetry that enacts the essential weirdness of trying to figure out stuff. For instance, when language tries to work out what a thought is or what thinking feels like, that’s weird. All of this seemingly abstract, matter-less matter turns into an ungainly body of odd parts that keeps connecting and breaking off and turning into other, still odder, parts. That’s what Vítězslav Nezval’s poem, “A Man Composing a Self-Portrait out of Objects,” feels like to me. To paint this internal picture, the man has to handle the external world of solid, but changeable, things:

“Dismantling / A very intricate clock / Assembling from its gears / A seahorse / That could represent him before a tribunal / Where he would be tried / By five uniformed men from the funeral home / For his pathological absent-mindedness.”

Nezval’s translators have done an excellent job of embodying in English the slippery act of cobbling together what can never entirely cohere—a self. I recommend this excellent poem and eagerly await the book in which it will appear, The Absolute Gravedigger. (Twisted Spoon Press, forthcoming in 2016.)

Wind in a Violin, by Claudi Tolcachir, tr. from Spanish by Jean Graham-Jones. Review: Caridad Svich, Drama Editor.

Jean Graham-Jones’s translation of an excerpt from Claudio Tolcachir’s play Wind in a Violin is an exuberant, funny, and rueful piece. It has this sort of gossamer effect when you read it. The language sparkles and surprises. The actress Celeste finds herself in a precarious and yet strangely uplifting situation. You follow Wind in a Violin with the kind of expectancy present in the best drama, traversing ground that is morally and emotionally ambiguous. Tolcachir is a major figure in Argentine arts and letters, and Jones’s sensitive rendering of his text celebrates the author’s mischievous artistry.

David Shook on Translating “Bät Riting” by Jorge Canese. Review: Ellen Jones, Criticism Editor.

Complementing this issue’s special feature on multilingual writing is an essay by David Shook that describes the exciting and infinitely complex process of translating a short prose poem by Paraguayan writer Jorge Canese. The poem poses a significant challenge for the translator, as it blends and bends varieties of different languages into a unique idiolect. In thoughtful, sparing prose David muses on the processes of linguistic “corruption” necessary to reach an accurate translation of a poem of this kind, how Canese’s work demonstrates the unnecessariness of complete understanding, and, ultimately, the ephemerality and multivalency of “this mysterious gift called language.”

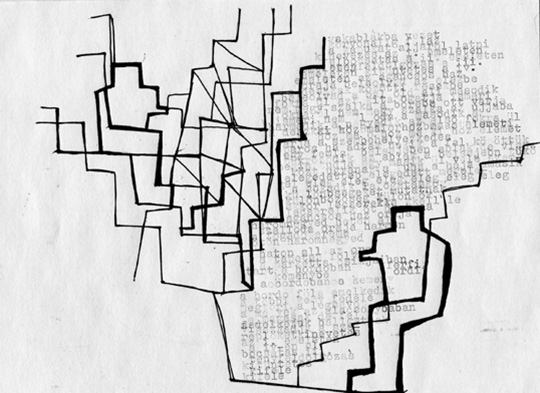

Voice and Machine, by Kinga Tóth, tr. from German by Eva Heisler. Review: Eva Heisler, Visual Editor.

The clacking of a manual typewriter’s keys. The whir of machinery in a meat-packing plant. The whine of a crane hoisting a cargo container. The hum of a dialysis machine. These are some of the sounds evoked in the visual poems of poet, musician, and artist Kinga Tóth. English, German, and Hungarian phrases—hovering at the threshold of legibility—are surrounded by contour drawings, abstract patterns made with a manual typewriter, and rubbings Tóth created by placing her poems on vibrating machines in the factories where she has worked. Tóth’s poem-drawings playfully explore imaginary interactions of voice and machine.

*****

Read More from the Asymptote blog: