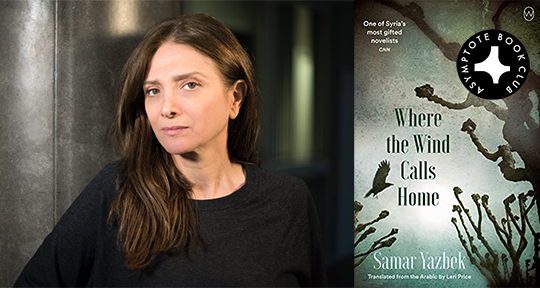

Samar Yazbek’s Where the Wind Calls Home is a poetic rumination that shifts through the land of the dead and of the living, between thinking and intuiting, and from the vast destructions of war to its intimate, embodied experience. In taking us to the “other” side—that of the military—in Syria’s unsparing civil war, Yazbek offers a method of understanding pain’s blind immensity, as well as the metaphysical phenomenon of life at the precipice of death. With the incredible work of translator Leri Price, whom Yazbek calls here her “voice in English”, Where the Wind Calls Home arrives to us with all the weight of contemporary tragedy, and all the light of a spiritual encounter. Here, Yazbek and Price speak to us on the recurring motifs of the text, the fluidity of the prose, and how writing can reveal to us our own secrets.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Alex Tan (AT): Samar, in your previous novel, Planet of Clay, we follow the perspective of a mute girl from Damascus, caught in the middle of the Syrian Civil War. For Where the Wind Calls Home, why did you select a dying soldier as your protagonist?

Samar Yazbek (SY): First of all, we’re not sure if he will die—what will happen to him, and with his life. Actually, it was a challenge in my own life, because I was in exile from myself, and I had stopped writing literature. I came back with Planet of Clay, to literature, but when I decided to write this novel, I started writing it as poetry. I tried something different. It’s a very personal thing.

Ten or twelve years ago, I decided for the first time to speak about the victims who are living on the other side of the Assad regime. It was a very difficult choice for me. There’s a perception that the soldiers on the side of the regime are not victims, but the problem is that this has been a long war, and everyone is a victim. And what we’ve got to remember is that there’s a class element; we have to remember the poor. A fundamental part of literature, in my opinion, is that we learn to look at things from an alternate point of view, and to have empathy with others. Without that, it’s absolutely certain that things won’t change.

AT: The figure of the tree plays such a central role in the novel—it becomes this recurring motif, with Ali crawling towards it in the narrative present, and thinking back to all the trees that have shielded him, including the one next to the maqam. Did you have any specific personal, religious, cultural, or literary motivations in opting for the tree as the essential anchor of the text?

SY: There are lots of reasons. First, every maqam in the mountains has trees. They’re all surrounded by trees, and these trees are huge and ancient, hundreds of years old. Second, the tree acts as refuge for Ali. It represents a shelter from daily violence—from the sort of physical violence that he encounters in the village.

The most important thing is that trees are silent. Trees die standing, silently, without speaking the language of humans—and in this death they have dignity. Ali is able to communicate with the tree, together in their silences. Silence is Ali’s language, his way of resisting against the violence in his society, so he invents a new language with the trees, with the sky, with the wind. It’s like he builds a bridge between himself and all the elements of nature. Trees are part of his world.

I’m also talking about myself and my vision; I believe we need to be like a tree sometimes.

AT: I want to pick up on what you said about the language of the trees being Ali’s language in the novel. I’m also thinking of what you said earlier, that the novel began as poetry. Could you tell us how it evolved from poetry into the novel, and whether you think the novel becomes a good channel for this silence? READ MORE…