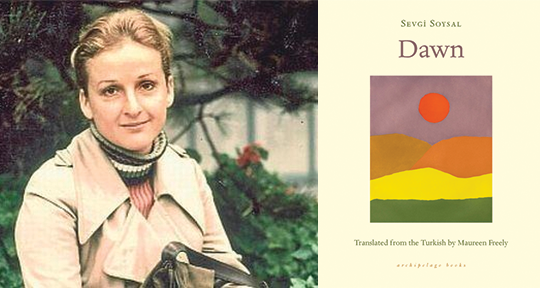

Dawn by Sevgi Soysal, translated from the Turkish by Maureen Freeley, Archipelago Books, 2022

Writing in the 1990s, the Turkish literary critic Berna Moran praised Sevgi Soysal’s Dawn for its historical urgency, but noted that it would not be a novel that survived the test of time—that its themes would lose their relevance. Perhaps Moran was optimistic in thinking that women’s struggles and militarism would be issues of a distant past in the years to come, or perhaps he undermined the strength of Soysal’s formal innovations. Whatever his reasons might be for painting the novel as a historical relic, his prediction did not come true; Dawn is now more relevant than ever, with Maureen Freely’s flawless English translation.

Soysal isn’t a stranger to English-speaking audiences. Her novels Tante Rosa and Noontime in Yenişehir have been translated into English, and she is a legendary figure in the history of feminism in Turkey. Along with writers like Leyla Erbil and Adalet Ağaoğlu, she defined the écriture feminine of Turkish literature long before it was coined and theorized by Western feminists. The eccentric, self-reflective, and often ironic tone of their protagonists reflected on what it means to be a woman—not only in a modernizing Turkey, but also in a leftist milieu dominated by men. While women’s struggle and sexual autonomy took the back seat in the leftist quest to liberate “masses,” these authors problematized the very notion of “masses.” Did the dream of a liberated people also include liberated women? The tension between how the outside world views liberated, intellectual women and how they view themselves is often the driving force of such novels, and hence their writing is often turned inwards, with sharp observations of situations and characters.

Dawn is a visceral and cinematic example of this kind of writing: where the embodied social experience of women takes central stage. It is also, as Moran notes, a novel about militarism and incarceration. Written in 1975, after Soysal’s own imprisonment following the 1971 coup, the novel situates the woman’s body in its confrontations with authority. The brilliance of the novel might be traced to the formal structure through which the author reflects on this confrontation; ever the innovator, Soysal sets her novel within the course of a single night, interspersing the narrative with flashbacks of different characters. The stories beget other stories of individuals becoming situated in their own relation to authority, only to return to the “present” moment where they are confined within the four walls of the town jail. A single night becomes the microcosm of the Turkish experience of militarism, gender inequality, and sexuality. READ MORE…