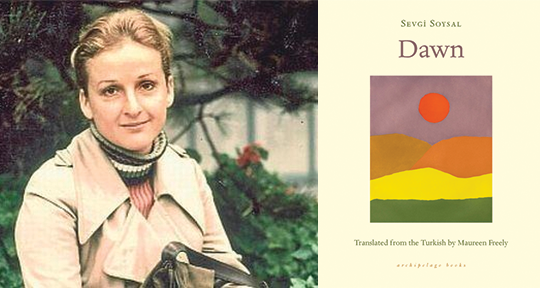

Dawn by Sevgi Soysal, translated from the Turkish by Maureen Freeley, Archipelago Books, 2022

Writing in the 1990s, the Turkish literary critic Berna Moran praised Sevgi Soysal’s Dawn for its historical urgency, but noted that it would not be a novel that survived the test of time—that its themes would lose their relevance. Perhaps Moran was optimistic in thinking that women’s struggles and militarism would be issues of a distant past in the years to come, or perhaps he undermined the strength of Soysal’s formal innovations. Whatever his reasons might be for painting the novel as a historical relic, his prediction did not come true; Dawn is now more relevant than ever, with Maureen Freely’s flawless English translation.

Soysal isn’t a stranger to English-speaking audiences. Her novels Tante Rosa and Noontime in Yenişehir have been translated into English, and she is a legendary figure in the history of feminism in Turkey. Along with writers like Leyla Erbil and Adalet Ağaoğlu, she defined the écriture feminine of Turkish literature long before it was coined and theorized by Western feminists. The eccentric, self-reflective, and often ironic tone of their protagonists reflected on what it means to be a woman—not only in a modernizing Turkey, but also in a leftist milieu dominated by men. While women’s struggle and sexual autonomy took the back seat in the leftist quest to liberate “masses,” these authors problematized the very notion of “masses.” Did the dream of a liberated people also include liberated women? The tension between how the outside world views liberated, intellectual women and how they view themselves is often the driving force of such novels, and hence their writing is often turned inwards, with sharp observations of situations and characters.

Dawn is a visceral and cinematic example of this kind of writing: where the embodied social experience of women takes central stage. It is also, as Moran notes, a novel about militarism and incarceration. Written in 1975, after Soysal’s own imprisonment following the 1971 coup, the novel situates the woman’s body in its confrontations with authority. The brilliance of the novel might be traced to the formal structure through which the author reflects on this confrontation; ever the innovator, Soysal sets her novel within the course of a single night, interspersing the narrative with flashbacks of different characters. The stories beget other stories of individuals becoming situated in their own relation to authority, only to return to the “present” moment where they are confined within the four walls of the town jail. A single night becomes the microcosm of the Turkish experience of militarism, gender inequality, and sexuality.

Oya and Mustafa are the main protagonists of the fateful night. They are both leftists recently released from prison and, as luck would have it, their paths cross in the town of Adana at a dinner hosted by Mustafa’s worker uncle. This unfortunate coincidence attracts the attention of the town’s military and police authorities, and they decide to raid the dinner with hopes of finding something incriminating. No crime has been committed, but protagonists of the novel know that “guilt” is an arbitrary construct, applied to whoever the state deems as threatening its fragile order. It is no accident that the characters of the novel include Alevis, Kurds, radical women, dispossessed workers, and sex workers: the usual suspects of the state.

As the door is kicked in by the police, the time of the novel freezes and, just as in a Cubist painting, the event is witnessed from different perspectives of the table. Mustafa’s uncle and his extended family, Mustafa’s brother, Oya, Mustafa, and a petit bourgeois guest all experience this interruption from their own class and gender positions. Unlike socialist realist novels popular in Turkish literature since the 1950s, however, Soysal’s novel neither takes a romantic approach towards its characters nor a dogmatic one towards its subject matter. The characters constantly question their idealism, and ordinary citizens are not simply of the innocent worker class, who will eventually rise against the system that subjugates them. Helen Mackreath writes that “[Soysal] does not fictionalize individuals as heroes (or villains), but places them within the context of their surroundings, giving life to all the circumstances which shape their flows of becoming.” Indeed, even the police officer who is charged with “interrogating” the dinner guests has an unexpected moment of empathy when Mustafa’s uncle’s mouth—under torture—reminds him of his fish at home.

Through the different perspective of the dinner guests, the underlying gender dynamics of Turkish social life is revealed. As Mustafa is preoccupied with the wife he left behind when he was incarcerated, all his failures as a partner flash before his eyes and there, Soysal shines in her depiction of how a middle class, domestic life turns into a servitude for women. Mustafa wonders, “So what had been on [his wife’s] mind through all that? It had never occurred to him to ask, he now realizes. All he can remember is Güler cooking, Güler knitting in silence.” He also only then realizes that he was, in fact, the reason why his brilliant college girlfriend is now a ghost of her former self—a sad housewife whose only escape is in photo-novels. Thus, he keeps wondering during the dinner and detention whether he’ll be able to return to her, and salvage whatever is left of their marriage.

Oya, on the other hand, is self-conscious of her class position among this family. She is, after all, a bourgeois—albeit a radical one—who has more privileges than Mustafa’s aunt and her sister, who are now serving her dinner. She is shamed “to be the only woman at the table, to be served by Gülşah and Ziynet and to see them left standing, her own privileges so starkly revealed. But Gülşah and Ziynet didn’t even question it. Oya is not like anyone they know. And that’s fine with them. They hardly think about it. In their eyes, Oya is neither a man nor a woman.” She remembers other women she met in prison, and the reasons behind their incarceration: some jailed for obeying their husbands in fear and breaking the law; some for killing their lovers. In this sense, Soysal’s account of gender becomes an intersectional one, noted by Adak as she peels the different layers of oppression women face.

But it’s not only her class position that makes Oya uncomfortable. She is also self-aware of her embodiment of a woman. After the birth of Turkish Republic, a lot of emphasis was put on women’s literacy and education. In contrast to the Ottoman Empire, the women now had the opportunity to become teachers, pilots, or doctors. However, as Maksudyan and Alkan note, “conditions of women’s presence in public spaces [were] to be kept within the limits of asexuality.” Women could not present themselves as sexual beings and those who did act on their desires were considered immoral and promiscuous. Oya is well-versed in performing this sort of femininity, in blending herself to her surroundings, becoming invisible as a woman—but authority is also well-versed in reducing the women to their bodies to degrade them. As Oya looks at the truncheon left on the table in the interrogation room, she remembers how other inmates were raped. Soysal doesn’t shy away from describing these horrific experiences, building on the tension that comes with being a woman confronting a military authority. Yet, there is one thing even more terrifying than the truncheon: Oya is petrified that she will have her period during the interrogation, and frustrated that she should be ashamed of her body in this way. She thinks: “It’s how we’ve been conditioned. If we see our own bodies as shameful, if its untold secretes are mysteries even to us, if we censor our thoughts, lest they be judged evil, how are we ever to stand up for our beliefs?” The tension builds, until readers are made to feel the discomfort in their own bodies.

So, why is Dawn still relevant today? In her preface to the novel, Maureen Freely observes that “like Orhan Pamuk’s Snow, it is the Turkish tragedy writ small. In contrast to Snow, it subjects that tragedy’s scars and fissures to a female gaze.” But the novel doesn’t just complete Turkish historical narratives by supplementing it with the woman’s perspective. It also functions as an intersectional lens whereby different forms of marginalization combine. Dawn is surely ahead of its time in laying bare all the facets of discrimination and privilege; Soysal’s writing is captivating, reflective, and thrilling. The military coups and history of Turkish left are indeed specific local contexts, but the dream of women’s liberation remains an unfinished business in many parts of the world. Dawn is a classic that readers interested in feminist world literature will devour.

Irmak Ertuna Howison is a scholar of literature from Istanbul. She teaches Composition, Philosophy, and World Literature courses at Columbus College of Art and Design. Her publications include academic articles on pedagogical approaches to teaching world literature, feminist crime fiction, and popular books on Jane Austen and Mary Shelley.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: