“Clarice inspires big feelings. As with the ‘rare thing herself’ from ‘The Smallest Woman in the World,’ those who love her want her for their very own. But no one can claim the key to her entirely, not even in Portuguese. She haunts us each in different ways. I have presented you the Clarice that I hear best.”

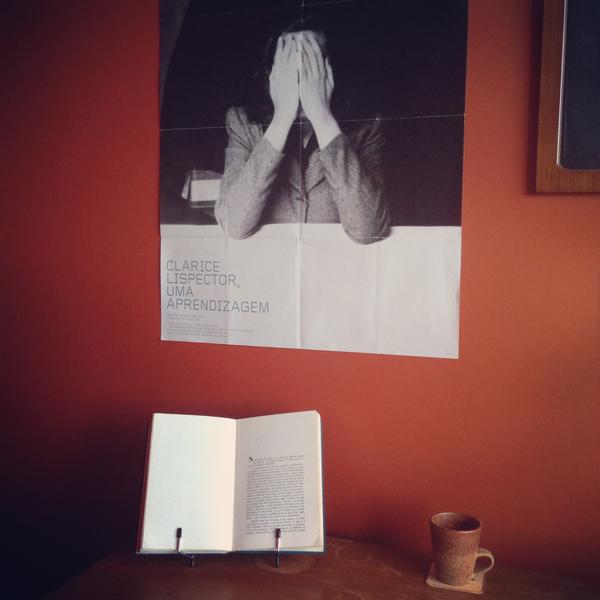

By spending the last two years translating nearly four decades of Clarice Lispector’s work in what she calls “a one-woman vaudeville act,” Katrina Dodson has joined a club of translators (trumpeted by Lispector’s biographer and de facto proselytizer, Benjamin Moser), whose interpretations of the Brazilian writer have now generated a skyscraping tidal wave. Though recognized by Brazilians as their greatest modern writer, Lispector was little-known among English-speaking readers until the beginning of this decade. Today, she is the first Brazilian writer to appear on the cover of the New York Times’ Sunday Book Review (July 2015). For the first time in English, Complete Stories brings together all the short stories that established her legacy in Portuguese.

Lispector gives the impression of a woman looking from the outside in, always taking notes. Like Borges, she expects you to follow her fantastic trains of thought, but she is unconcerned as to whether you enjoy the ride or not. In Complete Stories, eggs become infinite metaphoric permutations (interestingly, Lispector would die of ovarian cancer, on the eve of her 57th birthday), a lonely, red-headed girl and a red-headed basset hound discover they are soulmates, but destined never to be together, and a woman has a face.

Because in Lispector’s world—and Dodson’s translation—it must be asserted that a woman has a face, as if such a characteristic is not naturally of this world. These familiar details, made new —especially during fevered sequences when geography reflects a character’s unraveling—are what end up grinding our faces into the pavement as Lispector gazes on, coolly, but not unkindly, with great curiosity from above.

***

MB: When did you first encounter Clarice Lispector, and did you have a form of epiphany moment when you discovered her?

KD: I first started reading her in 2003. I was living in Rio de Janeiro and teaching English at a private English school called Britannia, and I had moved to Brazil that year speaking some Portuguese but, but it was—I spoke French, and then I was listening to these cassette tapes. That’s how long ago it was [laughs]. I would listen to cassette tapes that they would use to teach the Foreign Service how to learn a foreign language. I would listen to these Portuguese tapes before going. READ MORE…