In his latest and perhaps most personal work, Argentine writer Andrés Neuman probes his newfound role as a father, reckoning with the masculine and the paternal with trepidation, honesty, and most of all, wonder. The arrival of a child is here fortified with the poetry of discoveries—developing ultrasounds, the first tentative words—and the sublime language of an expanded self, as both father and son come to find their new places in the world. At once a universal and a deeply private story, A Father is Born is a testament to where the mind goes when it is led by love.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

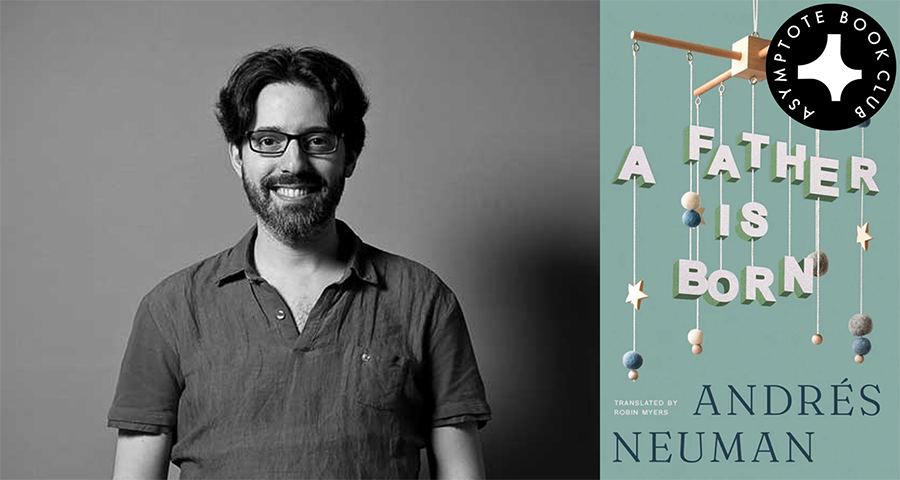

A Father is Born by Andrés Neuman, translated from the Spanish by Robin Myers, Open Letter, 2025

Andrés Neuman’s bios often begin by describing him as a son—specifically, that of Argentinian musicians who emigrated to Spain in the early 1990s. This intimate history has previously been explored in his writing, including in a collection of poetry about his dying mother, as well as a novel based on the dictatorship suffered by his family in Argentina. Now, continuing this occupation with lineage is a book that sees him wrested into a different position within the family: as a father to his newborn baby. A Father is Born was originally two separate texts, but arrives in English as a happy side effect of their translation by Robin Myers. The first, Umbilical, is a patient and forensic study of his and, to a lesser extent, his partner’s experience of expecting and then raising their child, Telmo, while the second, Small Speaker, explores the boy’s first forays into language and the mysterious assembly of a lexicon.

‘Little by little, I’m birthed as I speak to you.’ Each page of A Father is Born is akin to a poetic diary entry, ranging from the descriptive to the self-reflective. In the first section of Umbilical, titled ‘The Imagination’, Neuman explores the psychic nature of the fatherly bond pre-partum, detailing the subconscious effort of conjuring a loving connection to his future child. These opening chapters hum with the low frequency worries of a figure who knows about the precarity of life and miraculous ‘overlapping fates’ of ancestry: ‘. . . hands over hands over hands.’ In his wanderings around an expectant house, he realises how such fragility applies to the story he is building,

“More than their creator, I feel like their host,” your mother confesses.

Now I imagine us in concentric circles: you travel within a reality within our reality, which exists within ceaseless curves. What am I, then, in this home where your mother’s womb rocks and sways? Who do I inhabit?

These reveries see him come to terms with the truth that he will have to invent his own purpose, as so many baffled men have done before him. To me, this image of the father as outsider echoes a core English piece contemplating paternity: Kate Bush’s This Woman’s Work. Written from the perspective of a man standing outside the hospital room where his wife gives birth, she sings:

It’s hard on the man,

Now his part is over

Now starts the craft of the father.

With her body dedicated to the labour of birthing and nurturing, the woman works while the father crafts a narrative both for his child and for himself—yet he longs to be included in the bloody, corporeal affair of birth, to feel a closeness which transcends the limits of their physical forms: ‘It’s weird, son, isn’t it? Both of us here, in time, sharing matter, mixing our shadows together, our bones. . .’. In Small Speaker, Neuman addresses a hernia operation (an unfortunate consequence of carrying his growing son around) and concedes: ‘Walking together brings a secret pain, joy, and tear. At least I’ve put a little of my body into it.’ There is an unmistakeable glee in his masochism.

The imaginative labour of Umbilical builds to its climax in a section titled ‘A Minimal Monologue’—a section which, I confess, I found a little uncomfortable to read. Giving in to the urge to describe his son’s voice (which Neuman himself describes as an attempt equal to ‘a brush with failure, stutter, or cliché’), the narration is handed over to his newborn: ‘They talk to me. They seem to think I understand what they say. And even though I don’t, I do.’ It is discomforting because it resounds with earnestness, with barefaced desire—the father’s desire to become the beloved object, to inhabit him, to predict his unknowable and burgeoning awareness. It exposes this version of love for what it is, an ecstatic and embarrassing dissolution of the self.

Once his child is born, a new conversation begins. In Small Speaker, Neuman describes the coming together of two great loves: the boy and language. Despite his wonder at the rapidly organising soup of signs and sounds in Telmo’s head, he does admit the tragedy of transformation in the ever-morphing child, mourning the loss of his preverbal son as though he were withering like a cut umbilical cord: ‘The sweetest, darkest part of him is vanishing. Contrary to my expectations, I realize I’m going to miss my wordless boy.’

Translator Robin Myers enjoys language just as much. Consider the matryoshka-like symmetry of the following: ‘I’m the one awaiting you without gestation, a man baffled to be born a man, who clothes your shape and carefully folds, one by one, his limitations.’ The economy of each brief chapter—some no more than a few lines long—require a poet’s precision, and Myers is clearly at home. She channels Neuman’s affinity for metaphors, which often play with scale, showing us how words can be everything and one thing, ‘Your whole soul is a body: a monk of organs. Cathedral-like, you echo when you cry.’ Reading lines like these feels like staring into Borges’s Aleph.

Small Speaker ends with two stories created, we are told, by Neuman’s son. In the irresistible style of children’s imaginings, they borrow from the tropes of familiar tales and add in something wildly mercurial, untethered from logic or convention. ‘Once upon a time, there was a ship and . . . it missed its water. Then there was a boy who brought some. He brought it from the sea. In a bucket. And Mama.’ The child’s first experimental steps into the father’s authorly world mark a different kind of exposure, one which constitutes an inherent part of being a writer, yet is still an exercise in vulnerability. ‘I want our conversation free of any emotional police’, the narrator wishes, willing the words to act like a protective charm in a text so weighty with feeling. It is this dedication to unguarded emotion which allows A Father is Born to shine, not only as a love letter to the child and his voice, but a lesson in how to celebrate the fictions that bond us to one another.

Maddy Robinson is an English writer and translator from Spanish and Russian. She holds a Masters’ degree in Comparative Literature and her work has appeared in publications such as The Kelvingrove Review, From Glasgow to Saturn, El Diario and Pikara Magazine. She lives in Madrid.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: