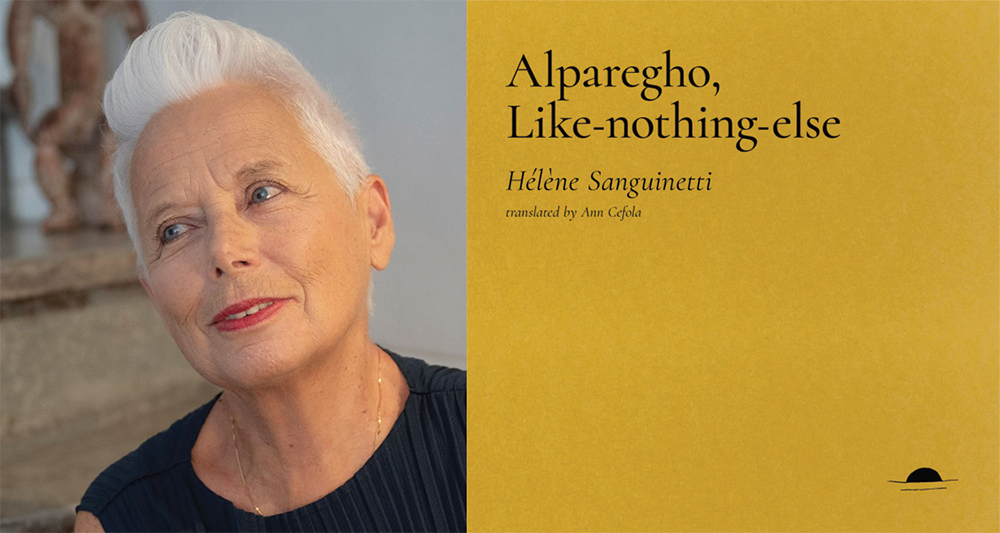

Alparegho, Like-nothing-else by Hélène Sanguinetti, translated from the French by Ann Cefola, Beautiful Days Press, 2025

Today is the day! “It’s today, / great day! / Let’s shake sheets out / the windows, / smash panes and / replace them, / empty drawers, pockets, / shelves. / Great day!” Hélène Sanguinetti’s collection, Alparegho, Like-nothing-else breaks through walls, those we erect with mortar and brick as well as the more insidious ones we draw in our minds and on the Earth. Through Ann Cefola’s translation, Alparegho effortlessly draws readers into a patchwork of vignettes that question the solidity of home and country, suggesting that these supposedly immutable objects are heavy burdens; we would be better off leaving them by the wayside. In seven chapters, the poet increasingly brings to bear the oppressive characters of the nation-state and the domestic sphere, shattering their hegemony in a sweeping motion that sweeps her readers from one scene, one place to another, looping us back and around.

Sanguinetti’s long poetic career has exhibited a practice that moves between polyphony and plasticity, and the resultant sense of vertigo disorients the internal compass as one move forward through this collection, which incorporates elements of fables, dreams, and songs to disenchant its readers from the sorcery of capitalism and authoritarianism. Alparegho opens with a potent symbol of the weight of home on our backs: a snail creeps through the dark of the night of the house, leaving a trail of slime. From there, the author slyly and gradually suggests that the rooms of the house, or the lands of the king, are interchangeable squares on a chessboard, abstract concepts just as much as lived environments. Here, home is neither comfortable nor cozy, but a rotting mess, slowly caving in.

. . . Because water entered

suddenly as it had to,

unseizable water.Under the tunnel,

and even well before the station,

against walls,

man and cat piss,

smelled so

that we held our noses. . .

From there on, Sanguinetti returns to the snail as a central leitmotif while slinking away from the domestic anchor. These places of comfort and perceived safety are also, she implies, to be found and reinvented.

What house?

Someone climbs

the ladder,

as much to catch the moon

as to finally see

to understand the meaning of quests.

Yes.What house and what night. . .

In the pages that follow, we ascend this precarious “ladder” to catch the fickle light of the moon, then head out into the country to meet the titular character; Alparegho is a wandering landless prince, somewhere on the spectrum between Christ and Diogenes. He introduces himself in the first chapter, “Night throughout the house”:

“I am from the country of

the man with bandages,

the man without land and

without king,

he goes where he goes,

mule dead or lost, he

goes by foot,

with a rag and a little

water. . .”

In the second chapter, “This is everywhere,” the home takes the road to the country, and we are invited to wander a land where dwarves and giants coexist with dictators, whose beards are “stiff with worms.” The sharp concerns of the present coexist with an immemorial past, at once recognizably Medieval and (post)modern. Here, endangered species take refuge in caves, whose passages are barred to all others. Sanguinetti seems to suggest that we can never return to the idyll of our primordial origins, but must make do as best we can in a crumbling present.

In the third chapter, “A man died last night on the bridge,” Sanguinetti’s poetic athleticism and muscular simplicity are on full display. The chapter begins:

All day one looks over there by the bridge,

and for several days one looks

over there,

all river water below flows without extinguishing any

fire of this kind.

A man is dead, he caught fire.

Oh well, a man is dead.

The poet as an observer casts her gaze on the relentless daily tragedies of the world—but if the tragedy here is human, we are invited to look elsewhere and to place this potential martyrdom or suicide within a broader more-than-human context. As men perish, the wider world looks on:

Now

there is an immense silence on the river

immense immense silence

of cotton hearing itself.

It is almost as if, now that the human tragedy has ended, the rest of the world can sigh, breathe, and listen to itself again—can return to a more expansive polyphony of being. Still, in our world, the more-than-human must stay on the sidelines as the trials and tribulations of mortals take center stage, perhaps due to our noise and bluster.

As a collection, Alparegho was conceived by Sanguinetti after creating a hand-painted sculpture of the central character, complete with a garishly yellow head, bright red lips, and a beating red heart. Once she finished modeling the figure, she observed it and asked what it wanted from her. This isn’t the first time material forms have taken on poetic guises for Sanguinetti, who has often spoken about her admiration for athletes and dancers. For her, poetry can feel limp when stripped of orality and laid bare to dry on the page; thus, unsurprisingly, Alparegho disarms its readers with a forceful and muscular language that tenderly rips through.

Cefola’s translation artfully captures the violence and productive ambiguities of the original French. While Sanguinetti is known for her powerful performed readings of her work, she has also spoken to the importance of maintaining a multiplicity of interpretations, and this predilection for polysemy carries on in English, where the seeming simplicity of her poetics creates space for overlapping layers of meaning.

In her staging of her human comedy, Sanguinetti underlines the absurdity of our mishaps but suggests the intervention of the supernatural or the divine. As Alparegho parades through the verses and speaks directly to the readers, it strikes me as essential to remember that this entity was brought to life by the willpower of a colorful bust just as much as its human author. And while the Alparegho of this text takes on a decidedly human form as he sweeps through the narrative arc, one cannot definitively be certain of mortal status; he channels the power and force of nature, the pain of tragedy, the inevitability of catastrophe, and maybe a long arc (if not towards justice) at least towards balance.

This balancing out of human and (super)natural forces climaxes with a “let them eat cake” scene towards the end of the book, when a popular revolt in the garden of the King and Queen questions their authority. An insatiable crowd gathers, trampling on the flowerbeds and clogging their fountains, and a voice from amongst them calls out:

“Yes, more hungry than hungry, immeasurably hungry, and however, it’s true, we lack nothing, neither food, nor drink, each person has the portion that he needs, even more than he needs, each person is sensitive to the socio-economic progress, so evident and needed, Great Sovereign-on-the-Balcony, and each person is unhappy.”

This revolutionary movement could be from 1789, with the Parisian crowd that toppled the monarchy in Versailles, or from the yellow vests movement that has yet to guillotine late-stage capitalism. Alparegho easily weaves through the crowd of protestors, his flute forgotten, armed with a miniature golden ax. Eventually, the dream lifts and life plays on.

In the final pages, we learn something of where Alparegho came from, his home and country; this knowledge hints equally towards how common and extraordinary he is, painting a portrait of the land all of us live on and share. Through a deft sleight of hand, Sanguinetti conjures the epic and displaces the heroes’ quest into a porous contemporary context amidst the oppressed and marginalized. She seems to suggest what author and translator Monique Wittig explicitly states in her introduction to Djuna Barnes’s Passion: “What we need in a world where we are passed over in silence, literally in our social realities and figuratively in books, what we need whether we like it or not, is to establish ourselves, to come out of nowhere as it were, to be our own legends even in life, to make ourselves, flesh and blood beings, as abstract as characters in a book or painted images. It’s why we need, at a time when heroes have gone out of fashion, to become heroic in reality, epic in books.” Heroes haven’t quite gone out of fashion; they are everywhere in super-spandex, but the epic and aristocratic traditions have disappeared—and with them, these poetic lineages have been silenced. In honoring their legacy, Sanguinetti pirates these rich and varied tapestries to create a work of poetry that subverts and salvages traditions to create a beautiful and moving patch-work, a portrait of our age.

Christopher Alexander is a poet, performer and multidisciplinary artist. S he is currently engaged in a long-term investigation on interspecies communication and the performance of nature in the Mediterranean. Together with the visual artist and researcher Alexia Antuoferomo, they co-founded the collective of artists and researchers, Tramages. Heir texts and translations have been published in Asymptote, Belleville Park Pages, Pamenar Press Online Magazine, parentheses, Point de chute, FORTH Magazine, Fragile Revue de Créations, remue.net, and Transt’, among other publications. Heir work has been exhibited at 59 Rivoli, La Générale Nord-Est, Mémoire de l’avenir, and the Museum of Natural History in Paris. Heir first poetry collection, play-boy, explores the seepage of toxic masculinity into contemporary gender norms and is forthcoming in a bilingual edition with Le Nouvel Attila in 2026.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: