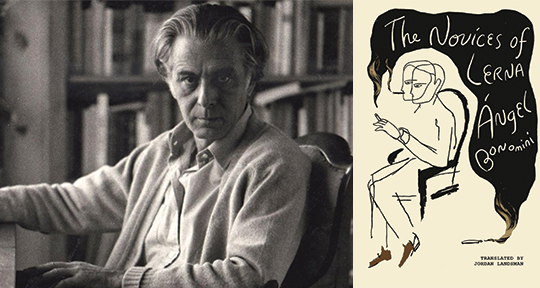

The Novices of Lerna by Ángel Bonomini, translated from the Spanish by Jordan Landsman, Transit Books, 2024

Ángel Bonomini is one of those extraordinary literary figures who—despite having been lauded for his singular, masterful inventions—has somehow fallen into oblivion. In addition to being a cultural critic and prolific translator, the poems and stories published throughout Argentina in his lifetime represented a vital contribution to the nation’s phenomenon of fantastic narrative. While he remained largely unknown to international readers in his lifetime, such work earned him multiple distinguished accomplishments in his home country—including two Premio Konex awards and personal accolades from Jorge Luis Borges. In 1994, at the age of sixty-four, Bonomini passed away, and sadly, his writing seemed to disappear with him.

Now, in The Novices of Lerna, Jordan Landsman has captured the author’s wistful and pensive voice in a stirring collection of sixteen previously untranslated stories, spreading the magic to a new generation of readers. With candles melted “as if light had been slit from their veins,” theories “woven like black thread in the dead of night,” and people “like books with transparent pages where the lines don’t match up,” Bonomini glides vividly and lyrically into worlds where time warps, people live and die and live again, doppelgängers are plentiful, sentences disappear into amorphous paragraphs, and Buenos Aires isn’t quite the same urban sprawl that one might see in Argentina. While the pieces in this collection have no crossover in plot or character, some subterranean power connects them, with favored symbols and images appearing and reappearing—figs, trees, fires, death, and the landscape of the city.

In the titular story, which takes up the first fifty-three pages of the book, the protagonist Ramón Beltra is invited to participate in a mysterious fellowship program at the University of Lerna in Switzerland. On his journey there, he briefly falls in love with a flight attendant, and while this love lasts for no longer than two pages, it serves as the emotional center for Beltra—and the reader—to hold onto when the trip soon unravels. The rules of Lerna are strange, with one being that the fellows are not allowed to distinguish themselves through their clothing, and this takes an absurdist turn when Beltra meets the other fellows, finding that they are all perfectly identical to himself. Commenting on this phenomenon, Beltra notes: “When a group wears the same uniform and its members are also physically identical, more than just equal and depersonalized, individuals are almost invisible.” Soon, the identical fellows begin to suspect that something unusual, even sinister, is happening to them; they fall victim to a mass epidemic, which wipes them out one by one.

Through this plot of the double, Bonomini takes the classic trope of the evil twin and turns it into a social commentary on finding oneself in a world of rigid, suffering homogeneity. Like Borges’ “Borges and I,” Bonomini splits character, wonderfully losing track of the narrator as a singular identity, and the off-kilter plot is complemented by the labyrinthine structure of the university: concentric circles, numbered apartments, an ominous forest, coffered ceilings, uncanny repetitions. Beltra confides: “I didn’t want to get lost like a rat in this maze, which was complex despite its seeming simplicity.” It is as apt a description for the edifice as it is for the narrative, which reads as if standing in a room of mirrors.

Of the collection, “The Bengal Tiger” is perhaps the most experimental; every line seems to contradict the one before it, as Bonomini subverts narrative structure in order to portray something ambiguous about the act of storytelling and fictional realities. The first paragraph begins with: “A woman is dancing and a scream is heard,” and ends with: “A dance screams up the woman that’s tigering.” A tiger eats the woman, but much of the material reality of this event, whether the animal is a physical entity or some representation of her husband or herself, is left unclear. Bonomini concludes this confounding text by stating: “Mankind will have isolated instants just as they have isolated atoms,” implying that the tale is a shattering of one into various contradictory narratives—a nuclear fission of a story. Jumping through time with no real beginning or end, it loops around itself in an ouroboros of love and betrayal, with the tiger activating endless transformations: “Every time it blinks, [it] extinguishes reality for an instant.” The shift of perspective lending different angles to reality is something that Bonomini masterfully captures. As he writes in another story: “Maybe it’s just time, pure time, that makes us see the same things as if they were different.”

There are moments, throughout the collection, where Bonomini grounds the reader in realism; while each story launches the reader into a land of speculative adventure, the metaphysical riddles occur amidst an underlying feeling of relative mundanity. The characters sit at cafes, in apartments, in bed. A man watches a woman at a private fashion show, a seemingly normal event until the clothing eventually reveals an almost infinite series of changes, resulting in a culmination of shows that take nearly a lifetime to watch. Toeing the line between magical realism and lyric, the author remains in conversation with postmodernists of his generation while crafting an utterly distinct voice: one in which Jordan Landsman translates with grace. As grand as the narratives are in theoretical thought, almost all consist of zoomed-in moments during everyday life, and it is in this smallness that the wildest of experiences, and the largest of questions, can feel entirely real.

In telling these tales, Bonomini tends to smudge the line between poetry and prose. “The Singer” is a string of words dragged across four pages, consisting of a single sentence. In this long surge of breathless recollection, the narrator learns of the death of a singer, reveals the powers eventually given those who revealed the news of the death, considers the ambiguity of what it means for an artist to die, and philosophizes on the malleability of memory as radios play the still-vivid voice of a deceased singer—how the music “swept through the house and my house was everyone’s house and listen these are not empty words for good reason it was buenosaires everything that happened happened there even the fig tree and the jasmines.” People emerge, dressed as the singer still, denying death so easily, as if “everything had been a dream and one day he’d return to tell us about the hospital where he’d stayed where they’d healed his burns and fortunately his face was untouched by flames.”

The most revealing (though, in typical Bonomini style, it is also obscured) piece of the collection is perhaps “Theories,” where the protagonist, an unnamed cousin of the character, Jacinta, is overwhelmed by the infinity of theories. While the narrator holds back from ever disclosing these theories—let alone what they pertain to overall—it is made known that they concern figs and melon seeds and hair. The theories are woven in darkness, very difficult to see and describe, but one can surmise their contents through a moment of clarity: “when you’re dreaming, the world you’re dreaming in turns into the place you’re dreaming about,” and when you awake, “everything disappears, because dreams are like theories made of thread.”

It is a testament to this collection’s dizzying, wandering nature that the reader is left to consider: what if this story is true? In that sliver of time it takes to gloss over the small black ink of the justified paragraphs and flip through the thin paper pages, who’s to say that the places you visited didn’t briefly come to life? The narrator questions the theoretical nature of theories, extending an interrogation toward any solid fact. Bonomini’s language dances across the page, manipulating stories in a way that both plays with and subverts typical plot structures. At times, words disappear into narrative, like brushstrokes hiding in a painting. At other times, they surface to the front of the page: the words themselves shining in the spotlight.

The final story, “Index Card,” is a short, melancholy account of an unrecognized, unappreciated writer and “his sole and fervent admirer.” Like this character, Bonomini’s musings have fallen through the cracks of time, meeting the same fate. As such, this translated collection represents a resounding archeological project, resurfacing the writing of a forgotten writer whose work is as powerful and unique as that of his celebrated contemporaries. It is a ghost of a book that haunts and perplexes, enticing each reader in with its mastery of language and craft.

Jordan Spector is a rising senior at Washington University in St. Louis, where he double-majors in English and Communication Design. He is the layout designer for the Spires Literary Magazine, a senior forum editor for the Student Life Newspaper, and the president of the Creative Writing Cafe. More on his writing (and art) can be found on his personal website or on his Instagram.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Yet So Alive: A Collection of Groundbreaking Latin American Horror Stories

- Riveting Banality: On Rebecca Gisler’s About Uncle

- A Guest of Its Originality: An Interview with Ghazouane Arslane