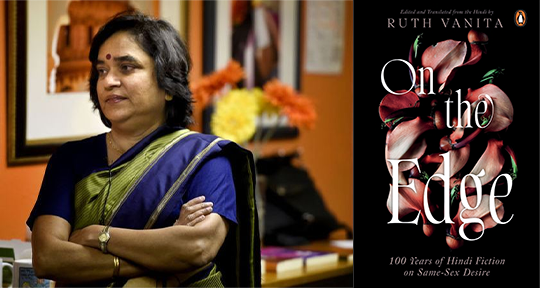

On The Edge by various authors, translated from the Hindi by Ruth Vanita, Penguin Random House India, 2023

“We all live in a prison of some kind,” Manoranjan, the protagonist of Sara Rai’s story “Kagaar Par,” tells his lover Javed, from whom he is separated both by barriers of class and religion, and by the glaring fact of social opposition to same-sex relationships. “Not being able to love openly is my prison. . . I know that it’s very hard for an ordinary man to understand my compulsions and to love a prisoner.” The story’s title, translated as “On The Edge,” lends its name to this anthology of translations from Hindi by Indian author, professor, and activist Ruth Vanita, and echoes the themes of queer desire and alienation that run through the collection.

This book comes amid what the Booker Prize-winning translator Daisy Rockwell has described as a “boomlet” in translations of modern Hindi literature—a boom in comparison to the previous dearth of translations, but one in which “so much remains untranslated and unpublished,” including key modern works. On The Edge, which includes modern and older stories, can in some ways be considered part of this boom, which is highlighting the variety and depth of Hindi literature. The story collection also comes at a time when same-sex relationships in India are under increased scrutiny—the Supreme Court is currently deciding a batch of petitions to expand existing marriage laws to include same-sex marriages—and in this context, it is also an attempt to unearth stories depicting queerness in Hindi literature

In this way, Vanita’s anthology makes a powerful statement against the frequent assertion that homosexuality is an aberration or alien to Indian culture. This view of Hindi literature as devoid of queer stories is a common one. In the introduction to this anthology, Vanita demonstrates how widespread this misreading is, quoting Namvar Singh, a revered Marxist critic of Hindi literature, who described homosexuality as “an exception, not a widespread practice,” and declared that “that is how it should be portrayed in literature.” He also derided authors working in English who, he claimed, were “trying to gain cheap popularity by glorifying this exception,” and cautioned the Hindi literary world against this.

Notwithstanding traditionalist concerns, new and translated works have continued to explore the rich depths of how Hindi literature explores same-sex relationships and queer desire. At the same time, the decision to translate queer literature comes with its own pitfalls—a key one being how to translate words surrounding gender and sexuality from one language to another, and how to make these culturally-rooted means of expression intelligible in English, the language that most often dominates queer discourse in India. Queer expression in Hindi, Urdu, and other Indian languages often resides in ambiguity and metaphor, not because of a need to veil it, but simply because for a long time in India, such relationships were never ‘queer’ in the sense of a deviation from social norms. Accordingly, the words used to describe them could remain ambiguous, free from any need to either highlight or obscure non-heterosexuality. In a public lecture in Bangalore, titled “Translating Gender and Sexuality,” Vanita spoke about how, in translation, some silencing of meaning and nuance is almost inevitable, as certain phrases from Hindi and Urdu are effectively untranslatable, including some that are directly linked to how queerness is expressed and hinted at.

Words describing same-sex relationships, and the rituals that were used to solemnize them, carry cultural significance that is difficult to translate; a particularly evocative example was zanakhi for a female partner, which came from the breast-bone of a bird that was eaten together. Even when these relationships are only being hinted at, the gender-neutral pronouns of Hindi and Urdu allow love songs and poems to be interpreted in ways beyond the heteronormative but it is difficult to translate these deliberately ambiguous pronouns.

This ambiguity can often be a double bind in translation. On the one hand, it makes it easier for queerness to be glimpsed from under the veil of outward heterosexuality. For instance, the 1998 song “Pyaar Kiya Toh Darna Kya” (if one has loved how can they fear), which comes from a movie about a straight couple, is a popular anthem among queer communities in India. Despite its original context, the song is not gendered, and this ambiguity has allowed the song to be used as a means of asserting queerness, for its core message of loving despite fear. At the same time, linguistic ambiguity has also made it easier for queerness to be erased from texts, as in heterosexualised translations of Urdu rekhti poetry, which was originally about women’s same-sex desire. This interplay of assertion and erasure is key to understanding the translation from Hindi of works focusing on gender and sexuality.

While queer themes are becoming more common in literature released in India, many recent works in regional languages, especially those that have been reasonably commercially successful, focus only on gay men—Sachin Kundalkar’s Cobalt Blue and Vasudhendra’s Mohanaswamy, originally written in Marathi and Kannada respectively, are key recent examples. The traditionalist insistence that homosexuality is an imported motif in Indian literature, as well as the recent focus on more marketable queer stories, combine to erase a longer tradition of Hindi writing on non-normative gender and sexuality, much of which focuses on the self-assertion of populations other than urban upper-caste cisgender gay men. It is this tradition that Vanita aims to recover by way of the translations in On The Edge, which represent “100 years of Hindi fiction on same-sex desire,” to quote the subtitle.

The stories play out against a century of rapid social change, from the politics of anti-colonial newspapers in “Discussing Chocolate” by Pandey Bechan Sharma (known by his pen name, Ugra), to the Covid pandemic in “Mrs. Raizada’s Corona Diary” by Kinshuk Gupta. Vanita translates texts by authors known beyond Hindi literary circles, such as Premchand and Geetanjali Shree, as well as others such as Rajkamal Chaudhuri and Vijay Dan Detha, who have been influential on Hindi literature but are not well-known elsewhere, and relative unknowns like Shobhana Bhutani Siddique and Asha Sahay.

A standout in the collection is Vanita’s translation of extracts from Sahay’s Ekakini, which is often seen as the first novel in Hindi focusing on lesbian characters. It was out of print until recently, and Vanita’s translation is the first time extracts from this text have been made available in English. The title, which Vanita chooses not to render in English, roughly translates to “a woman on her own,” but also conveys a subversive anti-patriarchal strength that gets lost in literal translation. While the prose itself is overloaded with obvious symbolism surrounding the meanings of the names of the lovers, Arati (prayer) and Kala (art), it also presents a subtly political depiction of love that flouts patriarchal norms of marriage, gender and domesticity.

In her editorial introduction, Vanita writes that both Ekakini and Geetanjali Shree’s Under Wraps depict “a utopian yearning for a creative world not fully containable in domesticity.” Shree’s novel is told from the perspective of a young boy who is raised by his aunt and her maidservant, long-term lovers whose trysts take place on a rooftop shared by multiple households. They exist both in plain view of the world and hidden by the seeming impossibility of a relationship between two women whom “spectators have seen together yet have never managed to see,” their lives an assertion and an erasure all at once.

This partial or inadequate understanding of non-heterosexual love and identities is key to many stories in the collection; poignantly, some of the more modern stories, such as Madhu Kankaria’s “Lado” and Akanksha Pare’s “Girlfriend/Beloved,” are told from the perspective of family members struggling to understand their relatives’ sexuality. This struggle is often, again, marked by this pattern of assertion and erasure; in “Lado,” the title character’s attempts to assert her sexuality as a lesbian are relentlessly stifled, even after her death by suicide, by her politically connected family. Although there is more knowledge about gay relationships now than in the past, this knowledge is often partial, and there is often still prejudice and fear when family members contemplate one of their own being in a queer relationship. The protagonist of the last story in the collection, Shubham Negi’s “Shadow,” knows that his dates with men are no longer illegal, but that “the script had not yet been invented to write the answers to certain questions. . . Family relationships were like thorns stuck in the feet.”

Thus, in chronicling a century of queer lives in India as refracted through the prism of Hindi literature, the anthology becomes an archive demonstrating how attitudes have changed over time—from the relative openness (albeit in the face of societal and even narratorial disgust) depicted in Ugra’s stories to the gradual erasure and “debilitating invisibility in the post-colonial metropolitan world” that hurts and shields characters like Sara Rai’s Manoranjan, to the delicate negotiations between generations and ideas that occur in the more modern stories, like Negi’s, as queerness gradually becomes more visible and accepted in India.

However, some of the stories in On The Edge seem to have been translated solely for their assertive value and what they say about the historical existence of same-sex desire, rather than being interesting in their own right. The plots, especially of the early stories, are often formulaic, with a tendency towards melodrama. Many rely upon common cliches and stereotypes, especially about women—the Christian woman as a bad influence, the rural girl as sexually unfettered, the unmarried woman as bitter and meddlesome. Amusingly, there is so much repetition of themes and tropes that, in two different stories, the lesbian characters’ potential male love interests have the same name, Harsh. In her introduction, Vanita acknowledges the stereotypical nature of some of the texts and says that she chose them “either due to their close observation of same-sex desire, or because their fiery, no-holds-barred intensity counterbalances the depressing pattern of pretending not to be and not to see.”

On reading the entire anthology, however, the repetitiveness of key themes makes it hard to fully inhabit the worlds of the stories; while in some cases this sense of alienation mirrors the characters’ detachment and isolation from the unaccepting world, at other times the formulaic themes end up making the stories seem contrived. The anthology format does not do these characters justice; by the end, their own detachment and the predictability of the stories combine so that they read like archetypes. To quote a character in Negi’s story, they come to seem like “so many bodies acting” out their assertion of same-sex identity and their relationships’ legitimacy. It is, to a large extent, this assertion of desire from which On The Edge draws its meaning and relevance as a collection—given that, the repetitiveness of the stories and the flatness of the characters through which it is made is a little disappointing, leaving the collection as a whole without the same intensity and feeling that it means to affirm.

Still, the anthology itself is a powerful rebuttal both to the notion of homosexuality as something alien to Indian society and vernacular literature, and to the dominance in overall discourse of certain types of stories focusing on same-sex love. The Hindi word for the act of translation, anuvad, literally means the creation of a subsequent discourse from the original text by making it available in another language. While English does not allow for the linguistic ambiguity that Hindi does, the subject matter of these stories is in itself an assertion of this love in the face of persistent erasure and stigma. The existence of this book as an archive of Indian queer experiences is, thus, an invitation to think further about how same-sex desire and relationships have been depicted and experienced outside of the standard discourses surrounding homosexuality, and about how these stories are influenced by their cultural and historical roots.

Matilde Ribeiro is a law student based in Bangalore, India. She is a copyeditor at Asymptote and has contributed to the blog.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: