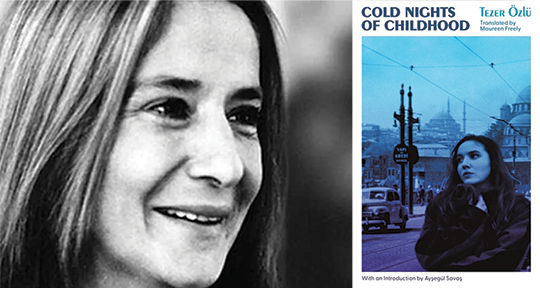

Cold Nights of Childhood by Tezer Özlü, translated from the Turkish by Maureen Freely, Serpent’s Tail/Transit Books, 2023

Known as the melancholy princess of Turkish literature, Tezer Özlü is one of the most influential figures of women’s writing in Turkey. Inspiring generations of writers with both her life and distinct writing voice, Özlü has been a permanent fixture in country’s intellectual history; it’s surprising that such a beloved figure of Turkish literature is debuting in English only now. Fortunately for us, her glaring absence from international publishing has finally been remedied by Serpent’s Tail (UK) and Transit (USA), and English language readers can now discover the genius of a unique writer.

Despite being remembered as a leftist and feminist, Özlü was never a part of the revolutionary struggle like other famous Turkish authors recently translated into English. In Cold Nights of Childhood, she writes: “I was never a part of a revolutionary struggle. Not during the 12 March era, and not after it, either. All I ever wanted was to be free to think and act beyond the tedious limits set by the petit bourgeoisie”. She wasn’t imprisoned or tortured like Sevgi Soysal or involved in organized politics as her close friend Leyla Erbil. Even though she retained leftist sensibilities and occasionally wrote about class struggle, her revolt was more individual and existential. Accordingly, she wrote autobiographical novels which situate readers in the midst of her confrontation with different kinds of authority.

Cold Nights of Childhood is a compact example of her autofiction, and a perfect choice to introduce Özlü to new readers, encapsulating the themes and style that launched her as a tremendous force in the Turkish literary. In the afterward to the novel, translator Maureen Freely writes: “she was one of the very few who broke rules at sentence level, refusing continuity, and slashing narrative logic to evoke in words the things she truly felt and saw, that we all might see them”. Rejecting the linear narrative, she weaves together fragments of time; this experimentation with chronology enables her to reflect on her past while also imagine a way for a gratifying future.

More importantly, Özlü’s sense of time defies, with clear and defined points of reference, the order imposed by patriarchal logos. Growing up in a loveless household where the military and nation were worshipped, she had every reason to be suspicious of such neat stories of deliverance. For Özlü, a single moment contains multitudes: “A single moment can hold an eternity. Can be rich with events and a multiplicity of emotions. Can hold whole mountains, and thick-trunked trees with massive branches”. In her writing, she strives to create this multitudinous nature of time, leaping between memories and emotions. The reader is thus able to picture simultaneously the mature woman reimagining her past and the creative child who was trying to survive in her petit bourgeois context.

Ultimately, this novella can be considered a coming-of-age story where the end point can never be reached. She writes, “No one mentions that life is none other than the days, nights and seasons through which we pass. We wait there waiting for the sign. Preparing. For what? (Now I am living in that future that rushes ever forward. No one is preparing me for anything any more…)”. One can only stop the flow of time by acting purposefully, giving meaning to this process that is life. In fact, for Özlü, writing is the act of carving a boundless existence. There are, however, obstacles that prevent her from self-actualizing—her loveless childhood home, the confinement of family life, her strict Austrian high school, her disappointing marriages, and her recurrent hospitalizations in mental health institutes bar her from joining the abundant life that she knows exists somewhere.

After watching One Flew Over the Cuckoo’s Nest in a movie theater full of strangers, she realizes that she is the only one in the audience to have undergone electric shock treatment. Upon leaving the hospital, she has a hard time adjusting to her happy-go-lucky social circles. In her friends’ world, “the highs and lows are never so extreme. In their world, joy never tips over into madness. In their world, depression doesn’t tip into the fear of death, or the wish for it. They always love to eat. They eat in a measured way”. Özlü, however, wants to live and feel to the fullest. She doesn’t want to repeat the “loveless days and nights” of her parents, worship at the altar of the republic, or pray alongside her nun teachers. Elsewhere, she writes that “living isn’t about going haphazardly through the motions of existence.” It is a tragic irony of history that a writer whose love of life was so passionate should die at a young age of cancer, just six years after the publication of Cold Nights of Childhood.

The novel itself isn’t tragic, however. It is a testimony to the beauty of non-conformism, of struggling to be an individual. The stream of details about her love of Russian literature, life in Paris, French music, German traditions that still remain in streets of Istanbul all render Özlü as an intellectually rich cosmopolitan. She might be locked in hospital rooms and given shock treatments, but her trust in the path she paves for herself never dissolves. After a joyless exchange with a nouveau riche boy, she writes: “How glad I am, not to be cut off from the world, in a trap like his. To be a captive, aging by the day”. Tezer Özlü will never be imprisoned in the traps of bourgeois norms and conventions; in this sense, she is more idealistic than the socialist students she observes on the streets of Bosphorus, who, with time “will become bureaucrats, technocrats, petit bourgeois family men”.

Her novel, however, is by no means an indictment of the leftist movements of Turkey; it is an argument for another type of movement—one that is feminine and sensual. It is difficult to be a woman in Turkey, to live life the way you desire, especially if you, like Tezer Özlü, don’t speak the language of the Father or follow the narrative arc assigned to you at birth. In the last part of the novel, she confirms the preciousness of life once again while observing the Aegean sea. “The beauties of life win,” she writes. Year after year, despite government bans and constant law enforcement hostility, women gather in the streets of Turkish cities to celebrate International Women’s Day on March 8. If this relentless celebration isn’t a testimony to the radical hope Tezer Özlü represented, than nothing is.

Irmak Ertuna Howison is a scholar of literature from Istanbul. She teaches Composition, Philosophy, and World Literature courses at Columbus College of Art and Design. Her publications include academic articles on pedagogical approaches to teaching world literature, feminist crime fiction, and popular books on Jane Austen and Mary Shelley.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: