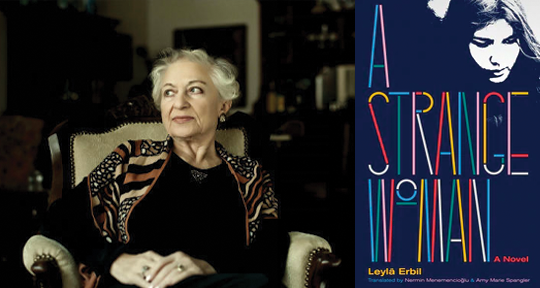

A Strange Woman by Leylâ Erbil, translated from the Turkish by Nermin Menemencioğlu and Amy Marie Spangler, Deep Vellum, 2022

Before jumping to conclusions and judgments stemming from the title of Leylâ Erbil’s debut novel, I consulted Deep Vellum’s take on the book—hoping, or perhaps wishing, that the original Turkish title would give more to go on. Tuhaf Bir Kadın, of which the English title is a direct translation, caused quite a stir in Turkey upon its publication in 1971. Since then, over half a decade has passed—a considerably long time for such a seminal and vital text to appear for the first time in English, by way of Amy Spangler and Nermin Menemencioğlu’s sinuous translation. This is also the first novel by a Turkish woman to ever be nominated for the Nobel, furthering the case for the Anglophone to take notice of this singular author, Leylâ Erbil—or as Amy Marie Spangler calls her, Leylâ Hanım.

A Strange Woman was originally translated by Nermin Menemencioğlu in the early 1970s; herself a scholar and an acclaimed translator of Turkish poetry, Menemencioğlu worked impassionedly to introduce A Strange Woman to a wider audience. However, despite receiving encouraging responses, no publisher was willing to commit. When Amy Marie Spangler stepped in almost half a century later, her contributions to the original translation further advanced the efforts towards publication—although Spangler admits in her preface that “world literature would have been all the richer” if it were published in its original form.

Further complicating the timeline is the fact that over the years, Erbil—in her signature defiance of convention—had “updated” the novel as further editions were released. Spangler worked on incorporating the new passages, only to discover that Erbil had also made additional edits and changes throughout the text. Naturally, these different versions had to be cohered, and one thing led to the other; Spangler found that “the English had been stylistically “smoothed out” in many ways.” The more she put one version against another, the more interventions she made. With both Erbil and Menemencioğlu no longer alive, Spangler and the publisher had to face and continually interrogate the ever-torturing question of how much authority the translator “could justifiably exercise.” She explains:

I decided to attach my name to the translation because the revisions were so substantial that I did not think it right to attribute it only to Menemencioğlu. I did not completely retranslate the book, but neither was the translation Menemencioğlu’s alone. My name, the publisher and I agreed, should be added so that I might bear the brunt of any criticism. I wish only that Erbil and Menemencioğlu were still with us so that we might have collaborated on the text together in real time. […] It seems to me fitting that this translation process was, like its author, rather unconventional.

While A Strange Woman contains autobiographical elements, it’s not necessarily a novel dedicated to remembering. In four parts, the novel narrates the past and present of a Turkish family through the viewpoints of its protagonists: Bayan Nermin, her father, and her mother. It transcribes the coming-of-age of the protagonist—but also in many ways of the country, which, just like Nermin, was trying to understand its relationship to traditionalism. Balancing various voices, the text is unsettling in parts and humourous in others, as in when the stream of consciousness in the second section serves as a historical counterpoint to the still-aspiring present, while the fourth section cruelly exposes the gap between leftist ideals and the actual reality for the ‘people’. Yet, what makes this novel extraordinary is its feminist nature. A Strange Woman was published at a time when the word feminism had not yet entered the Turkish vocabulary and mindset, and as such it was ground-breaking in confronting issues such as virginity, incest, and sexual and physical abuse.

By speaking through Nermin, a young woman and aspiring poet growing up in Istanbul, Erbil vividly conducts us through the cultural and political scenes of the city during the 1960s. We then veer into life as seen through the dying father, Hasan, as he fades back and forth between present lucidity and history, looking back upon his sea-faring days and life, and tracing the narrative along Turkey’s lineage, back to the beginning of the century. Like Erbil’s father, Nermin’s father was a ship captain, and both author and protagonist were also politically engaged leftists of middle-class upbringing. Ranging between Turkey in the 1920s, the leftist efforts, the trials and adventures of a ship captain, and Istanbul in the 60s—the pieces of a larger picture soon begin falling into place, leading into the question, eventually, of who killed Mustafa Suphi.

Erbil continually adjusts her novel by inserting into the third section—“The Father”—newly discovered information about the never-solved “M. Suphi Incident.” Suphi, who founded the Turkish Communist Party (Türkiye Komünist Partisi, or, TKP) in 1920, was assassinated in 1921, together with fourteen Turkish communists and his wife, as they journeyed on a boat towards a meeting with Mustafa Kemal (two years before he became the first president of Turkey). The incident was written off as an ordinary maritime accident, yet Erbil, in her incisive way, pursued the mystery, writing in a long preface of A Strange Woman’s sixth edition: “I have felt it necessary to use some information and documents I have newly become aware of regarding Mustafa Suphi.” Following this, in the prefaces of the seventh edition (2001) and the eight edition (2011), the same short addendum appears (with only the edition number and year changed):

I did not find any new documentation to add to this, the eighth edition of A Strange Woman, printed in 2011. I apologize to my readers if I have missed anything.

The question of Suphi’s killer, however, is not the only question that hangs amidst the narrative like a fog. Even though it’s unclear whether Nermin is even aware of her father’s Communist-adjacent past, the first section (a diaristic installment titled “The Daughter”) follows Nermin’s determination to immerse herself in the creative, anarchist youth culture of Turkey. In doing so, she is regularly thwarted by her complicated relationship to her parents, as well as by members of the old guard, who are wary of Nermin’s turn toward secularism. By the fourth section—“The Woman”—the text is given back into Nermin’s voice, and to her final question, echoing her relationship to class: “Do you love all the people?” With her conflicted character and her genial naiveté, Nermin is manifested in the title.

As Marina Manoukian poignantly stated in her essay on Erbil, “what makes . . . A Strange Woman stand out amongst the cacophony of literary experimentation is the novel’s actualization of its own linguistic exploration not only in form but in content as well.” Perhaps this newness is where the strangeness occurs, but a line in Spangler’s preface caught my attention: “The book’s title has become an epithet for the author herself, whom I would also describe as “strange” in all the term’s myriad shades: unusual, out of place, peculiar, queer, bizarre, perplexing, alien.” In attempting to understand the wide and varied connotations of “tuhaf” in the original Turkish title, Erbil’s work reminded me of the ongoing debates regarding Camus’ true intentions when choosing “étranger” as the title of his masterpiece; in the case of translating Camus, it is still debatable whether “stranger” or “outsider” is more preise. It would be a stretch to think that Erbil meant to portrait Nermin as an interpretation of Camus, yet, in A Strange Woman, she similarly coupled existentialism and absurdism—albeit in her distinct style. Nermin, a female stranger and a strange woman, depicts the existential struggles of the modern individual who clashes with society, with no concrete results to mark her presence or actions. On her own terms, Leylâ Erbil has written a feminist, Turkish text that travels alongside L’Étranger.

Carol Khoury is Editor-at-Large for Palestine at Asymptote, a translator and editor, and the Managing Editor at the Jerusalem Quarterly.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: