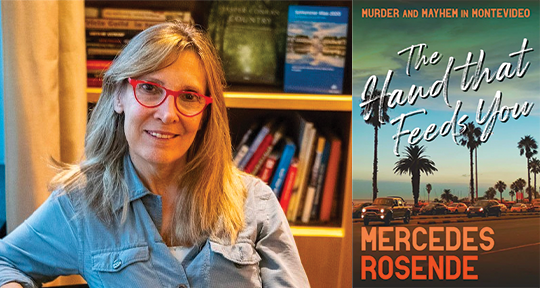

The Hand That Feeds You by Mercedes Rosende, translated from the Uruguayan Spanish by Tim Gutteridge, Bitter Lemon Press, 2023

The Hand That Feeds You is Uruguayan author Mercedes Rosende’s sequel to Crocodile Tears, the thriller that won her the prestigious German literary award LiBeraturpreis in 2019, and it continues the author’s track record of bringing powerful, darkly comic crime novels to her readers. The duo of Rosende and translator Tim Gutteridge work together to fill these pages with characters both strong and deeply flawed—none more so than the protagonist Ursula López—living in the Old Town of Montevideo which, similar to its inhabitants, hides more than it shows.

The high octane beginning nails the reader into their seat in Rosende’s theatre; the narrative feels cinematic throughout, with the author always adept in choosing what to spotlight, what to lampshade, when to pan out, and when to zoom in. The narrator is all-knowing, telling us what is happening and what will happen in the same sentence, but also proves adept at knowing when to let the characters speak for themselves for the benefit of the reader—a mark of Rosende’s command over her prose’s flow. There are many places where the focus shifts from the action to the characters, integral in showing the individual states of mind:

We see her face in close-up: she is flushed, and perspiration is starting to accumulate around her open, smiling mouth. She is lightly made up, just enough to accentuate her beauty. She has taken great care over her clothes, loose black garments that suit her, even if many people, slaves to ideals of beauty imposed by some mysterious criterion, would say she is a few pounds overweight.

The people of The Hand That Feeds You are involved in a bank heist gone wrong, and by writing such vivid personal presences, Rosende allows readers time to catch breath between tense moments, all playing out amidst the backdrop of commentary on society and life in Montevideo—the author’s own hometown. In the crime’s aftermath, the robbers, the cop, and the lawyer who is behind the whole thing become engaged in a game of cat and mouse with Ursula—who drops in at an opportune moment to make away with the money.

The language does not try to override the plot in importance and impact (there isn’t much need for ornate style in a page-turner that has one holding one’s sides and breath in equal measure) but it has peculiarities that again, draw the eye to certain elements that Rosende and Gutteridge want us to focus on. For instance, there is something off about most of the characters that populate the novel. Ursula’s companion Diego, always at the mercy of the people around him and his own fears, “opens his eyes like a ventriloquist’s dummy”; his lawyer, Antinucci, has an unnatural smile and eyes like hard-boiled eggs. Our protagonist Ursula has schizophrenic conversations with her dead father. All these elements lend their characters something unnatural, broken. A touch of the preternatural also hangs over them, be it a haunting, a religion, or a reversion to superstition and a desperation for signs to aid decision-making in moments of stress.

These details are reproduced by Tim Gutteridge for the English reader through the precise choice of single words like “avarice” with the fervently religious Antinucci, or entire passages like: “a place that was the haunt of junkies and homeless people who lived in the doorways of abandoned stores, people who wandered like shadows among ruined houses, who installed themselves in empty buildings or in the cement skeletons of half-built structures.” The underbelly of the people and the town go hand in hand, and Rosende lays them all bare. There’s also a theme of age and exhaustion throughout—none of the characters are brimming with the spring of youth; most of the story takes place in the forgotten parts of Montevideo’s Old Town; and there’s a focus on values and faith, on virtues like patience. Yet, this is very much a modern crime novel, where Dark Web transactions help people cover their tracks, and public announcements mechanically urge civilians to head for the nearest exist when guns are fired in shopping malls.

Despite the gung-ho nature of a violent heist, there isn’t a single, beginning-to-end account of the act itself—even though the timeline is not linear and we revisit the scene more than once. This is astonishing, seeing how the entire book revolves around the people affected directly or indirectly by the incident; the visceral, gripping event only serves as backdrop—like the mentions of unusual weather—never bursting to take centre stage. There are no mere coincidences within the text, however, for Rosende is always in control of what happens on the page, even when days of an Indian summer appear out of nowhere amidst the winter of Montevideo.

The other aspect that stands out in The Hand That Feeds You is its protagonist; Ursula López’s strong will and composure borders on ruthlessness, embodying all that makes this novel a thrilling read. She does not exercise her will by putting weak men in their place, but by conquering her demons and accepting help from those who either care for her, or are interested in the financial incentive she offers. Rosende shows us how in a world full of lies, scandal and deceit, it is hope—and money—that unites us all.

Having gone through tough times and now dealing with the baggage of childhood trauma, she has a desire for change. Right at the beginning of the novel, we see evidence of her inner turmoil and restlessness: “In the apartment where I live, there are sighs in dark corners, creaking floorboards, a cold draught blowing across the kitchen worktops.” She is not propelled by the Garra Charrúa—a vivid tenacity—that Uruguayans (especially soccer athletes) claim resides in them all, but is driven instead by her yearning for something positive. Her glimmer of hope manages to urge her past both literal and metaphorical mountains of dirt and rabble—such as the tunnels in which her and her sister crawls through to escape Antinucci and the thugs, who come after her and the money from the heist. These tunnels serve not only as a claustrophobic realism to the novel, but also reverberates with historical significance: they are the same tunnel the inmates of Puna Carretas Prison escaped from in 1971, an incident that sent great waves throughout Uruguay, as Rosende explains in the epilogue.

While the narrator leads the reader in The Hand That Feeds You, there are no instances where the hold feels forceful or authoritative. You don’t need to swat the voice away to explore this world: “. . . while they enjoy the pause in the conversation, we can look around.” One is happy to maintain that connection, to see a place and its people through the knowing eyes of someone who has been there. The town’s history is amalgamated into the plot, filling in colour between the bold strokes of action. Rosende has always been a champion of writing in her own language—Uruguayan—and about her hometown; in this, The Hand That Feeds You can be read as a dedication to Uruguay, and its perception by both natives and those who have never visited.

Chinmay Rastogi is a writer, translator, and researcher. His work has appeared in Bluestem Magazine, Every Day Fiction and Kitaab, and his translation work is forthcoming in Anuvad. He likes to add colour to the lives of those around him, and can often be found smiling or grumbling under a motorcycle helmet or behind a harmonica.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: