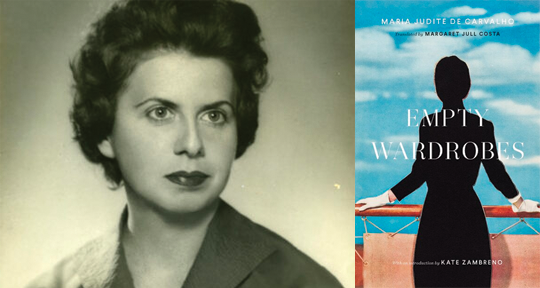

Empty Wardrobes by Maria Judite de Carvalho, translated from the Portuguese by Margaret Jull Costa, Two Lines Press, 2021

The year is 1966. Conservative Portuguese dictator António Salazar is advancing in age. During his thirty-four-year reign, economic policies have failed to fulfill their initial promise, the regime’s supposed “political stability” has stifled the nation, and costly colonial wars have wearied its citizens. The Carnation Revolution, which will end his corporatist Estado Novo with virtually no blood spilled, is still eight years away. Into this climate of looming uncertainty and cautious hope, Maria Judite de Carvalho inserts her simmering novella, Empty Wardrobes, asking impossible questions about the nature of self-determination, ambition, and love. On the eve of a revolution, it dares to doubt whether or not the people will be brave enough to support each other, rather than the powers that be.

Empty Wardrobes sets its existential drama in the domestic sphere. Dora Rosário is a young widow with a daughter, Lisa—young by today’s standards, but “both ageless and hopeless” to the onlooker. She had loved her husband Duarte desperately while he lived, upheld his purity of character, and believed their life together to be a happy one—albeit with some financial troubles.

An egotistical Christ, she used to think; a secular, unbelieving Christ who had only come into the world in order to save himself. But save himself from what, from what hell? She felt no bitterness, though, when she thought all this, only a slight bittersweetness, or a secret sense of contentment because she did love him. He was a good man, a pure man, untouched by the surrounding malice and greed. He remained uncontaminated.

In his death, she devotes herself to his goodness like a nun. Her name, after all, means “rosary”’ and indeed she does seem to be ticking off days like beads. She passes one to get to the next, her mind wholly focused on “the good times”—the happy days of her marriage, which she hopes neither to retrieve nor improve upon.

We come to know Dora as a rather pitiable creature—self-effacing, above all. The precarious period of early widowhood leaves her with the impression that “she and Lisa were on one side, and all the others were on the other side. The others were the enemy from whom she could expect nothing good, only evil.” Isolation and poverty, however, degrade her pride much more easily than the memory of her late husband; ultimately, one cannot live on integrity alone. A lingering acquaintance gets her a job at an antique shop, though her husband had never wanted her to work. She raises Lisa in a bourgeois manner of which he would surely disapprove. There’s an inconsistency between Dora’s idolization of her husband and the actions she takes in order to survive—a paradox analogous to that of her fellow citizens, and of anyone who has been failed by a beloved ideology. An ideology, whether implemented on the national or domestic level, is not necessarily flexible enough to meet the challenges of daily life. Though she may toe the party line in public—and even in private—it’s a less obedient resourcefulness that allows her to prepare her daughter for a more optimistic future.

Once Dora secures the job in the antique shop—or the museum, as Lisa calls it—the two lead an uneventful life until the eve of Lisa’s adulthood. On Lisa’s seventeenth birthday, they host a cheerful party, at which Dora glimpses a modern way of being young both unfamiliar and pleasing to her. Late at night, after the party, Dora’s mother-in-law reveals a secret that shatters Dora’s worldview, setting off a chain of events that all but guarantees a lasting misery for almost all involved.

Dora Rosário is the novella’s protagonist, but she doesn’t tell her own story. The narrator, a mysterious member of her social constellation, accrues definition like someone approaching from the distance, or an eavesdropped conversation in a cafe. Her tantalizing unreliability, too, becomes clearer over time, as she admits to shading in details to which she may not have been privy or may not remember well. The most incredible thing about her, however, is how her very narratorial presence drives the book forward. Dora Rosário’s dreary widowhood, after all, would spark little interest—beautifully penned though it may be—if this third party hadn’t gone to the trouble of telling us about it. Without distracting from the moment at hand, she hints at some great before and after, a crucial climax to which she is arriving.

The day of her transformation was also, she told me later, the day of the conversation about youth. Dora Rosário always categorized days according to their most important events. There had been the day of the late-night conversation with her mother-in-law, the day of the conversation about youth, and there would be the day of the trip to Sintra, the day of the lunch in Cascais, and many others that grew in importance, becoming more important even than the day of her wedding.

She draws just enough attention to herself for us to get a sense of her urgency. She asserts: “I’m not part of this story—if you can call it that—I’m a mere bit-part player of the kind that has not even a generic name, and never will have, not even in any subsequent stories, because we simply lack all dramatic vocation.” How coy. Her dramatic vocation is evident from the first page. As for her naming, she manages to avoid it for over half the book; when she can’t hold back any longer, the event becomes a sort of narratological climax, with its own before and after.

It serves the interests of the men of the story that the women believe themselves to be isolated from one another, much like how it served the interests of Salazar’s regime that the Portuguese only realized after his passing how widespread discontent was across various sectors of society. The cast is overwhelmingly female, and each woman remains focused on her own home and her own family structure, both to their detriment and to the benefit of the men in their lives. Attaching their own desires to those of men, they find themselves repeatedly disappointed. Even though Dora offers her daughter more opportunity and a more expansive image of the future than she had in her youth, she models an ethic of individualism, rather than mutual support, which the novel suggests will be a handicap for Lisa in the future. The missed opportunity to adopt an ethic of solidarity in a crucial moment of possibility reflects the fear leading up to a revolution: that the people might trade one false idol for another, rather than electing to pursue significant change.

Margaret Jull Costa’s translation hits not a single false note. The text has an antique finish without being dated, which is true to the spirit of the book; age and relevance, we learn from Dora, are in no way correlated. Lisa’s youth is both eternal and specific. She may dance to the Beatles and imagine the life of a stewardess to be glamorous, but her beauty, precocity, and irreverence are transcendent. Her first serious admirer is enchanted from their first meeting: “Her thick, luxuriant hair fell like a silken cascade onto her narrow left shoulder, almost reaching her sharp left elbow. . . She closed her eyes, and the light vanished. She was smiling, though, and her smile was also a sight very much worth seeing.” The narrator’s voice is colloquial and familiar, but does not rely on any shorthand (which tends to age badly). Above all, the strangeness of the descriptive voice gives the text a distinctive personality: “Dora was staring, as if fascinated, at her mother-in-law’s head, visible above the pink quilt, complete with makeup, disheveled blonde hair, and pendant earrings. It was as if someone had placed a papier-mâché mask on a pile of bedding.”

Given the elision during the era of Salazar’s Estado Novo between family, faith, and fatherland, it’s entirely appropriate to draw parallels between the domestic and national dramas of the time—to infuse personal devotion with the gravity of faith. In the context of the home, the women of Empty Wardrobes have mastered the bemused, furtive resourcefulness necessary for survival under a failing, oppressive regime, but they each do so privately, valuing the good graces of men over those of other women, whose mutual support would benefit them all. In this way, without sacrificing the intimacy of the domestic portrait, the novella manages to cast the eye of a worried oracle on an entire nation.

Lindsay Semel is an assistant managing editor at Asymptote. She daylights as a farmer in North-Western Galicia and moonlights as a freelance writer and editor.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: