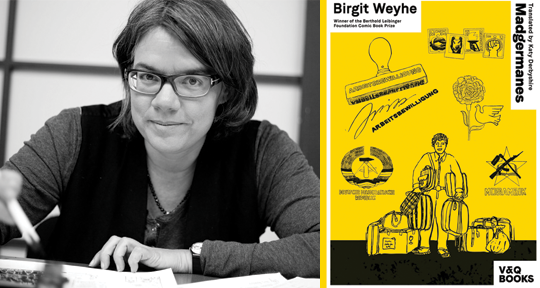

Madgermanes by Birgit Weyhe, translated from the German by Katy Derbyshire, V&Q Books, 2021

The story of the Madgermanes, like that of so many displaced communities, is one likely to disappear into the footnotes of a war’s grand narrative. Having achieved independence from Portugal following the Carnation Revolution, the People’s Republic of Mozambique found itself once again thrown into armed civil conflict during the late 70s. Around the same time, in 1978, the German Democratic Republic sought to combat widespread labour shortages by reaching an agreement with the Marxist Front for the Liberation of Mozambique (FRELIMO), which enabled them to contract workers from their heavily indebted socialist sister state. Spurred on by the spirit of independence and tempted by the education and employment opportunities which were so lacking in their war-ravaged homeland, around 20,000 young Mozambican volunteers left East Africa for East Germany. These volunteers would later be labelled the Madgermanes—a concatenated form of “Made in Germany,” used to taunt and belittle those who later returned to Mozambique after the fall of the Berlin Wall.

Memory is a dog in heat . . . there’s no counting on it.

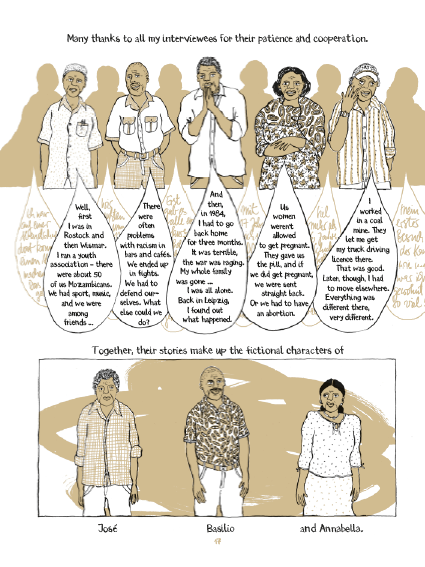

Birgit Weyhe’s Madgermanes is a book of memories. Translated from the original German by Katy Derbyshire, it is infused with all the homesickness, adventure, and exploitation that economic migration entails, hypnotically rendered in black, white, and burnished gold illustrations. Divided into three sections, the graphic novel follows three fictional members of this dislocated community who each recount their experiences, offering a multifaceted perspective on the intricacies of their particular situation, as well as the life-changing repercussions of geopolitics and civil war for the individual. José, quiet and bookish, wants nothing more than to play by the rules of his new German bosses and learn as much as he can, while his roommate, fun-loving Basilio, is more intent on having a good time. Pragmatic Annabella arrives in East Germany three years later than her co-volunteers, driven by the prospect of an education and of sending money home to what remains of her family. She soon becomes aware of the true nature of the volunteer programme when she is assigned a role on the production line of a hot water bottle factory, a far cry from the kind of jobs they were promised.

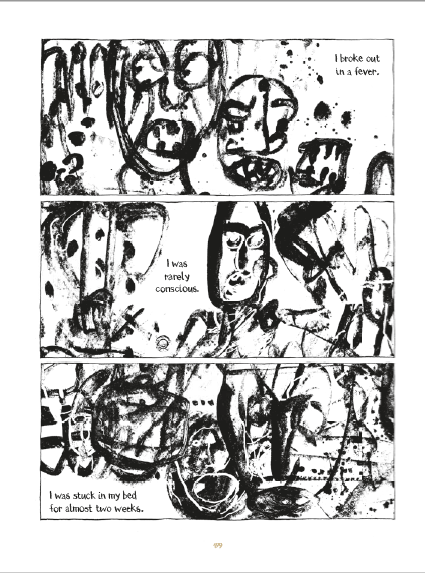

José, Basilio, and Annabella’s memories are as similar as they are different. Upon reaching Europe, they are all faced with racial exclusion, little agency over their place of work, and economic hardship. The latter remains a direct result of the ‘agreement,’ which saw 60% of the workers’ wages retained—wages which are still yet to be received. Each character is painted, textually and graphically, with their own private passions and motivations for migration, as well as the deep sorrows of bereavement and loss. After the fall of the Berlin Wall, each person reacts to increasing hostility and racial discrimination in their own way—faced with the decision of returning to a home they no longer recognise, or attempting to struggle on in hopes of a brighter future in the new Europe. Commendably, Weyhe seems especially committed to underscoring the intersectional nature of the trauma faced by Annabella; hers is the last of the three stories, and it is arguably the most harrowing, visually portraying the entwined struggles of racism, misogyny, and gendered violence with horror-splashed drawings and unflinching honesty. One is reminded of The Unwomanly Face of War, Svetlana Alexievich’s polyphonic masterpiece in which she collects the memories of hundreds of Soviet women who participated in the second world war. Where Alexievich chose to create many voices, Weyhe has chosen to condense the variant struggles into one, though the effect is no less striking. Through Annabella, we can hear echoes of the voices of many other migrant women—forced to choose between their own agency and bodily autonomy in order to protect their own future and their closest kin.

Weyhe’s unique talents as an illustrator are evident in the details she chooses to focus on, employing a range of styles from the more standard western graphic novel structure, to drawings which incorporate East African performative props such as masks and costumes. Full-page scenes depict allegorical situations involving animals to portray a sense of fable-like inevitability, while intangible sensations such as fear and grief are tackled with imaginatively composed abstract forms, which complement the often sparse text. Also notable is the regular inclusion of propaganda art in the form of reproduced stamps and posters, the patriotic optimism of which form a stark contrast against the general lack of solidarity that the Madgermanes come to face on their arrival in East Germany. It gives the novel an almost scrapbook-like feel, a collection of printed ephemera which flash through the scenes as the protagonists reach back through time to retrieve their recollections.

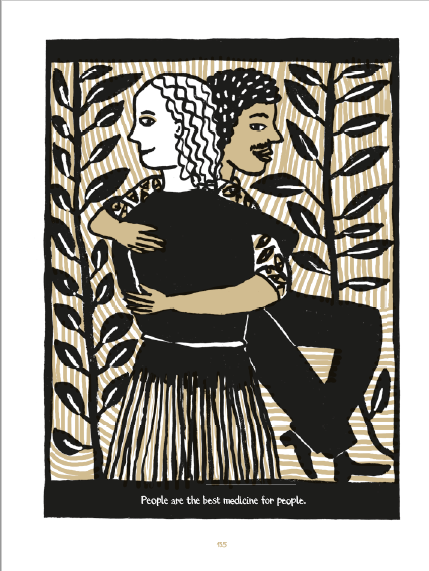

Derbyshire’s translation fits snugly alongside Weyhe’s illustrations, and her ability to infuse concise phrases with such humanity can be exceptionally moving. A full-page illustration of Basilio embracing his lover, accompanied by the phrase, “People are the best remedy for people,” for example, is especially affecting. There are also elements of wry humour in Basilio’s tendency to relentlessly quote African folk phrases, which Derbyshire reproduces deftly. Importantly, the textual and graphic elements slot harmoniously together to transmit the characters’ unique sense of disorientation, as well as the often unconscious desire to identify and recover that elusive concept: home. As Annabella concludes, “Like all other emigrants who have set out for a new life, I belong neither in one country nor the other. We are all without ties, unanchored, floating between cultures. No matter whether we go back or stay.” The reader is left with the sensation that home is not a fixed thing, but something that must be made and remade.

Madgermanes is a work of fiction, but the three stories it relates are based on the lived experience of Mozambicans interviewed personally by Weyhe—a German national who spent her childhood in Uganda and Kenya. Though their accounts are inevitably filtered through the author-illustrator’s gaze, Weyhe’s narrative “I” dissolves in the brief introduction to the book, shifting the focus smoothly onto her subjects. The much discussed issue of speaking on behalf of others in such hybrid works of fiction/non-fiction is a contentious one, and it is challenged further still by the use of illustration to mould the fictional counterparts of Weyhe’s interviewees. In making sure that we know her characters are based on real experiences, Weyhe clearly wants to demonstrate that she has the authority to adopt an “I” that is other, yet limitations of the form prevent a more thorough discussion of ethical dynamics. A useful point of reference in such dilemmas is philosopher Linda Alcoff’s essay “The Problem of Speaking for Others,” in which she writes: “One cannot simply look at the location of the speaker or her credentials to speak, nor can one look merely at the propositional content of the speech; one must also look at where the speech goes and what it does there.” That is, the effect of the speech or text as it echoes out into the world, is as important as its authors and subjects. In transmitting oral histories through fictional first-person narratives, Weyhe uses her skills as a storyteller to ensure that the resounding effect of her work is one of profound empathy.

Though a fascinating story, Madgermanes is also a necessary and timely reminder of the power of multilingualism and translated literature to bring underreported injustices and intercultural exchanges to international attention. The tendency of the global north to generalise African experiences of migration is challenged by interdisciplinary approaches to creative non-fiction such as this book, which can be read as an act of solidarity. Thanks to Weyhe’s and Derbyshire’s efforts, I am certain that other books will be written about the story of the Madgermanes, though I am equally sure that none of them will be quite like this.

Maddy Robinson is a freelance writer, editor, and translator, and is currently studying for an MLitt in Comparative Literature. She is one of Asymptote’s Spanish social media managers.

*****