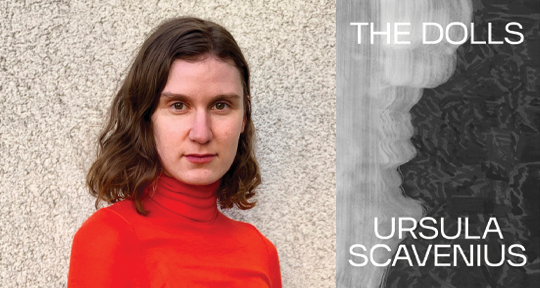

The Dolls by Ursula Scavenius, translated from the Danish by Jennifer Russell, Lolli Editions, 2021

Ursula Scavenius has created an inexplicable environment in The Dolls, a collection of four stories that render the common traditions of narrative into cerebral mystery. Perhaps our characters are in Denmark, but what iteration of Denmark is it? She does not seem to call upon any particular reality or time period in which to place her characters; even the mention of actual years or eras, be they 1888 or 1999, don’t seem to hold much meaning. Amidst this ambiguity, you might say something is rotten in the state of Denmark. The epigraph of the text, deftly translated from the Danish by Jennifer Russell, reads: “I’ll tell the story, even if no one is listening.” While not necessarily a unique sentiment, it aptly sets up a book that comes to us in English translation, which has found itself a new set of readers who are ready to listen.

Fittingly, this book is part of Lolli’s New Scandinavian Literature series—and it does seem to live within that hint of reinvention, avoiding any stereotypically Danish or Scandinavian elements. There’s no hygge—that adulated brand of upper-middle-class coziness—here: everyone is decidedly uncomfortable. Nor can they be categorized under the beloved genre of Nordic noir—no outright crime exists in these stories. Instead, we have paranoia, dread, perhaps some doomsday prep, but no hardboiled investigation or detective work. Although Scavenius may not explicitly belong to the traditions of Scandinavian literature, you could thread her particular type of psychological penetration and sense of displacement with the likes of Clarice Lispector, Wuthering Heights, perhaps Ghost Wall by Sarah Moss or Amparo Dávila’s The Houseguest and Other Stories (translated by Matthew Gleeson and Audrey Harris), taking part in a global narrativization of women who find themselves in archaic or alternative lifestyles, or otherwise alone—either by their own accord or against their will. A timeless situation.

Each of Scavenius’s stories drops the reader directly into the tumult, without providing much backstory or explanation, giving over to the book’s universe. The reader enters directly into the character’s world, and is able to leave just as easily, almost floating through the tales and their various worlds; it’s a bit like The Twilight Zone—the reader simply must accept the current reality until it switches to a new one.

The first story—which shares its title with the collection—reverses the trope of the woman hidden in the attic. Instead, we’re confronted with a girl choosing to hide herself in the basement; in some ways, it recalls the gritty crime shows that proliferate in today’s media landscape, of girls thrown in a cellar or an attic against their will. But what is there to do about the daughter who chooses to stay downstairs, slip notes between the floorboards, and receive a boiled egg once a day? It’s not too much of a stretch to compare this situation to our recent quarantines, wherein we are both being subjected and deciding to stay inside, away from others, receiving our daily food and having some minimal interaction with others. The motivation to hide, to shelter in place, can be attributed to anything: safety, predictability, reliability—the reasons are cloaked in shadow. “The Dolls” leaves you with a simple, haunting feeling—what is enough for a life?

Not to mention that our narrator—the sister of the basement girl—is in a wheelchair with a newly implanted metal shin, rolling herself from the table to the window and back, taking the notes from her sister and dropping her the hard-boiled eggs. Would she join her sister below the floor if she wasn’t in her chair? Would she leave the house, or is she, too, happy to stay inside? Is this something more sinister going on in the house, or is it only in the mind?

The second story, “To Russia: Ermelunden Forrest 1888,” though stamped with a date, does not give many particularities of the nineteenth century. Juxtaposed with the prior narrative of two girls who don’t go very far, this tale focuses on a man who is running away. He leaves his wife and daughter behind, ending up at his long-lost sister’s house. The close proximity of the two stories insinuates automatically the commentary of men’s mobility and women’s stasis or abandonment—behind, upstairs, below the floor, at home. Scavenius capitalizes here on the themes of identity, interpersonal relationships, new and old homes, new and old selves, and getting lost and belonging. The man’s sister, who lives still in their childhood home, doesn’t seem to recognize him, but nevertheless offers him domestic safety out of the simple kindness of her heart. She houses him, feeds him, doesn’t let on. Then, she takes off to Russia, which had originally been his plan all along—leaving him stuck at the house, and finally revealing that she knew who he was the whole time. It’s a delicious turn of events. The note she leaves for him says “I’ve gone on ahead.” This word choice seems important—being one step in front, taking advantage when opportunity strikes.

The last two stories also capitalize on the themes of safety and home. Characters seek refuge, whether in the form of a physical roof over their heads for the night, or the more symbolic and heavyweight return to a country from which their ancestors were once exiled, to bury a dead mother who may or may not be a hero. In “Compartment,” the children question heavily where their mother’s coffin belongs, all within the physical confines of a train compartment, while at the same time speeding along across country lines.

Some of the best writing in the book appears in the form of descriptions that work to build setting and character rather than move along some of the absurd plotlines. Lines such as “His eyelashes flutter like the tails of cows swatting flies in the summer heat” give us a taste of the Scandinavian pastoral landscape where these stories supposedly take place. “There’s an artichoke leaf stuck in my throat and I am trying not to listen” is such a specific and detailed thought, spelled out before us so as to not be ignored. Rarely do we get insight into what others are trying not to think about or do. These details slow down the otherwise sparse prose, calling attention to themselves. And much of the writing is quite visceral, like nails on a chalkboard:

It’s as if those violins are inside my head, says Father and passes Mother the saltshaker. Mother sprinkles salt on her food and stares out the window. The sound of violins from the forest grows louder. When chicken bones scrape against your teeth, it screeches in your ears. The violin bows gnaw at the strings the same way we gnaw at chicken bones. Violins, we keep calling them, but really it sounds like something else. Like chicken bones scraping against teeth.

Scavenius’s book is filled with impressive observation and uncomfortable characters, all bound together by her peculiar and gritty prose, beautifully told in Russell’s immaculate translation.

Sabrina Parker Greene is an assistant editor for fiction at Asymptote. She also reads for the Kenyon Review’s seasonal contest in nonfiction. She holds a degree in English with credentials in French, creative writing, and art history from Kenyon College and lives in Brooklyn.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: