Cuíer: Queer Brazil, translated from the Portuguese, Two Lines Press, 2021

Can we translate “queer”?

Cuíer: Queer Brazil—a brand-new anthology of queer/cuíer Brazilian poetry, fiction, and non-fiction translated from Portuguese into English—wants us to grapple with this conundrum. Uniting voices across generations, genders, and mediums, the latest offering from Two Lines Press’ chic Calico series is, like all its predecessors, expansively and thoughtfully curated.

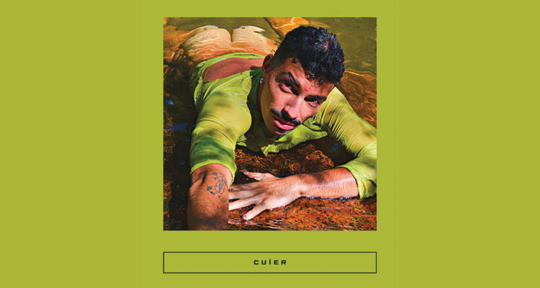

A vibrant portrait by Igor Furtado graces the cover; in it, we glimpse a masc-identified person lying in prone position—one could say amphibiously—on what appears to be the earth of a river bank. His lime-green skin-tight top accentuates the exposure of his body’s lower half, boldly visible in the background through spangles of rippling water. The tattoo on his arm, the earring basking in shadow, the painted nails of his splayed fingers. His direct gaze at the camera mingles enticement and challenge in equal measure.

Like the photograph, Cuíer gives us pause and proclaims its own foreignness—only on its terms are we invited into its gambit. As the only Calico title so far with a non-English word as its name, “Cuíer” demands to be sounded, savoured on the tongue—it audibly carries the phonetic ghost of “queer,” but must be shaped differently in the mouth. The word ostensibly stems from Tatiana Nascimento’s avant-garde “cuíer paradiso,” a poem in Cuíer wherein parentheses, wordplay, and dialect wreath around a yearning for the simple pleasures of quotidian love. What unfolds is an enumeration of possible “less than”s: “less bureaucratic than / marriage equality regulated by the state,” “less surveilled than e-v-e-r-y-b-o-d-y / asking if it is (non-)exclusive,” “less of all that makes us listless.”

In the absence of utopia, one can only imagine it in terms of what it is not (yet). Nascimento’s Afro-futurist linguistic experiments—near the book’s centerpiece—perhaps gesture to the impulse behind Cuíer’s formation: to know another “with no need for armor, / anticipating no answer, / no need to learn how to punch nor / map the space before entering.” A place of silence beyond translation.

Many of the other poems, searching for their own lexicon, similarly bend and twist the Portuguese language without compunction. The translators have valiantly captured the transgressive spirit of these contortions: see Johnny Lorenz’s “beg-end” (a Franken-construction of “begin,” “end,” and “beg”) in Marcio Junquiera’s “saturday,” or Hilary Kaplan and Chris Daniels’ “woe-man” in Angélica Freitas’ “A Clean Woman.”

Still, sometimes one is left with the speechlessness of bodies. “We had no words,” declares the narrator in Caio Fernando Abreu’s “Fat Tuesday” (translated fluidly by Bruna Dantas Lobato), condensing the intensities of a celebratory, writhing night into a blow-by-blow account of burgeoning desire. “I was just a body that happened to be masculine enjoying another body, his, that happened to be masculine too.” Yet, the sanctuary is only ever grasped at, the fantasy shattered by a world that cannot countenance the presence of queer joy even in the midst of revelry and masquerade. A lusciously erotic image of the dancer’s mouth as “a ripe fig cut into quarters” overstays its welcome and, colliding with homophobic violence, mutates into “the slow fall of an overripe fig.”

The collection also touches on transphobia, as in Raimundo Neto’s “Lalinha’s Auntie” (beautifully translated by Adrian Minckley)—less laden with despair compared to the more canonical fiction of Abreu, and almost buoyant with faith in the possibility of survival and kinship. After her Auntie is verbally assaulted by “men with their stares driving daggers into [her] neck,” Lalinha comforts and reaffirms her, reminding Auntie of who she is in the eyes of those that matter. But beyond the vulnerability of Auntie’s body in the world, Neto’s story is concerned with how it can heal, become more self-possessed, anchor itself in the relationship of communion and nurturance that Auntie shares with Lalinha:

Lalinha feeling the continuous shifts in Auntie’s body, from zero to sixty, as she would say, from no one to just someone else, as she would sometimes sob, all in the touch, in the layer of care when Auntie’s skin would meet the girl’s to say Don’t let anyone go here, here, here, here, the finger pointing almost from a distance at the girl’s fruits that in Auntie had already become wounds and an almost-rotting past, that in Auntie were now purple tension and dead flesh.

Neto’s sinuous writing—a standout in Cuíer—mimics those “continuous shifts” of a body with the liquidity of its cadences, its disarming sincerity, its seamless embedding of daily speech in its midst. The other story of his, “The Harvest Bride,” similarly renounces well-worn tropes of narrow-minded parents policing their children’s gender expression. Neto treads the fine line of dealing matter-of-factly with the protagonist’s experience of being shoehorned at school into gender binaries, without trivialising the pain. But what fuels the tale forward is a groping for recognition. “Boy? Who knows. ( . . . ) Son? Who knows.” Words might no longer suffice, as a mother relearns what she thought she knew about her child.

“The characters wear disguises, overcoats, masked faces; all of them lie and want to be deluded. They desire desperately,” reads a letter from Brazil in Ana Cristina César’s hybrid-genre “Kid Gloves” (translated by Elisa Wouk Almino). Or, from Cristina Judar’s “Toward the Earth That Will Remain” (translated by Lara Norgaard): “To no longer be what you are,” in “this dying that is the most living thing of all.” These pronouncements or diagnoses could apply to any number of works in Cuíer. Dissimulation, sometimes born of necessity, and at other times signalling a potential for ceaseless transformation, is rife in this anthology’s snapshots of queer/cuíer Brazilian existence, the untraversable décalage between body and language and time.

But elsewhere, margins of freedom open up, unexpected. Two boys explore each other’s pubescent bodies in the hallway of a dental clinic in the kaleidoscopic time of João Gilberto Noll’s “Hugs and Cuddles” (translated by Edgar Garbelotto). Quietened by the fear of being found out, they experience a “feeling somewhere between enjoyment and its immediate denial”; every sensation of pleasure is shadowed by the anticipation of incipient guilt.

We would bury it inside of us, each day a little more, until we were adults, when the image of the fight on the cold ground would be so crumbled we’d never be able to fully recollect the pieces. We would become a tomb in order to bury the toy we had created in each other’s bodies.

Shuttling across eras of the narrator’s life and circling back to dwell on particular sensory details, Noll’s deft temporal manipulations conjure an air of elegy and longing. As a masseur later on in life, the narrator finds himself transported back to the chiaroscuro of that corridor. Yet the innocence, malleability, and intensity he mourns were perhaps always slightly out of reach—on the brink of vanishing. In Noll’s filmic circuits of memory, so vividly conveyed to us by Garbelotto, I sense the tones of Garth Greenwell, Frank Bidart, perhaps even Ocean Vuong.

Other stories are slower to give away their secrets. Speaking from a place of diaspora or exile, the narrators in Carol Bensimon’s “A New House” (translated by Zoë Perry and Julia Sanches) and Cidinha da Silva’s “Farrina” (translated by JP Gritton) don’t read as straightforwardly queer/cuíer. But they are made to feel their otherness by virtue of being Brazilian in the multiply alienating environs of the United States.

In Bensimon, the narrator works as a sort of English-to-Portuguese translator for insurance companies. Smuggled into the deadpan, sometimes sardonic and offbeat rhythms of these sentences are smart, oblique remarks about indigeneity, immigration, and imperialism in America. One of the characters says to her: “You’ve got an MA in linguistics? Wow.” As if someone who looks the way she does couldn’t possibly be that educated. On a call with her mum, she complains, “I don’t see the sense in moving to a First World country only to make friends with such primitive people.”

Da Silva’s narrator encounters the titular Farrina, a Trinidadian woman in New York, with whose dreadlocks she feels a sense of “kinship among Black folks.” After dropping an allusion to Audre Lorde, she wonders if Farrina is “one of those old-school lesbica who liked to play everything close to the chest,” or “one of those gals for whom every gesture was a rune to be decoded.”

The story, not without a certain coyness, stops just short of satisfying our curiosity—a kind of Patricia Highsmith lesbian romance manqué. There’s nonetheless something poignant and irreducible about these unresolved interactions that testifies to Cuíer’s eclecticism; it will not deign to explain itself to us, if it does not want to.

And this quality might well characterise all of the books in Two Lines’ Calico series, but I find it especially apt here—in the lives of people for whom mystery might be a form of survival. Each piece, with no biographical introduction, greets us with its name, author and translator. How refreshing to meet all of them as they are, without preconceptions or labels. Only at the end of the book do we learn—confirming what we will have intimated—that the writers’ backgrounds span places as varied as Rio de Janeiro, Brasília, and the Brazilian Northeast.

It is certainly not the intention of Cuíer that we, as readers, should emerge from it presuming a greater knowledge of Brazil in a sweeping national sense, with all its diverse subcultures, aesthetics and cosmologies. Given the ease with which queerness can be (and has been) co-opted for nationalist purposes, I wonder, too, about communities for whom the nation-state is not a meaningful point of identification. How much would they be a part of queer/cuíer Brazil? What alternative paradises could they dream of?

At a recent book launch event organised by Books Are Magic, the translator Natalia Affonso said, “We have the right to opacity. Not everything has to be revealed, or literal, or given, or explained.” Bruna Dantas Lobato added, “It is important to think about queerness as not always translatable, and that shouldn’t always be translated.”

The light that words can shed on individual lives is partial at most. Ricardo Domeneck’s “Shyness in linen” (translated by Chris Daniels), which appropriately concludes the collection, knows this—“isn’t it so lovely / how the light itself hides us?”

Alex Tan is a writer, aspiring translator, and student of comparative literature at Columbia University, with a particular interest in the literatures and language politics of Southeast Asia and the Maghreb. They currently work with Transformative Justice Collective in Singapore, and serve as Assistant Editor (Fiction) at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: