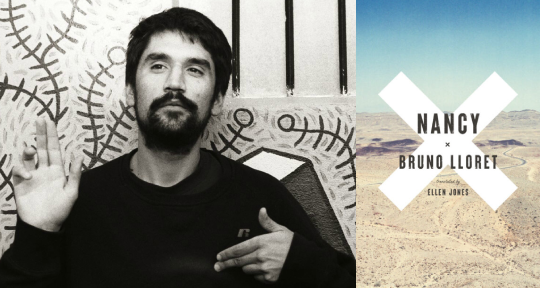

Nancy by Bruno Lloret, translated from Spanish by Ellen Jones, Two Lines Press, 2021

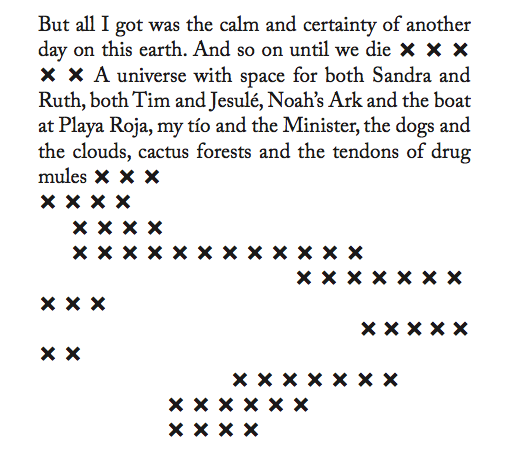

Death haunts the pages of Nancy, Chilean author Bruno Lloret’s 2015 debut. When we meet her, the eponymous heroine is dying of cancer, a painful end to a painful life. The novel—structured as a series of recollections with verses from the Old Testament prefacing most chapters—is written sparely, subdued in tone if not in depth of feeling. Scattered across each page are bold X’s, a mark of punctuation that carries more weight than the period. They don’t impair comprehension of the narrative but rather cast a subtle shadow, calling to mind a graveyard of nameless crosses, or marks on a map—death as the ultimate destination. The first and final pages of the novel feature these marks in a half-hourglass and hourglass pattern, and the shape of each individual X, as they stalk the story and linger between thoughts, echoes the notion of convergence and divergence, time left and time lost. (For a sense of how the marks function in the text, read an excerpt of Nancy in Words Without Borders.)

For Nancy, the point of convergence—the moment of irretrievable loss from which everything then diverges—is when her brother goes missing. Nancy’s childhood in northern Chile, in a coastal town between the desert and the sea, has not been happy. Her mother resents her existence, and Nancy’s girlhood becomes carefully choreographed to avoid inevitable blame and brutal abuse. Her older brother, Pato, is an ally, a friend, a “superhero.” When Nancy turns fourteen, he leaves home to find work at the port in a nearby city. Two years later, he disappears outside a nightclub.

Nancy’s troubles neither begin nor end with Pato’s disappearance, but the family’s grief and misery seem to radiate from this point. The loss doesn’t have the finality of death, and Nancy and her parents find various ways to cope with the pain of knowing he’s gone, but not knowing where. Her mom flees to the port city, ostensibly to look for Pato, and finds instead a way out of her old life and into an abusive relationship. Back in Ch, Nancy and her dad quietly care for each other, Nancy assuming the role of homemaker while her dad works. When he eventually loses his job, he finds solace in Mormonism as the life he built collapses around him—and Nancy.

Nancy heralds a future-facing vanguard in Chilean letters (the novel is set a few years in the future, and Lloret doesn’t overtly grapple with the legacy of Chile’s dictatorship) and, despite its deep local roots, belongs to a burgeoning international literature of shared crises. Born in 1990, Lloret belongs to a generation that must confront rampant environmental destruction and the climate crisis, and contemporary fiction has increasingly taken on apocalyptic motifs. (See, for example, Ling Ma’s 2018 novel Severance, which takes place during a society-shattering pandemic.) Nancy is not an apocalypse novel, but the environment characterizes the narrative to a striking extent in this story of one northern Chilean woman’s life.

The beach is a site of comfort and beauty as she confronts Pato’s disappearance among the dogs and seagulls, but it’s also a site of danger; women go missing along the shoreline, and Nancy finds herself in a shady arrangement with a group of simultaneously sinister and awkward foreigners, who film Nancy and her friends frolicking naked on the beach. Off the coast, a wrecked boat rusts. Chilean industries—fishing, mining, and manufacturing—loom large, as does the suffering they visit upon the poor people who fuel them. With its environmental and economic undertones and biblical overtones, the book hints at an impending reckoning and flirts with more than one notion of apocalypse.

Nancy eventually follows her father into the Church of Jesus Christ of Latter-Day Saints, less because she feels the “siren call of the Word,” as he did, and more to cement a relationship with her father. She hopes after her baptism that he’ll tell her how proud he was.

Ellen Jones makes this difficult translation look easy—in one standout case, rendering the extremely local and abbreviated dialect of one character, Jesulé, in a compact, slangy English that successfully communicates the unique relationship he shares with Nancy. She also smartly retains many Spanish phrases, which chart the interpersonal relationships—mija, tío, papá santo—and anchor the story in Chile. She also worked closely with her editor at Giramondo, the book’s Australian publisher, to maintain the unusual formatting. Many of the X’s had to be rearranged and carefully composed to maintain pacing and impact, and the result demonstrates how the translator’s role goes far beyond linguistic equivalence: Jones’ skill extends from the language all the way down to this deliberate, fraught punctuation.

Like Hanya Yanagihara’s 2015 novel A Little Life, which also chronicles a harrowing series of events on an individual scale, Nancy describes a level of tragedy that verges on unbelievable. While many of Nancy’s misfortunes arise organically, strung together by the narrative, others feel somewhat random and unnecessarily excessive (did she really need to have cancer?). In that sense, it’s helpful to read Nancy with a wide lens. This story of a woman is also the story of a people and a place (mining and arsenic contamination put northern Chileans at high risk of lung, bladder, and skin cancers). This broader scope also provides an interesting perspective on Lloret’s choice to write a novel that revolves in large part around women’s experience of sexuality and violence from his masculine vantage point.

Even as they visually interrupt the narrative, the X’s on every page contribute to a deliberate pacing, both swift and pensive, that makes for quick read with plenty of room to reflect. In the forced pauses—the deep, still pools in Nancy’s stream of consciousness—you can almost hear her stop to catch her breath or look out a dusty window as she gathers her thoughts.

Knowing you’re going to die is horrible not just because you don’t want to die, but also because there’s always some residual, surviving doubt. It survived in me alright, a fledgling hope, hiding behind the eyes. Even though I was skeletal, mutilated, barren . . .

The silences offer Nancy the opportunity to reflect on where she’s been, as she learns to let go. They offer us an opportunity to reflect on where we’re going, as we learn to hold on.

Allison Braden is Asymptote’s assistant blog editor.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: