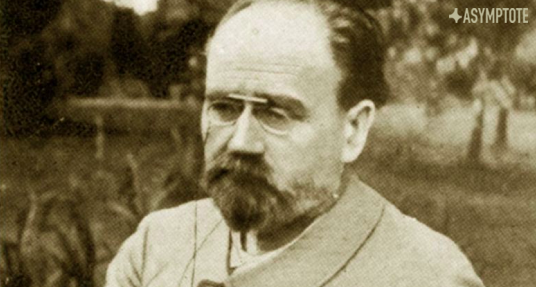

Émile Zola, master of nineteenth-century naturalism, was revered by most but reviled by some: his unflinching account of social decadence during the Second Empire didn’t sit well with France’s more puritan neighbors across the Channel. For decades, English translations of his Rougon-Macquart cycle were bowdlerized in the name of good morals, depriving readers of the full scope and weight of his social critique. Over twenty-five years ago, one of Britain’s most reputable publishers began to make amends, and it has recently completed the mammoth task of fully and faithfully translating Zola’s famed cycle into English. In this incisive historical essay, former Communications Director Samuel Kahler walks us through what was lost to undue censorship, and why it’s such a joy to get it back.

Fans of French literature, it’s time to read and be merry! With the recent publication of Doctor Pascal by Oxford University Press, those at work on new English translations of Émile Zola’s Rougon-Macquart cycle have at last—after more than a quarter century—completed their epic and honorable task. For the very first time, anglophone readers may fully appreciate the scope and vision of the twenty-part masterpiece as its author intended it.

During his lifetime, Zola enjoyed widespread popularity in France and abroad (wherever translations of his novels, stories, and plays were available); he was viewed as the standard-bearer for a groundbreaking style of literary naturalism that presented an unflinching, often critical view of society through its portrayal of vice and corruption across all strata.

The clearest examples of this approach are found in the novels that comprise Les Rougon-Macquart. Similar in certain ways to Honoré de Balzac’s earlier La Comédie Humaine—a compendium of novels which were grouped together and sorted by theme—Zola’s cycle differs crucially in its design: it follows the members of one family rather than miscellaneous characters, and it was purposely conceived by its author from the onset (he initially planned a series of ten works, but soon expanded its scope). Inspired by breakthroughs in psychology and theories of heredity, it was further fueled by Zola’s desire to candidly portray life during his time.

The opening novel, The Fortune of the Rougons, makes no subtle hints about the author’s ambitions for the larger project. By weaving the family’s origin story into a larger plot, Zola announces to readers that the Rougon-Macquarts are not just a family; they serve more broadly as avatars for the passions and qualities of the era. His preface to the work states that “the dramas of their individual lives tell the story of the Second Empire, from the ambush of the coup d’état to the betrayal of Sedan” (indeed, the cycle’s subtitle is Natural and social history of a family under the Second Empire).

The Rougon-Macquarts are by and large—though not universally—a cutthroat clan of dreamers and schemers who stubbornly pursue grand ambitions, short-sighted affairs, and noble sufferings. When their passions lead them down dangerous paths, they do not stray or turn back; that would seem to be against their nature. Their behavior is part and parcel of Zola’s vision, which he delivers through vivid portraits of their interior and exterior landscapes, warts and all; he shows no prudery in depicting their immoral thoughts and acts.

But Zola’s intention was not simply to titillate audiences with sketches of naughty pleasures, bitter rivalries, and lavish excesses. Though the novels may foreground a mad rush of egos and appetites, the theme of nature’s cycles undergirds them; indeed, this theme frames the entire corpus. The subtleties of Zola’s overarching vision, however, did not make a strong enough impression on those who viewed his novels as cheaply sensational and injurious to society’s moral wellbeing. Many thought his works vile and opposed their publication, especially in England.

When Englishman Henry Vizetelly began acquiring and publishing Zola translations in 1884, he sought to boost sales by appealing to the tastes of a mass audience of readers eager for renowned new literature from abroad (the most well-educated among them could already enjoy Zola’s prose in the original French). Aware of England’s conservative stance on freedom of speech in works of literature, Vizetelly and his associates often made their own excisions to the translated texts, in order to avoid fines or legal trouble. As the books appeared in more heavily bowdlerized versions, they lost much of their force in the name of good taste.

This is glaringly apparent in works such as L’Argent (translated as Money), which suffers from the removal of a key plot point, yielding many subsequent inaccuracies that the Oxford translation thankfully fixes. The core story follows Saccard, a risk-taking financier, as he attempts to eclipse the wealth of his rivals while navigating his romantic options and evading the debts and demons of his younger days. He lives with a widow, Madame Caroline, and her brother, who leads expeditions for Saccard’s company. As Madame Caroline develops feelings for Saccard, her heart is tested by the revelation that he once committed statutory rape—a crime which he paid to hush up; it resulted in a child, Victor, now fifteen and living in squalor.

Some of this is conveyed by Vizetelly. His version vaguely states that “there were some abominable circumstances in connection with the affair, but the girl’s mother, consenting to silence, had merely required that the evil-doer should pay her.” The Oxford version, however, reflects the gravity and torment of the entire scenario much more poignantly. Until its publication in 2014, English readers would have had no idea that Rosalie, the victim, was sixteen at the time, or that Saccard “had proved so amorous that poor Rosalie, pushed back too eagerly against the edge of one of the steps, ha[d] suffered a dislocated shoulder”; nor would they have understood the heightened emotional pitch of the “frightful scene, in spite of the tears of the girl who admitted that she had been quite willing, that it was just an accident, and she would be too miserable if the gentleman was sent to prison.” Likewise, they would have missed a particularly ribald passage of several hundred words detailing a man spying on Saccard as he receives oral sex from the man’s own mistress.

More significantly, they would have lacked the many references to poverty’s physical and emotional toll—especially the horrors of alcoholism, the impact of poor hygiene, and the ever-present threat of sexual violence facing poor young women. Gone, too, was Zola’s look at Victor’s life in squalor before Madame Caroline secretly arranges his transfer to a charity home, or the brutal assault he commits before fleeing, never to be heard from again. Aside from blunting the shock of such passages, the censored version of the text hampers the impact of the goodness modeled by Madame Caroline. In her virtue, as expressed through her love for her brother and Saccard, the novel achieves a serene emotional foundation that steadies the story in contrast to the harsh extremes of Saccard’s ambitions. Many, if not all, of Vizetelly’s translations bear these unfortunate marks of censorship, which more broadly detract from the impact of Zola’s naturalism and his integrity in telling the truth about the society he depicts.

To make matters worse, Vizetelly’s efforts to tone down the novels were ultimately in vain: they did not shield him from legal consequences. By 1888, a campaign had been waged against him, with one writer declaring him “the chief culprit in the spread of pernicious literature,” and another saying of Zola’s works that “nothing more diabolical had ever been written by the pen of man; they were only fit for swine, and those who read them must turn their minds into cesspools.” A court summons quickly materialized, and the matter of Vizetelly’s role in disseminating supposedly obscene works of fiction was taken up by governmental authorities. He was sentenced to pay a fine, and several of his Zola translations were removed from the market. As his son Ernest recounts, “though the books were absolutely withdrawn for a time, it was decided to put them on the market again after they had been adequately expurgated . . . [Vizetelly] spent two months on the work and deleted or modified three hundred and twenty-five pages of the fifteen volumes handed to him.” The crusade against the editor resumed, however, and he found himself in court again. This time, he pled guilty and was convicted and sentenced to prison for three months. In the aftermath, he liquidated his business, no longer interested in suffering in the name of great literature.

Most subsequent efforts to translate Zola into English have been inconsistent, and readers throughout the past century have missed out on the complete picture. While uncensored translations of the author’s major works have appeared since the 1880s, others haven’t been translated since the 1890s—until now, that is. As a result, most English-speaking readers are familiar with one or two of Zola’s works, but they are largely oblivious to his corpus. How many can name-check Germinal but aren’t aware of its place in the Rougon-Macquart cycle? At long last, with the publication of Doctor Pascal, an uncensored version of the entire series is available to anglophone readers, who will be afforded all the riches contained therein. Thus, as the work of the Oxford University Press team ends, a new era begins.

Samuel Kahler is a playwright and writer, as well as the former communications director at Asymptote. He lives in New York City.

*****

Read more from the Asymptote blog: