Meseország mindenkié (Wonderland Belongs to Everyone) is a Hungarian collection of classic fairy tales, adapted and retold with characters from minority or marginalised groups. Yet since its release in September, it has caused astonishing controversy and rebuke from far-right politicians, including MP Dóra Dúró literally destructing a copy. Such opposition is propagating intolerance and homophobia—the antithesis of the book’s inclusive and accepting values. Despite such an alarming reaction, the publisher sold out of its first print run. But the threat of censorship still looms large. In this essay, Jozefina Komporaly explores the political circumstances that have created such hostility, as well as the book’s valuable contribution to Hungarian children’s literature.

The publication of a new volume of tales for children is usually exciting news for early readers and their families, for anyone young at heart, and for those following trends in children’s literature. It is also likely to be relevant to schools and nurseries, but it is rarely breaking news. If discussed in the media at all, it tends to belong to the realm of children’s programmes or cultural platforms. In recent weeks, however, this rule of thumb has been overturned in Hungary, where the subject of unconventional books addressed to young readers has sparked not only heated debates, but deplorable reactions from politicians and public figures.

The first time I heard about these incidents, in September 2020, was via a Facebook post alerting me to Hungarian MP Dóra Dúró tearing up the children’s book Meseország mindenkié (Wonderland Belongs to Everyone) and literally putting it through the shredder. She allegedly could not bear to see wonderland turn into a land of “the aberrant.” Dúró is a member of Mi Hazánk Mozgalom (Our Homeland Movement), a far-right satellite party of the ruling Fidesz, and news of her intervention came from her own social media presence when she boasted about destroying the book during an online press conference. According to her, “homosexual princes are not part of Hungarian culture,” and her aim was to lash out against “homosexual propaganda” that she saw as an attack against the “healthy development of children and against Hungarian culture.” The politician ended her Facebook post, hastily removed in the wake of the emergent scandal, with the invitation “to lay the foundations of the nation’s future within the context Hungarian families.” In doing so, she is perpetuating conservative notions about what constitutes a family and explicitly problematizing the relationship between nationality, patriotism, and sexual orientation.

Following Dúró’s incitement, Hungarian mass media and social platforms went into overdrive to discuss the matter, and an unprecedented number of high profile public figures took a stance against the book. Those who spoke out included numerous politicians, but also specialists in the humanities and the social sciences, such as eminent psychologist, psychiatrist, and academic Emőke Bagdy. Bagdy generated further shock waves when he also firmly condemned the publication, thus endorsing Dúró’s act. Emboldened by such support, this wave of rudimentary censorship continued with party activists boycotting public readings, displaying defamatory posters at bookshops selling the title, and with Dúró literally ripping apart another children’s book. Vagánybagoly és a harmadik Á, avagy mindenki lehet más (Cool Owl and the Third A, or Everybody Is Entitled to be Different) was published in 2019, but it ended up on the receiving end of Dúró’s rage simply because its author, Zsófia Bán, had previously delivered a speech at the opening of Budapest Pride. Judging by the nature of such interventions, it is probable that most commentators haven’t actually read either of these books. Their reactions were simply spurred by a fear of anything new, paired with ignorance and intolerance that is deeply engrained in Hungarian society and further exacerbated by the current regime in power. Homophobia, sanctioned by high-ranking politicians such as the current Speaker of the National Assembly, is on an alarming rise in present-day Hungary, and being associated with the LGBTQ+ cause is seemingly sufficient grounds for anyone to find themselves in the firing line of the so-called ‘morality police.’ In response to the controversy surrounding the book, Prime Minister Viktor Orbán notoriously declared that Hungary is tolerant to homosexuality, but “there is a red line that cannot be crossed: leave our children alone.”

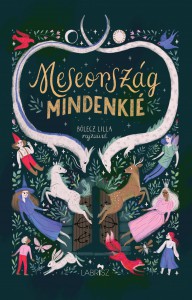

The book causing such an initial uproar, Meseország mindenkié (Wonderland Belongs to Everyone) is in fact a perfectly respectable collection of engaging stories, written by seventeen contemporary authors and beautifully illustrated by Lilla Bölecz. It contains allegorical stories, animal fables, and stories known from mythology or international children’s tales, retold in contemporary situations. What makes these texts stand out is that their protagonists aren’t the traditional heroes and heroines of fairy tales, but characters from diverse marginalised or minority groups. The narratives are told through the lenses of social and sexual identities, which focus on the issue of being different—a nearly absent consideration in mainstream Hungarian literature. The stories overtly address the difficulties of finding one’s way in the world and emphasize that whilst were are all one of a kind, we have a right to pursue our respective dreams. Each story foregrounds an important consciousness-raising issue and ultimately reaches the conclusion that all’s well that ends well, as long as matters are handled with willingness for acceptance and tolerance. The urgent need for inclusivity and equal opportunities underpins the collection. Among the protagonists is a young deer, who would like to grow antlers; a prince, uninterested in activities deemed suitable for him as a boy; an adopted boy, raised by an elderly couple after being abandoned by his birth mother; and a prince who only finds happiness once he meets a male partner.

In these stories, women are not portrayed as helpless creatures waiting to be rescued or offered as a reward to some male hero, but are strong, clever, and complex figures, capable of slaying giants if need be. Male characters are also given the opportunity to be more nuanced, not merely strong or powerful. Their interest lies not in their social status but in their personal qualities, which can include empathy or kindness.

As the volume editor Boldizsár Nagy notes in his foreword to the book, the collection was inspired by the idea of keeping the culture of fairy tales alive by repurposing and re-circulating the traditional stories. When commissioning the texts, the publisher (Labrisz Lesbian Association) asked contributors to retell a classical story from a poignant, personal point of view, offering space for contemporary experiences and drawing on protagonists whom minority and/or marginalised categories could identify with. Rather than privileging a didactic tone, these stories continue a counter-cultural tradition steeped in social critique and championing universal human rights. In this sense, the editorial intention has been to deliberately situate the volume in the tradition of eighteenth-century satire and seventeenth-century Italian storytelling, which explore individual freedom and a rejection of political and personal oppression. In this aspect, Wonderland Belongs to Everyone is an inspired volume of adaptations, where re-contextualisation and repurposing give relevance to the texts and attempt to challenge the current status quo. In other words, the myths and stories retold in the book adopt views that go beyond mainstream teachings and commonly held opinions. The origins of the stories remain recognisable, based as they are on well-known fairy tales such as Cinderella, Thumbelina, Snow White, and Hansel and Gretel, as well as Irish folk tales, Greek mythology, and a unique rewriting of Brecht’s Caucasian Chalk Circle. Yet characters such as an old Roma woman who saves the world, or people who want to change gender, offer an alternative reservoir of possibilities and of knowledge.

Another important facet of the anthology, conceived by project leader Dorottya Rédai, is that it offers a shared creative space for established and emerging voices, with some of the contributors having been selected after a nation-wide competition that attracted nearly a hundred submissions. Some of the well-known authors included in the book are Andrea Tompa, Petra Finy, and Orsolya Ruff. In addition, the project was carried out under the supervision of pedagogical expert Noémi Lőrincz with the collaboration of Emberi Jogi Nevelők Hálózata (Network of Human Rights Educators), an educational NGO that developed a series of activities for nurseries and primary schools to be conducted in parallel with the readings. These very detailed and carefully conceived activities (available on open access via the publisher and organisation’s websites), contextualise the stories and act as persuasive testimonies for a much-needed collaboration between state education and civil organisations.

As I write in early November 2020, this book is still the subject of intense scrutiny and is unavailable to purchase due to high demand. Until a reprint begins at the end of November, now may be a good time to reflect on such incidents, especially in the light of parallel protests against the government’s attack on landmark Hungarian cultural organisations. In recent years, the world-renowned Central European University was forced out of Hungary, countless media outlets were closed down overnight, and high-profile organisations such as the Hungary Academy of Sciences were obliged to restructure. The introduction of a new model of governance (essentially amounting to the loss of academic autonomy) at the University of Theatre and Film Arts (SZFE) in September 2020 has led to an unprecedented wave of dispute, lasting for months and involving ongoing strikes as well as the physical occupation of the university building by students. The latest in a long series, this protest against government-appointed academic leadership has far outgrown its origins in one organisation’s resistance to externally implanted management: it is now emblematic of widespread dissatisfaction with political control. This same control is indirectly linked to attempts at silencing a children’s book, even if, ironically, the book has now fulfilled its original remit, succeeded in busting taboos, and reached out to a potentially global readership, far beyond its initial target.

Meseország mindenkié © Labrisz Leszbikus Egyesület (Labris Lesbian Association), 2020.

The book can be pre-ordered via the following websites: lira.hu, Book24.hu, libri.hu, and bookline.hu.

Jozefina Komporaly is a lecturer in performance at the University of the Arts London and a translator from Hungarian and Romanian into English. She is editor and co-translator of the drama anthologies Matéi Visniec: How to Explain the History of Communism to Mental Patients and Other Plays (Seagull, 2015) and András Visky’s Barrack Dramaturgy: Memories of the Body (Intellect, 2017). She has published numerous works on theatre and adaptation, including the monographs Staging Motherhood (Palgrave, 2007) and Radical Revival as Adaptation (Palgrave, 2017). Her stage translations have been produced in London and Chicago. Her most recent translations, Mr K Released by Matéi Visniec (2020) and The Glance of the Medusa by László F. Földényi (2020) are published by Seagull Books.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: