It is impossible to think of Chinese modernist writing without the contributions of Eileen Chang, the Shanghai-born chronicler of twentieth-century social tumult, migrancy, urban dynamism, womanhood, and love. Across genres and languages, Chang’s work searches and breaches the intrinsic divides of society and culture to construct complex emotional architectures that are no less universal for their specificity, culminating in a body of work that coheres her various continents with perspicacity instead of generalization, centralizing the vital contemporaneous themes of fate, agency, and change. The collection Time Tunnel, a gathering of both stories and essays, illuminates the writer’s singular capacity to find the tenuous human threads that anchor down a restless era, evincing that nothing holds time together as much as living through it.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

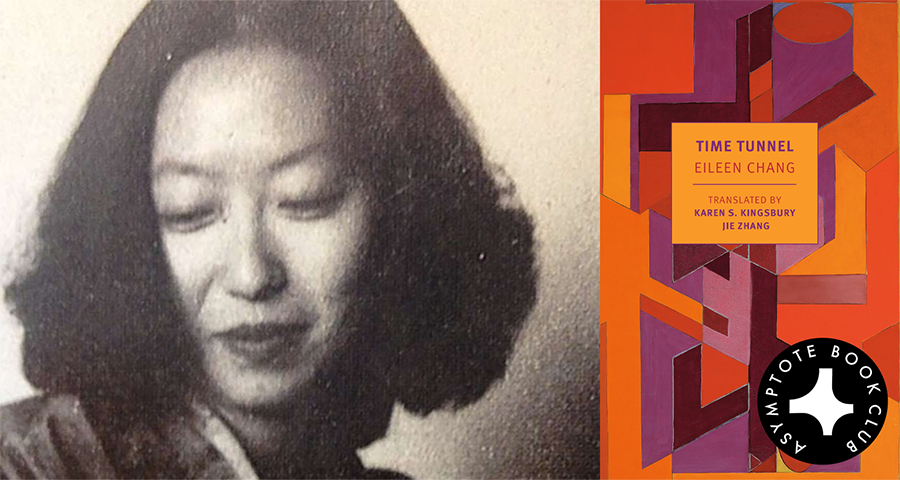

Time Tunnel by Eileen Chang, translated from the Chinese by Karen S. Kingsbury and Jie Zhang, New York Review Books, 2025

Eileen Chang’s lifelong literary project was, in essence, an extended act of self-translation and a continuous rewriting of identity—not only between languages, but across the seams of time and space. This ethos is threaded throughout the collection Time Tunnel, which takes its title and central metaphor from the story “Blossoms Afloat, Flowers Adrift” 浮花浪蕊:

… 时间旅行的圆筒形隧道,脚下滑溜溜的不好走,走着有些脚软。

. . . time travel’s round tunnel, slick underfoot and hard to walk on, feet went a little wobbly there.

The image gives shape to the collection and its stories and essays from across Chang’s career—including a hitherto unpublished manuscript from her husband’s papers, pieces translated from Chinese, as well as ones composed directly in English, mapping a landscape of displacement. As such, this tunnel is not a futuristic passage, but—as the translators Karen S. Kingsbury and Jie Zhang point out—“can only run backward,” pulling the characters and narrators into a precarious suspension between the author’s native Shanghai and an adopted America, between memory in the mother tongue and expression in another, between a haunted, bygone past and an un-belonging, unmoored present. This collection is a map of the footsteps left inside that tunnel: the subtle, often painful geographies of that in-between state. READ MORE…