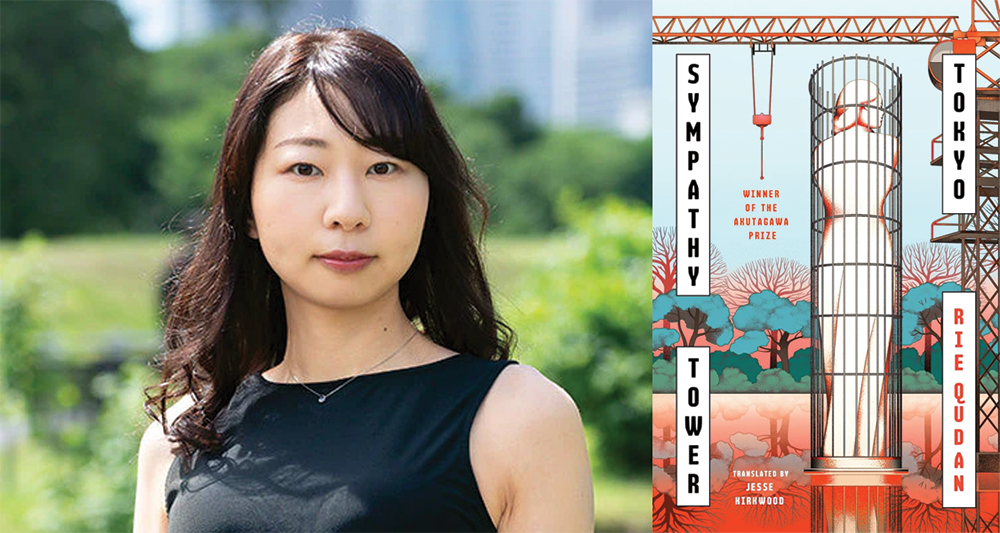

Sympathy Tower Tokyo by Rie Qudan, translated from the Japanese by Jesse Kirkwood, Penguin, 2025

Rie Qudan’s latest novel, Sympathy Tower Tokyo, garnered controversy in Japan when it won the prestigious Akutagawa Award in 2024. Questions immediately arose after the author announced that she used AI to help write parts of the story: around 5%, she specified. This led to the expected outrage regarding the dangers of AI in the arts, especially considering that the prize committee was unaware of its usage when they selected the novel. This is particularly interesting when at its center, Sympathy Tower Tokyo is a book about language—how words shape our thoughts and build our dreams—but it is also about the social consequences when language begins to lose its meaning.

Set in the near future, the novel’s igniting incident is a gigantic new prison being constructed in the heart of Tokyo. The commission for the building’s design has gone to celebrity architect Sara Machina, who wants to create a big beautiful tower, one that will stand in conversation with Zaha Hadid’s National Stadium. In this alternative Japan, Hadid’s stadium was built in time for the 2020 Olympics, which took place as originally scheduled (contrary to its delay due to COVID). The new prison, the titular “Sympathy Tower,” is intended to be a place of rehabilitation for those labeled Homo miserabilis, or “humans deserving sympathy.” It is thus meant to convey the idea that incarcerated prisoners are themselves victims of systemic economic and social injustice—including murderers and rapists. READ MORE…