In Carolyn Forché’s poem, “What Comes,” she writes: “To speak is not yet to have spoken.” Amidst the myriad of voices clamouring to be heard today, writers often aim to reconcile the journalistic motives of witness and the cultivated balance of narration, bringing the scattered language of a society into a solid, comprehensible whole. The best of these texts has proven to be a powerful tool in re-establishing the broken links between people living under a regime, and in a newly released book from Thailand, an anonymous writer seeks to do the same in a fascinating and deeply probing exploration of the country’s strictly enforced lèse majesté laws.

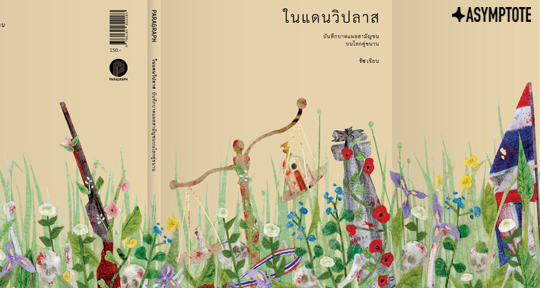

What can literature do during times of emergency, wherein testimony takes precedence over much of storytelling? This year in Thailand, amidst the ongoing crackdown on anti-government protesters—exacerbated by viral outbreaks in prisons—witness accounts by lawyers and journalists have assumed the task usually assigned to literature: to describe the human condition and to build conscience. One particular book, however, has managed to straddle the worlds of journalism and literature. A collection of anecdotes about those affected by the lèse majesté law in the 2010s, ในแดนวิปลาส (In the Land of Madness, Paragraph Publishing, April 2021), has much to teach us about how to tell the stories silenced in the throes of oppression and censorship. It is anonymized yet revealing, packed full of pain but with surprising touches of humor. Perhaps due to its relevance to current events in the country, the book has seldom been considered as a literary object. Yet, in its description, the book categorizes itself as a “Thai novel.” This gets my puzzle-solving mind turning.

One might read the categorization as ironic, and—taking “novel” to mean fiction—come to the truism that, in the Kingdom of Thailand, the truth surrounding the monarchy and its victims must, for reasons of safety, make itself anonymous, dressed up as fiction. But reading the label as a genuine attempt to define itself may yield deeper and more surprising insights. In the author’s preface, a line is drawn between reporting based on facts and storytelling based on feelings:

All the stories in this book grew out of prying curiosity indeed. Half of its fruits became serious news and information while I worked as a journalist in a small but big-hearted news agency; the other half turned mostly into emotions and feelings I put away in a bag and didn’t know what to do with.

In a situation where rights and liberties were repressed for a long time, where injustice was standard practice, the bits and pieces being collected in my bag kept getting heavier and heavier, to the point where the bag seemed to be bursting. There were two parallel worlds. People lived normal and bright lives in one, while the other was pitch dark, cruel, and noticed by very few. One stranded between the two worlds would therefore find it extremely difficult to maintain one’s sanity and normalcy.

It isn’t that fact and feeling are necessarily opposed; rather, the preface suggests that there is a remainder left over from the work of journalism—that certain parts of a journalist’s experience can only be stored as feeling and emotion. Shining the “spotlight” on society’s darkest corners provides only one aspect of reality. The other sides—unspoken or unspeakable, unborn or unbearable—are best accessed via novelistic means. In the Land of Madness definitely ‘reads like a novel’ in the sense that it is a well-crafted, compelling story wherein some characters are depicted with vivid inner lives, whereas others remain unknowable despite their palpable presence on the page. Calling it a novel also allows for some artistic license, a deviation from factual description to get at a deeper truth; in the book’s most surreal moment, the narrator notices a friend’s “internal” injuries by seeing lances of sunlight piercing through holes in his frame. READ MORE…

From Silly to Deadly: On Shalash the Iraqi by Shalash

. . .key to the humourist’s arsenal is none other than language itself—its malleability, its capacity for aggrandisement and diminishment alike.

Shalash the Iraqi by Shalash, translated from the Arabic by Luke Leafgren, And Other Stories, 2023

Anonymity fascinates and seduces. Endless speculations have circled invasively around who Elena Ferrante “truly” is; Catherine Lacey’s recent Biography of X reckons with erasing a layered past with a single letter of the alphabet; the first season of Bridgerton, the hit Regency-era romance on Netflix, has its narrative engine propelled by the question of Lady Whistledown’s real identity. These instances from the Global North exemplify the allure of mystery, but they fail to account for the stakes of remaining nameless in a political climate where to unveil oneself might be to threaten one’s own safety.

One might, in a moment of facetiousness, think of the eponymous chronicler of Shalash the Iraqi as the Lady Whistledown of Iraq’s Sadr City (or Thawra City, as it is lovingly christened by Shalash). Both issued frequent dispatches from within the epicentre of social disarray, guaranteeing the pleasure of gossip. More importantly, their pseudonymous veneers facilitated a lurid candour that might not otherwise have been possible.

There the similarities end. The respectable circles of upper-crust London did not live in the penumbra of foreign occupation. Nor were they plagued with the constant risk of spectacular sectarian violence, or hampered by a corrupt government that has “thieves, cheats, swindlers, traders in conspiracies” for politicians. It was against such chaos that Shalash released his explosive, timely blog posts, garnering a rapidly expanding local readership despite patchy Internet access in the country. The academic Kanan Makiya tells us, in his introduction, that people were printing out the posts, “copying them longhand,” “bombarding Shalash with questions and opinions.” Even high-ranking cadres could not resist partaking in the fanfare: one official expressed admiration while entreating Shalash not to mock him, for fear of his children’s potential disappointment. Another claimed that upon reading the daily communiqués, he would fall off his chair laughing.

Laughter, perhaps, can always be counted on to forge an affinity, if not a unity, beyond fractures of sect, status, and ethnic affiliation. Iraqis would “drop everything for a good laugh”; they gather in bars and down glasses of arak to immerse themselves in a “great, communal, and nondenominational drunkenness.” Shalash knows this, and abundantly turns it to his advantage. Nothing and no one is spared from the crosshairs of his ridicule, populated by a variegated cast that encompasses sermonisers, soldiers, suicide bombers, and donkeys. A vice-president’s verbal pomposity sounds like “he just ate a few expensive dictionaries and is about to lose his lunch.” A woman about to be married off to an Australian cousin is told, should her fiancé divorce her, “just tell everyone that he’s a terrorist and you’ll have nothing to worry about.” An odious neighbour, eager to save a spot for himself in paradise, proselytises the necessity of voting in the referendum for Iraq’s new constitution: “Don’t you know the going rate for rewards in heaven for helping ratify the constitution? It’s worth a hundred visits to the shrine of the Eighth Imam, and that’s on the far side of Iran!” When the narrator casually uses Google Earth, he is accused of lecherously spying on the women of his residence, sparking off a widespread hysteria—and court case—about the “violation of the morals of the block.” Each instance of mockery is a shard in a wider mirror of collective trauma.

READ MORE…

Contributor:- Alex Tan

; Language: - Arabic

; Place: - Iraq

; Writers: - Abu al-Qasim

, - Ahmed Saadawi

, - Catherine Lacey

, - Elena Ferrante

, - Emily Dickinson

, - Hassan Blasim

, - Kanan Makiya

, - Maya Abu al-Hayyat

, - Shalash

; Tags: - American occupation

, - anonymity

, - arabic literature

, - blogging

, - humor

, - Iraqi literature

, - social commentary

, - US Invasion of Iraq