This article by the prodigious French writer Marie Darrieussecq appeared in Le Monde des Livres on May 11, 2017. The occasion was the publication of the two-volume La Pléiade edition of the Complete Works of Georges Perec, who died thirty-five years ago, in 1982. It is a huge honor for a writer’s work to be published (usually posthumously) in the Bibliothèque de la Pléiade, which is a critical edition, with annotations, notes, manuscript and editorial variations, and accompanying documents. The books are pocket format, leather bound, with gold lettering on the spine and printed on bible paper. The series was begun in 1931 by the editor Jacques Schiffrin and was brought into the Gallimard publishing company in 1936 by André Gide.

—Penny Hueston

Georges Perec is now part of the Pléiade series. The novelty of the list of his titles being collected in this edition might have brought a smile to his face. He used to say, “Nothing in the world is unique enough not to be able to be part of a list.”

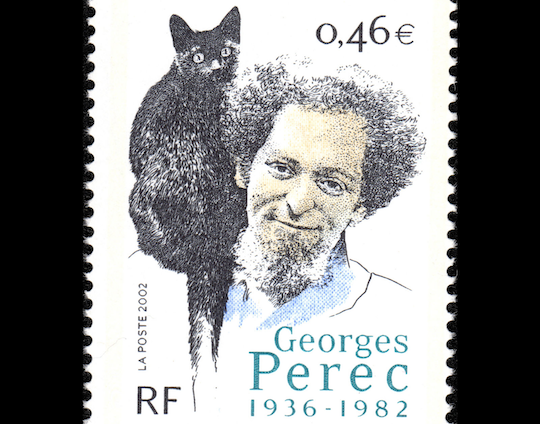

But Perec is unique. More than anyone else’s, his collected works resemble a UFO. He is a successor to Jules Verne and Herman Melville, to Stendhal and Queneau, to Poe and Borges, to Rabelais and Mallarmé…And yet Perec stands alone, bearded, playful, coiffed with a cat in his hair, like an icon in our popular imagination. And, although a dizzying number of references are woven through his work, his way of writing is freakily inventive.

His books were only intermittently successful in his lifetime, but after his premature death at the age of forty-six in 1982, his reputation grew exponentially. Perec quickly became the most recent of our classics. “A contemporary classic,” as the editor of this Pléiade edition of his Complete Works, Christelle Reggiani, writes in her preface, but an odd classic, both amusing and melancholic, whose humour shaped his despair.

His lipograms, constrained writing (the speciality of Oulipo, of which he was without doubt the most famous member), play around an absent centre, a missing letter, or an alphabetical prison house. His novel, A Void (1969), written without the letter “e,” is therefore written without them: without his father, who was killed in the war, without his mother, who was murdered in Auschwitz.

What seems to be Perec’s pleasant game with words is his way of saying the unsayable, of giving shape to absence, of proclaiming the abomination of the death of his mother and of the destruction of the Jews of Europe. He had what it takes to write that. READ MORE…