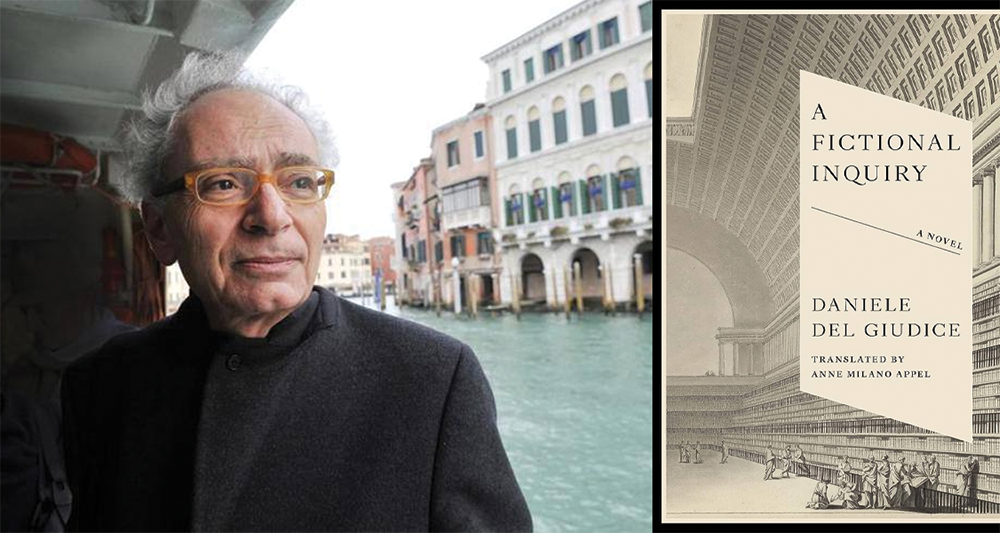

A Fictional Inquiry by Daniele Del Giudice, translated from the Italian by Anne Milano Appel, New Vessel Press, 2025

A Fictional Inquiry, Daniele Del Giudice’s first novel, is called Lo Stadio di Wimbledon (Wimbledon Stadium) in its original Italian—a reference to the end, when the protagonist journeys to Wimbledon to finish his, as translator Anne Milano Appel puts it, “inquiry.” The English title is clever; it places the conundrum of Del Giudice’s story right on the cover.

The titular inquiry is regarding the Triestean writer Roberto Bazlen, whose novels were published posthumously. The unnamed protagonist of A Fictional Inquiry travels first to Trieste and then to London, trying to understand why Bazlen did not or could not write while he was alive: “‘How did he hit upon the fact of not writing?’ I ask. ‘I mean the fact that he only wrote in private?’” Obviously, this inquiry concerns a writer of fiction, but it is not solely a question about what it means to write fiction; in a double meaning, the man’s inquiry is itself fictional, tossed out to the reader to cover up the protagonist’s (or Del Giudice’s) other, hidden, purpose.

This character arrives in Trieste with the supposed goal of interviewing Bazlen’s surviving friends and colleagues. He claims, during these encounters, to be gathering information in order to figure out why Bazlen never revealed himself as a writer, and as a result, these conversations map out his subject’s literary life. For some reason, however, the man is continually uninterested in the conversations he’s having. While speaking to a poet in her hospital room, he thinks: “I don’t care to listen to anymore; I want to leave, but I’m anxious about the formalities.” Before and during other meetings, he is just as hesitant. When asked if he is available to see a person of interest on that day, he responds: “Yes of course,” even while admitting to us that: “Truthfully I don’t know if I want to.”

His mindset does not seem to correspond to that of someone who would travel such distances and go to such trouble to look up and visit Bazlen’s surviving friends. The visits themselves are also notably not interviews; the protagonist barely asks questions, instead allowing his conversant to ramble. Then, having received all that information, he reacts: “It’s hard to know what to do with all this.” It’s not that the protagonist is totally uninterested in Bazlen—something more extreme is at work; he tries to avoid Bazlen’s name in conversation, and deliberately crosses his eyes to avoid looking at photographs of the writer. So what is he trying to do on this journey? This man has gone to the effort of visiting Trieste and London, and he still continually attempts to convince both the reader and Bazlen’s friends that he genuinely cares about the answer to his chosen inquiry.

To understand Del Giudice’s protagonist, it is necessary to look at his first meeting with one of Bazlen’s friends, a poet at the hospital:

She makes a more inclusive gesture. “Maybe this doesn’t interest you. What is it that you want to know about him?”

“Why he didn’t write.”

I chose the most salient issue, in any case. She opens her mouth, not saying anything.

This moment is the first time the protagonist has vocalized his “inquiry,” but he has also couched it in some interesting language. Appel has the protagonist use the word “salient” in English, which seems to imply that the issue of Bazlen’s writing is the most conspicuous or perhaps the most topical issue—but not necessarily that it is the most important issue to him. “Most salient” implies a multiplicity as well, but the novel that follows has the protagonist exclusively refer to this one issue; in future conversations, he never again references his other “issues.”

After each subsequent conversation, the protagonist adjusts and adds the information learned during that conversation to his own character. When he meets with the poet, he says aloud that he wishes to know about Bazlen’s writing; this topic then becomes the core of every future conversation. Next, he sees another of Bazlen’s friends at a cafe, and this meeting prompts the protagonist to say of the writer:

Nonetheless, he wrote, in an underground, parallel way, just enough to make it clear that he would not write. That’s why he’s there, in that center zone. I’ve also read that that center doesn’t exist, it’s a void.

After exiting the cafe, the protagonist uses this concept of the void to make an observation, one that he continues to refer to across the remainder of A Fictional Inquiry: “I’ve started dividing the city that way: everything to the right of the station is ‘toward Yugoslavia,’ everything to the left is ‘toward Italy.’ Here we are on the right.” The station, in the protagonist’s map of the city, is the void, is Bazlen—and the station continues to be the void as the protagonist applies this map, thinking: “we are going to that part of the city that I think of as ‘toward Yugoslavia.’” The manufactured association between Bazlen and traveling becomes more precise; a later conversant has sextants hanging in her house, which become another consistent topic of focus for the protagonist. The idea of navigation and the distance between objects somehow becomes linked to Bazlen.

The protagonist explores Bazlen in these roundabout ways, taking a specific view or aspect of his subject from each conversation, temporarily detaching it from Bazlen, and then adopting it into his own character. In this way, the protagonist slowly becomes the author as he makes his final journey to London. He uses things newly associated with Bazlen as he spans the distance between two cities; he travels, an act motivated by Bazlen. In Wimbledon, he has his final conversation with Ljuba Blumenthal, Bazlen’s long-time lover, and at the end of the conversation, she gives him a grey sweater—Bazlen’s sweater—asking him to put it on. After this final conversation, the protagonist leaves with an object attached to him, and unlike the ideas and frameworks he adopted after each prior conversation, the sweater disturbs him:

Occasionally on the way down I think about the thickness of my shirt. I also ponder whether there may be a relation between the duration of exposure to the pullover and any possible effect. I walk with a stiff, hurried pace, as if enclosed in a suit of armor. I wonder how many words it would take to explain the situation to the people sitting quietly in those gardens in front of their homes in the late afternoon.

The little station’s chimney pots come into view; I go up the steps, buy a ticket to Heathrow from the ticket agent. I continue walking down the empty platform to a little building at the end, marked Gentlemen, which practically overlooks the fields. In there, amid a rush of running water, I search for a hook on the red-and-white painted walls and finally hang my jacket on the edge of a door. I slip off the sweater, lay it on my bag. I put my jacket back on and run a hand through my hair to straighten it, though there’s no mirror. From outside there is a resounding screech.

In this, it is revealed that two Bazlens appear to the protagonist: the owner of the sweater who existed in the real world (or perhaps, it can be said, the sweater itself), and the Bazlen who represents literature, navigation, mapping spaces. The protagonist, by removing the sweater, is rejecting the Bazlen of the real world, but even as he does so, he doesn’t choose the Bazlen of the literary world—because much more than the act of traveling, the protagonist is obsessed with the objects that allow one to travel: trains, buses, ships, and planes. Del Giudice spends pages upon pages detailing their inner workings, compelling a meditation on what it means to move in a space that one is also simultaneously creating. Within a train, the protagonist observes a child:

First of all, the child moving his little plastic train up and down against the window glass, maybe thereby experiencing the childish completeness of being inside something while still being in possession of it from the outside. He’s quite focused as he plays, but the toy train may compensate for the loss of an external form that is no longer visible. He plays with it spontaneously, in the most perfect way, as is the case with a toy train in a train.

“Being inside something while still being in possession of it from the outside” is described as something “perfect” to the protagonist, who decides, having created Bazlen’s world within his own and then rejected it, that the most “perfect” thing to do is to map the world then play with that map: that is, to write. In this, A Fictional Inquiry itself accords with the protagonist’s theory of literature; although the novel is written entirely in first person, Del Giudice obscures the protagonist’s real wants and motivations, creating a character who seems to drift around in the novel, who is artificially pushed from conversation to conversation, from city to city. As the boy plays around with the toy train, Del Giudice recreates an existing landscape in miniature, to play around with his protagonist.

A Fictional Inquiry ends with the protagonist taking off that sweater and choosing to write—perhaps a representation of Del Giudice himself with this first novel, this decision to write publicly. A Fictional Inquiry is not a justification of that choice, but perhaps a mapping of the processes experienced by Del Giudice before arriving at the conclusion to live more perfectly inside a novel—which is a mapping of the real world—rather than to live only within the real world, like Bazlen had. The resulting fictional narratology, carefully brought to life in English by Appel, forms a fascinating early work about a man’s unwavering decision to choose literature over a literary life—over a life full stop.

Ria Dhull is an artist and collector based in New York City. She reviews film for Spectrum Culture.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: