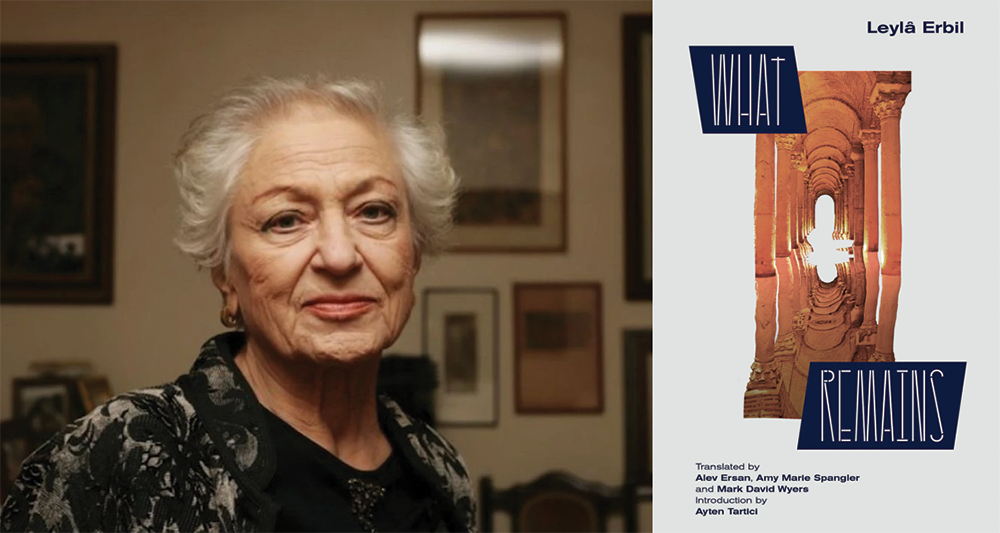

What Remains by Leylâ Erbil, translated by Alev Ersan, Mark David Wyers, and Amy Marie Spangler, Deep Vellum, 2025

In 2022, the publication of A Strange Woman (Tuhaf Bir Kadın) introduced the renowned Turkish writer and activist Leylâ Erbil to the Anglophone literary world, a step made possible by the efforts of translators Nermin Menemencioğlu and Amy Marie Spangler. What Remains (Kalan) now gives us a new side of Erbil—her first novel, characteristic with her uncompromising commitment to exploring the taboo. In a delightful moment of parallelism, Maureen Freeley’s translation of Journey to the Edge of Life by Tezer Özlü, one of Erbil’s most beloved friends and regular correspondents, came out in April, making 2025 a watershed year for Turkish women writers in translation.

Ayten Tartıcı’s insightful introduction to What Remains sets the stage beautifully, giving the reader enough context to get a sense of Erbil and her work while preserving room for mystery and surprise. Born in 1931, Erbil grew up in Istanbul and was an autodidact who did not believe in shutting herself inside the ivory tower of academia. She read widely, immersed in the work of her Turkish contemporaries but also global thinkers and writers like Kafka, Proust, Freud, Faulkner, and Marx. Undeniably a brilliant and prolific writer (as the first Turkish woman to be nominated for the Nobel Prize in Literature), she was passionate, opinionated, and politically engaged in both her texts and her life, advocating for freedom of expression in Turkey and beyond.

Erbil was not afraid to take risks with form and subject matter. In an interview from 1997 published in Zihin Kuşları (Birds of the Mind), an untranslated collection of her non-fiction, she observes that “in this country, truthfully expressing your thoughts, revealing facts, or ‘being for oneself,’ are equivalent to risking your life.” A Strange Woman received critical backlash for its candid explorations of sexuality, mental illness, abuse, and even incest. She was not afraid to take her writing to places that would make people feel uncomfortable or offended. In this, Tartıcı rightfully stresses Erbil’s uniqueness in the global scope of literature, “as she forges a new and self-aware diction to give voice to women who seek their own pleasure, who read, argue, and think in a society that all too often glorifies female chastity and subservience as virtues.”

Published in 2011, just two years before her death, What Remains showcases Erbil’s daring and her disregard of approval within conventional literary and intellectual spheres. There is a notice that comes before the dedication that reads, “This book has never been submitted for any ‘awards.’” Erbil was candid about her apathy for prizes, which she felt mistook subjective taste for objective quality and value. Notably, the original Turkish title of What Remains, Kalan, is singular but functions as a kind of collective noun, meaning something like remainder/the rest/residual. “What Remains” elegantly captures the plurality that lurks behind apparent singularity, a metaphor for the city of Istanbul itself but also the book’s translation process. This book is the collaborative effort of three translators, Alev Ersan, Mark David Wyers, and Amy Marie Spangler, whose distinct voices and approaches are synthesized in the finished product: a novel that stretches the boundaries of the narrative form, composed as a stream-of-consciousness lyrical prose poem divided into two chapters.

The book starts with a “proem,” harkening back to the tradition of ancient epic. It is written entirely in lower case letters, and the only consistent punctuation is a series of three commas in a row, functioning as a kind of breath for the reader. The narrator, Lahzen, often addresses her readers as “you,” creating a sense of intimacy, but switching occasionally to a self-referential “you” in italicized passages that seem to capture her internal monologues. The effect is akin to a series of impressionist paintings rather than a piece of narrative art. In the aforementioned 1997 interview, Erbil articulates her grammatical interventions as arising from her view of humanity, which seems Nietzschean in spirit: “we are all crippled, injured . . . therefore describing [people] with conventional phrases or having them speak in the first person may not be sufficient. The sentence structure, the play on words, the transformative discourse forces a change in classical conventions.”

At the heart of the book is a dirge for what has been lost in the formation of the Turkish state and its accompanying nationalism. Erbil grew up in a multicultural and multi-faith Istanbul, with a palimpsestic chorus of hybrid languages and traditions. When reflecting on her childhood, Lahzen describes a familiar Greek song in their neighbourhood as “a resilient spider web [that] resounds through streets and houses.” Greek businesses stood happily alongside Turkish ones in a cosmopolitan melting pot, and even Lahzen’s very home signifies this fusion: “there stands our three-story timber house / the work of a greek craftsman named hadji murat.”

Permeating the novel is the weight of Turkey’s violent past and the glorification of such violence, a lineage that stretches back to its Ottoman history. The translators added an expansive glossary to supplement Erbil’s own list of characters to help readers navigate the numerous references and names. Lahzen reflects on learning, for example, about Suleiman the Magnificent’s massacre of Hungarian forces at Mohács in the sixteenth century: “our elders expected this of us, expected us as youngsters / to be in awe of our past / even if this rusted-out demand / weighed heavily upon us.” What Remains is thus set in the shadow of state sanctioned violence, making reference to the assassinations of Kurdish journalists, politicians, and revolutionaries; the murder of anti-fascist students; and, most robustly, the Istanbul pogrom of September 6-7, 1955, a largescale attack on the Greek population, as well as Greek homes and businesses. This persecution caused a swift and profound emigration of Christian Greeks from the city.

In the wake of such loss, Erbil explores the absent presence that haunts Istanbul, much as Eliot does for postwar London: “beneath the remains . . . leading down into endless layers of the past / this merciless city / assailed by our civilization, / considered both foreign and ours / both ours and not / bearing the soul of both above and below.” The foreignization of non-Turkish people in Istanbul—a famous meeting point between west and east—in turn destabilizes the identities of those left behind: to whom does the city belong, and how does one feel at home amidst the void left behind by those who were forced to leave, whose ways of life became embedded in the very material of the land and cityscapes? Lahzen is fittingly obsessed with architecture and archaeology—in particular stones, which she sees as unbroken ties between the past and the present. The men in her life insistently dismiss this romanticization; when she asks a lover, “couldn’t it be that the cells of stones have merged with my own,” thinking about the commingling of matter over time, he accuses her of madness for self-identifying with an inanimate object. When she visits Mount Nemrut and brushes her cheek against one of the giant stone statues, her husband at the time replies, “what a disgrace, embarrassing yourself like that in front of these foreigners!” Yet Lahzen feels a connection with these markers of time that transcend religious or nationalistic boundaries.

Erbil once remarked, “This madness and wretchedness that I see inside every human being is the source of my art.” Madness is certainly the affective mood of the novel, and it picks up on the psychologically fraught landscape of A Strange Woman. Lahzen muses, “after witnessing this parade of demons all my life / how is it i ask you / that i’ve not lost my mind / or have i . . . am i the only one in this country who’s gone mad / what about you.” A profound splitting of the self takes place in the wake of persistent brutality: “every day i ask myself where within my lived experience am i living / lahzen in which consciousness are you.” The emphasis on asking in both passages indicates the book’s atmosphere of uncertainty, which extends to the authorship of the text; in a moment of striking autofictional collapse, Lahzen says she will write a book called A Strange Man, the actual title of one of Erbil’s other books, and she references “a short story by leylâ erbil.” The author herself becomes embedded in the fictional world of her story.

Madness tends to be inflected through a gendered lens in Erbil’s novels; not only do women grapple with the same socio-political vicissitudes as men, but they are subjected to patriarchal forms of oppression, control, and surveillance. It therefore becomes imperative to “protect yourselves from men” given their inclination to anger and violence. Women’s bodies are not just at stake, but their minds as well. As Lahzen keeps getting distracted while trying to narrate a story from her past, she remarks, “you can see i have a brain that i can’t rein in / it’s a bit on purpose perhaps but to stop this brain / my doctor wants to drown every last cell of it in pills but still I / will try to leave the writing of this text / to a troubled brain that knows no bounds.” Her creative freedom rests on the uncontainedness of her psyche and her refusal to submit to a numbing prescription of normalcy.

As such, fissures as both dividers and gateways, material and psychological, appear in numerous guises throughout the novel. Lahzen reminisces on her treatment of her uncle’s backyard mosaics: “sometimes when I was little if there was no one around / i’d pick up a stone and use it to smash another to pieces / but then when one is little / one thinks that everything contains something else.” The persistence of weeds sprouting up among the interlocked tesserae, regardless of her secret vandalism, demonstrates to her that “a crack can form between two things at any moment / a void no matter how much you long to bring them together.” Erbil is a chronicler of the cracks, of what disrupts a sense of wholeness and cohesion but also evades hegemonic structures of conformity.

One of the novel’s most formative scenes features another kind of breaking: “that accursed day when i left my pencil case at home / that day when rosa ‘crack’ / broke her pencil in two handing me one half / saying, here, / carving that sound into my own personal history / laying the groundwork for who i am today.” Rosa, Lahzen’s childhood best friend, “whose face was one of giggling freckles,” is an essential figure in the text: “it was with her I shared my everything.” The “crack” incited by Rosa’s sharing of her pencil opens up the space for their relationship to flourish. Rather than losing herself in a void, Lahzen comes to find herself: it is an act of breaking apart inspired not by violence, but by generosity, that enables one of the most important unions of her life.

Throughout What Remains, Lahzen grapples, often quite amusingly, with the thought of Kierkegaard, whom she calls by his first name, “søren,” and labels “a nutcase.” He proves to be her intellectual nemesis and the medium through which she wrestles with questions of faith, meaning, and truth. At the end of the book, she resolves, “i’m not going to read any more philosophy, i’m going to recreate the world from scratch all on my own.” Reuniting with Rosa after a long separation, Lahzen tells her that they will await the arrival of the revolution together, and her friend insists, “we better get to work.” Lahzen’s renunciation of pure abstraction in favour of transformative and transgressive creativity, coupled with Rosa’s insistence that they not just think but act, is perhaps a call to fiction as the answer to the restlessness and fragmentation of modern Turkish existence.

Lahzen is constantly excavating older iterations of landmarks and places or ones that have been forgotten, a process or reclamation that is akin to her splitting open stones to see what else might be contained within the outer shell. In one stream of consciousness vignette, she proposes that the mythical Burnt Gate of Istanbul rather than the famous Theodosian Golden Gate might be

the more appropriate passage to the virtuous chamber of my truth . . . though when i say ‘burnt gate’ don’t imagine / a gate of burnt wood / sure it may show signs of wear and tear here and there just like me / yet there remains an opening between the columns the blocks of stone / a narrow passage . . . so that you may pass through.

I can’t think of a more fitting image for the psychological world of Erbil’s writing—full of scars and wounds, marked by its past, feeling a heaviness akin to stone, but nevertheless opening up a gap, a source of hope that there is a way through what seems impenetrable—that “what remains” can be more than a site of irreparable loss; it can be a foundation for a different future.

Hilary Ilkay works in sales for the Canadian indie press Biblioasis, and she is an Associate Fellow in the Early Modern Studies Program at the University of King’s College in Nova Scotia. She is a Managing Editor for Simone de Beauvoir Studies Journal and an Assistant Managing Editor for Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog:

- Life Adorned with a Little Death: A Review of Journey to the Edge of Life by Tezer Özlü

- A Perpetual Coming-of-Age: On Cold Nights of Childhood by Tezer Özlü

- Strange and Stranger: On Leylâ Erbil’s A Strange Woman