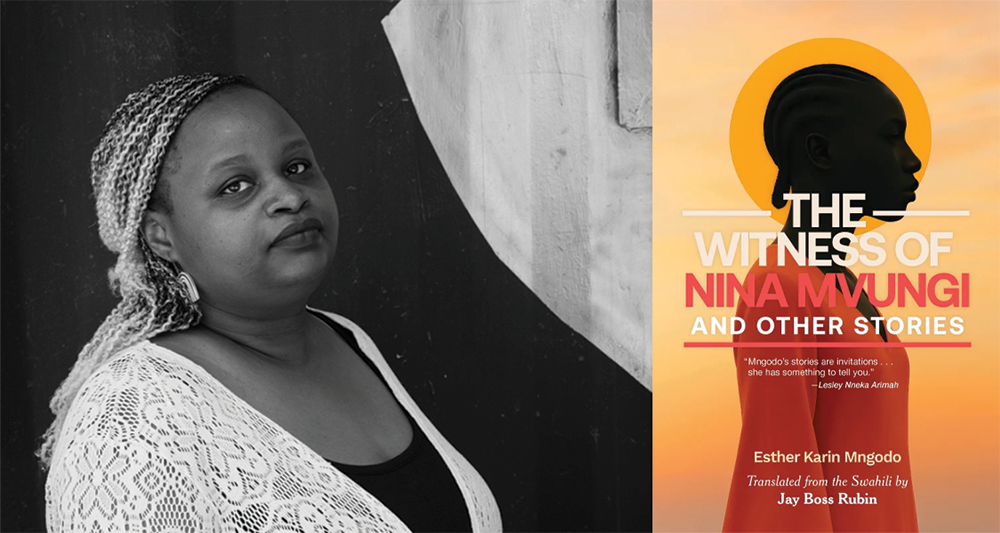

The Witness of Nina Mvungi and Other Stories by Esther Karin Mngodo, translated from the Swahili by Jay Boss Rubin, Hanging Loose Press, 2025

Each story in Esther Karin Mngodo‘s short story collection, The Witness of Nina Mvungi and Other Stories, work together to compose an intricate web, with ongoing threads of entrancement cocooning readers from beginning to end. Beautifully translated from Swahili by Jay Boss Rubin, the prose grips and refuses to let go, revealing the rawest truths of the human condition.

The collection is a mixture of realism, Afrofuturism, and speculative fiction. In one of the stories, a woman and man are on a date at the theater, and one quickly realizes, in a meta turn, that the play they are watching is actually an apocalyptic story from earlier in the collection. In the middle of the play, a scream emblematizes the center of the interconnected narrative and terrifies the protagonist in the story: “I nearly went into shock. My whole body snapped to attention. I wrapped my arms around myself so I wouldn’t have to run away or hide under my seat.” Contained in this bloodcurdling scream are all the themes explored in The Witness of Nina Mvungi and Other Stories: betrayal, jealousy, negligence, violence, powerlessness, loss—feelings that so many of us suffer through alone and in silence.

Yet suffering is not limited to what the characters in the book go through. By tactfully using the second person in the introductory story, Mngodo immediately blurs the line between reader and character; “You” enter the story as Sofia, a wealthy thirty-year-old woman who works as “the Director of an NGO that raises awareness about issues affecting girls in education.” You’ve decided not to walk the traditional path of finding a husband and having children, but to focus on your career—and you are happy with this decision, with your “coffee-colored lens” sunglasses, your stainless white blouse, the Land Cruiser your driver Ibrahimu drives you around in. That is, until you are suddenly confronted by an unfamiliar man whose body “looks wasted away, and his clothes unwashed for who knows how many days . . . You see dark splotches on his skin . . . brown stains cover his teeth.” You think, “He might have a knife, razor, metal bar, or something else he could hurt you with.” Thankfully, he doesn’t have those things and doesn’t hurt you—he simply asks to use your phone to make a call to the mother of his daughter in England. However, the calls fail, and the man is left powerless and alone. You leave him there, without even a goodbye, not only because you fear backlash, but because his sorrows are a mirror reflection of your own. “I can’t call our child on the phone. I can’t, Ibra,” you say, while he drives. You yourself have lost a child, and with this experience, the pain comes flooding back. “Tears flow out of you. You don’t restrain them any longer.” This final line is perhaps an invitation for readers to also let the tears flow—the story a safe space to be free from restraint, even for a little while.

In the penultimate story, “Aisukurimu,” the perspective shifts to that of a little girl’s. She is sitting in her uncle’s car eating ice cream, and what starts out as a nostalgic moment turns sour very quickly. The seemingly small details in the short story reveal the neglectful situation the little girl is in; her mother calls, and when she picks up excitedly, her mother says without so much as a greeting, “Put your uncle on.” Her heart is shattered, and in an attempt to console herself, she asks her uncle to help her take the wrapper off the ice cream even though he is driving and talking on the phone. “It was fine, so long as he was struggling for me,” she says. Her deep-seated loneliness is made increasingly visible up to the very last line: “I never knew that you could be happy and devastated all the same time. I never knew.”

This line leads readers to the final story in the book, “Rare Goods,” which is also told from a child’s point of view—but this time, a young boy with albinism. This realistic fiction piece addresses an ongoing issue that the albino community in Tanzania face: witch doctors who prize their body parts and try to steal them. In the story, albino children from the village band together to form The Secret Albino Society to protect themselves, coming up with ways to fight Tuf Tuf, a man with a rifle known to steal albino body parts. Readers desperately want the Secret Albino Society to persevere, but a sickening betrayal at the end of the story leaves us closing the book with anger and sorrow, the situation having been portrayed not with false optimism but a devotion to its severe reality. Across the collection, these stories are unforgiving and gut-wrenching, a reminder that reality is often the same.

I sympathized with many of the characters and their extremely difficult fates—usually a consequence of patriarchy and its detrimental effects. And while one can certainly interpret Mngodo’s work as a sharp, honest commentary on the inequal world we live in, she is also pointing out a much softer and personal reality with these stories: that what connects each of us is the simple desire to be witnessed.

This is perhaps most evident in the titular story, “The Witness of Nina Mvungi,” in which an invisible, alien character named Brother Morpheme is on the verge of being fired from his position as a Witness for earthly humans. The rules for the job are: 1) get to work on time; 2) remember everything that happens to each of your subjects; and 3) to not get emotionally invested. Despite having witnessed the lives of 150,982 humans so far, he feels a deep attachment—even a love—for his latest subject, Nina, and becomes desperate to make his presence known to her.

What follows is Morpheme the Witness’s uncontrollable desire to be witnessed himself. “I need her to see me, finally,” he says, as he watches Nina struggle. Having lived through countless painful experiences, she cries most nights, and on one such evening, she says, “I wish someone was here to see this. Not just the shitty things, but all of it. I wish someone knew me inside out. Why do I feel so alone? I want love.” When hearing this, Morpheme’s desire to appear peaks—but of course, this is against cosmic protocol. When he confides in his colleagues, they attack him with criticisms, insults, and warnings.

Both Nina and Morpheme want to be seen, yet they cannot do that for one another because mutuality is not something a Witness should partake in. As one begins to question why a connection can’t be made between the two—especially because Morpheme has also watched Nina’s ancestors and knows everything that’s happened in her life. It’s very likely that some of her sadness and loneliness could be alleviated if she discovered that she has had a Witness the whole time, but rules and the status quo work to keep the two apart. Eventually, the two do get to meet, but when Nina sees Morpheme, she is terrified. Morpheme revealed himself without thinking about how she might react.

As a translator myself, I couldn’t help but compare this painful dynamic between Morpheme and Nina to that of a translator and author. It is often said that the “best” translation is one that reads like an original; we are meant to disappear, to become ghosts. Like a Witness, translators work behind a curtain, expected to adhere to the strict rule of not “interfering” with the original. But what is the benefit of a translator’s disappearance? Could the translator stand alongside the author?

The Witness of Nina Mvungi and Other Stories seems to state that they can. Mngodo and Rubin worked collaboratively on the stories in this collection, and as the latter describes in his introduction: “. . . our conversations began as suggestions for individual line edits. But our explanations and elaborations grew and grew, and the word counts in the margins soon outpaced the word counts in the stories themselves.” Unlike Morpheme and his rashness, Rubin was careful in his methods, and the collaboration happened over the course of lengthy conversations and careful exchange. With this process, not only do Mngodo and Rubin push back on the idea that a translator could somehow “interfere” with the original, but they call to question the very idea of an original. The two of them show us that an original is perhaps just a façade, that art is not made in intellectual solitude but through connections, molded together in community. Because translation is built on such connection, it becomes much easier to recognize it as a human act instead of a mechanical one.

The resulting collaborative text by Mngodo and Rubin is neither completely Swahili nor completely English, but exists on its own plane, free from the binary erasure of one or the other. It is filled with essences of both, challenging the implicit hierarchy that exists between languages. As such, I find this work not just exciting but revolutionary in paving a path for an experimental consideration of translation that centers both the author and translator. No longer a ghost or a one-sided witness, the translator becomes a co-creator, replacing the soliloquy with harmony.

Rebecca Suzuki is a Queens-based writer, translator, and poet. Her book, When My Mother Is Most Beautiful, was winner of the Loose Translation Prize and published by Hanging Loose Press in 2023. Her writing has appeared in The Los Angeles Review, Killing the Buddha, Riverteeth Journal, and other places. She teaches writing at Queens College, CUNY.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: