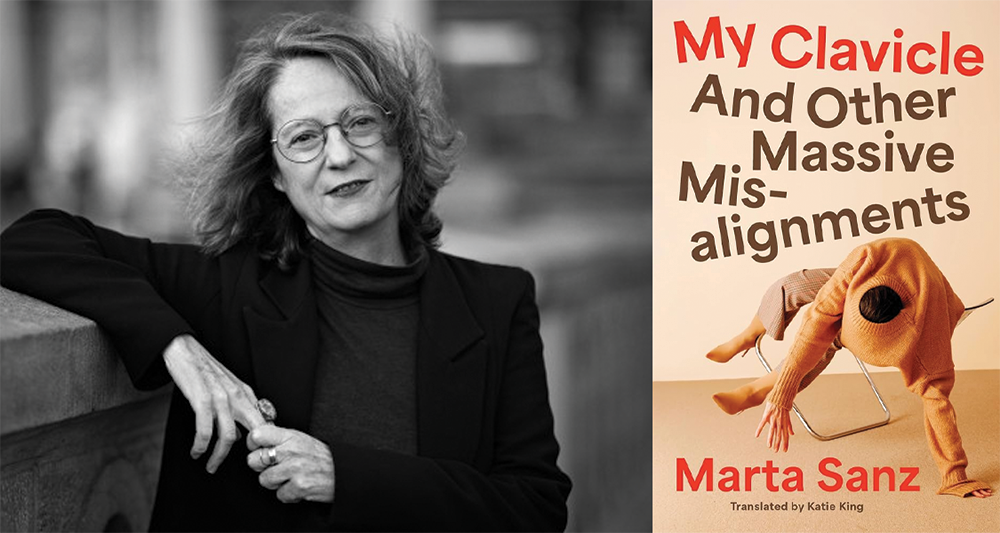

My Clavicle: And Other Massive Misalignments by Marta Sanz, translated from the Spanish by Katie King, Unnamed Press, 2025

In 2020, I was a postgraduate student amidst the COVID pandemic, writing my term-end assignment on Julia Kristeva and her concept of women’s time. Unwittingly, my professor had made a small typo in his materials; instead of ‘cyclical time’, he referred to the concept as ‘clinical time’. The term mystified us, and the entire class was held in a collective confusion in attempting to associate it with Kristeva. The error was later rectified, but not without arousing my interest; I was already thinking about the accidental ‘clinical time’, its importance magnified by the medicalised rhythm of the ongoing pandemic.

If Kristeva’s cyclical time is an indication of repetition and return, clinical time to me indicates a similar ebb and flow of a body in pain. Pain shapes time to be clinical; there is a surge and then a slump, affording the passing moments to be monitored and tracked and traded. In retrospect, the professorial mistake was actually a serendipitous slip that had already begun to align with my understanding of the physical world, an elucidation that was magnified when I encountered Marta Sanz’s My Clavicle: And Other Massive Misalignments. It was as if the error had already prepared me to read her work with a newer focus: to think of pain as a symptom as well as a diagnosis of misalignment, both physical and societal.

Translated from the Spanish by Katie King, Sanz’s (auto)fictive corpus maps pain, its anxieties, and its origins within and throughout the body. From the outset, the reader’s attention is made to focus on the almost biblical beginnings of pain. On a flight across the Atlantic to San Juan de Puerto Rico, the narrator—also named Marta Sanz—notices a bump on a certain rib under her left breast. She first sounds unsure as she ruminates over the pain, but this soon branches out to panic, aptly leading the prose through a precise recognition of the corporeal minutiae. She tries hard to dismiss the serpentine thoughts of eventual death by thinking of an aunt ‘who once went to the emergency room convinced that she was having a heart attack when actually it was just an attack of the farts’, but soon her pain-bearing thoughts overwhelm her, exacerbated by the caged space of the aeroplane, and of course the “bitch” Lillian Hellman’s memoir, which describes the cancer symptoms of her partner, the novelist Dashiell Hammett—symptoms which seem to resemble Marta’s own.

Between vulnerability and uncertainty, Sanz’s narrator emerges as one of us, one of our kind: an overworked woman in the age of late capitalism. She is certainly anxious about pinning down the cause of her pain, but the reason behind this urgency is the fear of ‘not being able to work’; sickness would keep her from paying the bills. As the sole breadwinner in her marriage, meeting expenses is hard, and being sick would make it harder. She then catalogues diseases, running through the medical histories of family and friends to determine the cause of her pain, but despite her efforts, the source remains enigmatic. Her gynecologist, pulmonologist, cardiologist, and rheumatologist all dispel her constricting fears, inducing her to ascribing an ‘ideological origin’ to her pain. This leads Sanz into settling the capitalist scale between the body and the soul, opening up My Clavicle into a critique of working conditions, the wellness industry complex, and the exhibitionism of the internet. Proteins, yoghurt, aromatherapy, yoga, cruising, pink notebooks, journalling—our narrator goes through it all, without making any real progress in ameliorating her pain. Despite all of this, what stands out most starkly is the ongoing world’s lack of concern for the individual’s body; life is expensive, bills have to be paid, and one has to perform even in agony.

I was particularly drawn to the narrator’s account of finding herself in a hotel room, with walls painted a lovely sky-blue hue, in the south of Spain. Arriving early in the text, this particular episode aptly sums up the horrors of succubus capitalism; her pain manifests as a tick that ‘will suck all the calcium out of my bones, as if my skeleton were a nutritious glass of milk or a freshwater spring. No one will come to help me’. The combined horrors of inhabiting a woman’s body in an exceedingly capitalist-driven and patriarchal society incites one to think if the pain voiced by anyone identifying as a woman could ever be considered seriously, and in addition to vivifying the discomfort and vulnerability of living in such a body, Sanz also painstakingly describes the tricky ordeals that plague the feminine form even beyond discomfort and illness. In an experience at a bar with an alcoholic (a universal experience cutting across geographies of the ‘first world, second world, third world, whatever you want to call it’), she spells out one of the many dangers that contribute significantly to the well-being of women, connecting this precarity to desire via a tirade against everything that gives an illusion of eternal biological or sexual productivity: a pill that awakens women’s sexual desire, lacey lingerie, the porn industry:

I abhor desire that’s artificially inoculated into a body when that body is preparing to sleep and slowly reach its end. I don’t want to function artificially. Salivating, lubricating, slurping artificially. There’s a moment in life when it’s good not to come anymore. You have to stop coming. I want them to leave me in peace. To allow me to forget about my body. For better or worse.

A self-proclaimed ‘DNA downer’, pessimistic to her core, Sanz is okay with her vagina slamming shut ‘like the cave of Ali Baba’s forty-thieves’. She’d rather open up blunt, honest conversations around women’s health—for example, menopause, a phenomenon at once accrued to the biological as well as the cosmological, which is carefully understood through her stream-of-consciousness writing. Sanz’s narrator is extremely hyperaware—and perhaps this is her shortcoming. Capitalism demands attention away from the body, for ‘work to deaden the pain’, but in its subtle and omnipresent pervasion, any focus on one’s own physicality can result in rumination and self-introspection—but also in pronouncing the logic of all the slick ideas being constantly marketed to us, ranging from the manufactured selfies populating the internet to the commercialisation of writing itself. As the narrator’s pain shapeshifts, so does the narrative, defying the chronology of time and the integrity of narrative structure to be read instead as ‘an investigation, a search’ while she attempts to get used to this new state of being, witnessing the transformation of the body into spectacle that further elucidates its context of watching and being watched.

Sanz’s work speaks through Katie King’s economy as a translator, and the latter’s extraordinary and yet subtle feat of maintaining puns and metaphors throughout the prose. Her deft hand is given a perfect metaphor in My Clavicle: ‘Writing makes everything just a little bit clearer by tidily tying the giant squid’s twirling tentacles with a red velvet ribbon, collecting the black ink it expels into the depths of the abyss, and organizing it into letters of the alphabet.’ King is the organizer, and she does so with imagination, boldness, and a powerful alignment of voices.

Ultimately, Sanz’s work is a litmus test to understand how women, their bodies, and their experiences are trivialised. Still, in an incisive comparison between herself and David Foster Wallace, the narrator remarks on the writer’s inability to enjoy himself on a luxury cruise, as well as his later suicide, ‘which is something I would never do no matter how many times some readers might ask why, or why not. It would be easy to do, of course. But throwing a tantrum about things that distress me does not equate to a desire to disappear. In fact, I don’t want to disappear. . .’. She goes on a cruise, and loves it. In this stage of late capitalism, the state of women can be no better than that of lobsters, set in cold water on a hot flame—and yet, one may continue to notice the illumination enshrined in the struggle, the way one metamorphoses instead of disintegrating: ‘I’m putting me back together again, top to bottom. I encase myself and all my jagged pieces in a cast. I am healing.’

Sonakshi Srivastava is a senior writing fellow at Ashoka University, the translations editor at Usawa Literary Review, and an educational arm assistant at Asymptote. Her writings have generously been supported by the 2024 ASLE Translation Grant, Director’s Fellowship (Martha’s Vineyards Institute of Creative Writing), Diverse Voices Fellowship, and the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts. She can be found on X and Instagram.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: