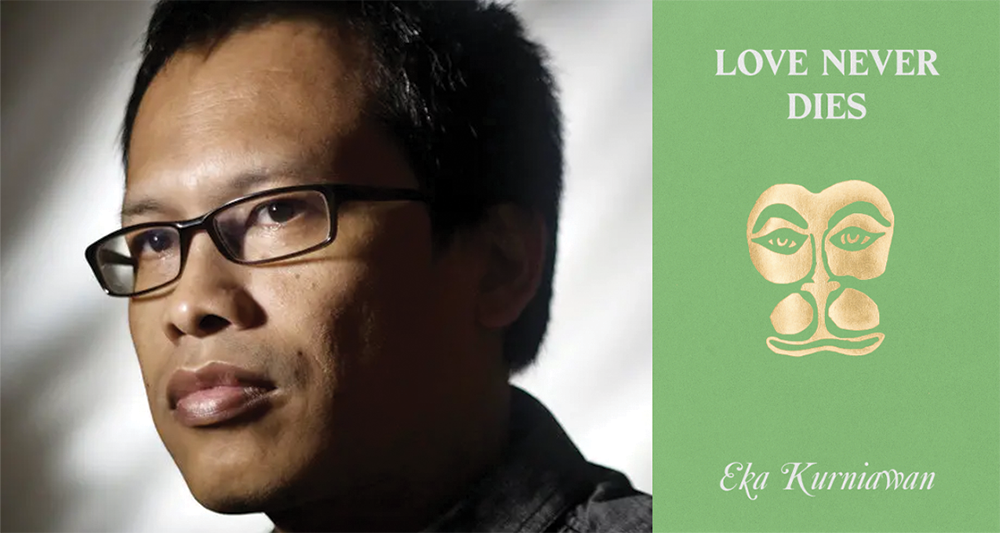

Love Never Dies by Eka Kurniawan, translated from the Indonesian by Annie Tucker, Hanuman Editions, 2025

The Indonesian writer Eka Kurniawan has been prolific in the novel form, having looked at the forces that negate death in Beauty is a Wound, translated by Annie Tucker, and the forces that create death in Man Tiger, translated by Labodalih Sembiring. However, while working on his third novel, Vengeance Is Mine, All Others Pay Cash (also translated by Tucker), the gifted author published two collections of short stories—the second of which begins with the novella Love Never Dies. Stripped of its surrounding stories, this novella is now appearing in English as a standalone volume.

Perhaps the choice to publish Love Never Dies separately was a choice made by Tucker, Kurniawan’s long-time translator, or perhaps by the publisher, Hanuman Editions—but either way, the text now appears more important in its English edition, as a volume on par with Kurniawan’s novels and a distinct step in the author’s career. Indeed, Love Never Dies should be considered as such. It cleanly synthesizes the themes of Kurniawan’s first two novels, determining that the forces creating and negating death are the same thing, and names that force “love”—or specifically, a man’s love toward a woman. From the first pages, it will be clear to any reader familiar with Kurniawan’s work that Love Never Dies is in conversation with its predecessors; Mardio, the seventy-four year old protagonist, seems to recall Margio of Man Tiger, and although the characters are different, the association between their names hints at the former’s future, and the murder predestined to take place at the novella’s end.

Mardio is, simply put, an incel. He’s spent sixty years lusting after and then being in love with the same woman, Melatie, who continually rejects him throughout their youth, then proceeds to marry a wealthy but selfless doctor. Despite her marriage, children, and grandchildren, Mardio loves Melatie to the extent of exhibiting physical symptoms. When a psychologist finally tells him: “Forget that woman . . . and start a new life,” the wording is telling. Kurniawan has created an unbreakable link between love and life.

After his visit with the psychologist, Mardio spies a twenty-year-old woman in the park, lusts after her, and then falls in love with her. He waits for this young woman at the park day after day, redirecting the force of his affections away from Melatie. Then, likely as a result of this, Melatie is killed in an accident:

At the crossroads, a billboard advertisement as big as half a volleyball field plastered with the image of a happy couple had toppled over into the street due to a brief storm, just as an old granny and her small grandchild were emerging from the supermarket and crossing the road. Like a flyswatter, the billboard smashed them flat.

The billboard that “toppled over” onto Melatie and her grandchild displayed a “happy couple.” Love, or specifically, the physical displacement of love, killed Melatie—that much is obvious from Kurniawan’s description of the event. Throughout Love Never Dies, it is this phenomenon—leading up to and following the death of Melatie—that Kurniawan explores: love’s destructive force.

Elements of magic exist within the structure of Kurniawan’s novella, but the supernatural of Love Never Dies is far more restrained compared with that of Kurniawan’s other work; here, it often seems to be relegated to metaphor, only rearing its heads in strange phrases. To swear “on the devil himself” is used once, then the common idiom “by the devil” sees further applications. Such unnatural inserts, subtly crafted in translation by Tucker, draw further attention to aspects of the occult.

“On the devil” is used when talking about Mardio, whereas “by the devil” is used in association with other characters, associating Mardio with satanic elements. He stalks Melatie “like a demon,” while Melatie, on the other hand, is often described as an animal, compared first to a pig, then a “tamed dog,” then a mouse. Unlike Mardio and her husband, she has few personality traits, and the short section Kurniawan wherein dips into her perspective is largely focused on her body:

On hellish nights, when the moon and stars were scattered into chaos by a witch’s broom, and the air became a vicious drowning river, the girl would lie under her blanket, huffing and snorting louder than a pig, a sign that she was thinking harder than the wise and clever. . .

Sitting naked before the mirror, stroking her own cheeks and chest with a gentle, devilish touch, she would wonder, is it really this body the man wants?

Before Melatie meets the doctor, she considers accepting Mardio—not because she loves him, but because she would be “giving up” and yielding to his force; as she contemplates this, she immediately takes on the “hellish,” “devilish,” and satanic descriptors usually associated with Mardio. His love directly pulls her to hell, to death.

When Melatie then meets her future husband, who is described to be “as tall as a god,” one immediately latches on to the differences between the two men. Heavenly and godly descriptors follow the doctor immediately, and Melatie is no longer “drowned”; she continues to live her life as an animal on earth, caught between the heavenly force of the doctor’s love and the hellish force of Mardio’s. Only once Mardio pulls his force away from Melatie does she lose her status as an animal. “Since becoming a corpse, the woman was now half-god. . .”; she leaves the earthly dimension, presumably for heaven. Mardio then wonders “whether he could hope to meet Melatie in heaven,” and seems to realize he won’t be able to. Thus, logically, the only option for him is to keep the force of his love on Melatie, and either “pray recklessly that God would return her to earth” as an animal, or redirect the doctor’s love away from her, so she no longer becomes “half-god” but half-devil, giving Mardio a chance to meet her in hell.

The masculine love portrayed in Love Never Dies transforms Mardio and the doctor—but Melatie as well. Mardio’s satanic epithets disappear from the text on two occasions: the moment he encounters Melatie for the first time, and during their first date at the movies. When Mardio first sees Melatie, she neither rejects nor speaks to him, seeming to accept his infatuation with her; she does nothing as he follows her home, “shuffling like a pig.” When Melatie then accepts Mardio’s invitation to go see a film, he is described “as a cock crowing.” On both occasions, there is no change in the feelings of either. Melatie only appears to accept Mardio’s directional love, and that quiet acceptance briefly transforms Mardio.

The doctor, once he begins a relationship with Melatie, is described as a “clever son-of-a-bitch,” and he and Melatie “reproduc[e] like mice” once they’re married. The choice of these idiomatic phrases in English pull the doctor’s angelic character down to earth. Melatie does not seem to love the doctor in the masculine manner Mardio loves her; she merely seems to find the doctor’s love easier—and more proper—to accept. She meets the doctor, imagines “the sight of them striding in together” to be “glorious,” and accepts his affection.

Female love, in the world of Love Never Dies, does not exist, or is negligible compared to masculine love, the changes of which can create cosmic imbalances. Mardio acknowledges this imbalance: “. . . he was the type to believe the stubborn love of a man could conquer the heart of even the most obdurate woman. . .”, and while the love shown to her has a permanent impact on Melatie, her acceptance of it leaves neither a permanent impact on the doctor nor Mardio; after her death, Mardio takes on even more demonic descriptors, and the angelic halo of the doctor returns: while visiting Melatie’s grave, the doctor’s shirt “gleam[s] as if there was light shining from every stitch.”

In this, Kurniawan portrays heterosexual love at its patriarchal, misogynistic extreme. The men of Love Never Dies, in order to be human, must have their love accepted by a woman, who in turn has little say in how she is being transformed by the male gaze, by unwanted male affection. Men are gods and demons, and in order for that to be possible, women must be unthinking, base animals. This strict hierarchy, of men as divine (or devilish) beings—of directional, possessive, and malicious masculine love—draws every character of Love Never Dies closer to death and destruction.

Within the limited structure of a novella, no frivolities or excesses can enter the system of Love Never Dies. Despite the fact that it builds on arguably ancient themes, Kurniawan’s words and Tucker’s translation are sudden, tight, and brimming with anger and passion. One may consider it a great entry point into Kurniawan’s other, more complex works; Love Never Dies creates and preserves a system, through which the living Indonesian master’s worldview is easily visible.

Ria Dhull is an artist and collector based in New York City. She reviews film for Spectrum Culture.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: