The story begins on November 28, 1975, the day the Portuguese colony of East Timor declared its sovereign independence. A little more than a week later, Indonesian troops invaded the island, backed by the American government and armed with American guns. Over the next three years, the Indonesian army, under the leadership of Muhammed Suharto, killed more than one hundred thousand East Timorese citizens. Most of them were unarmed civilians. The Timorese resistance continued, nonetheless, for the next twenty years.

On the same day East Timor declared its independence, Eka Kurniawan was born in West Java, just a few hundred miles away. He spent most of his childhood in the town of Pangandaran, where the only books he could find were horror comics, romances, or detective novels—three genres that clearly left their mark on his style. At Gadjah Mada University, he spent most of his time enjoying the translated works of Gogol, Melville, and Hamsun. He read almost no Indonesian literature, thanks to the Suharto regime’s strict program of censorship; however, he managed to get his hands on a copy of the Buru Tetralogy, the magnum opus of the great Indonesian novelist Pramoedya Ananta Toer. In 1998, Kurniawan completed a thesis on Pramoedya and graduated from Gadjah Mada. In May of the same year, as if on cue, Suharto resigned.

In his thesis, Kurniawan argued that Pramoedya’s brand of socialist realism had become politically obsolete, unsuited for an era in which the government’s barbarism defied comprehension. The novels and stories he’s penned in the last twenty years are often described as works of magical realism, full of matter-of-fact descriptions of monsters, ghosts, and resurrections. But his greatest disagreement with Pramoedya’s novels, with their methodical pace and chronological structure, may be in their representation of time. Curiously, Kurniawan depicts the passage of time in a way that suggests the circumstances of his own life. There are no “sad” or “happy” moments in his books; instead, each scene features a massive cast of humans, animals, and spirits feeling all manner of emotions. At the same time that a deadly invasion is beginning, a newborn baby is giggling. At the same time that a cruel tyrant is coming to the end of his career, an ambitious young novelist is starting his own. In one of the tensest scenes in Vengeance Is Mine, while the protagonist is being beaten in his prison cell, Kurniawan pauses to record the musings of a lizard crawling on the ceiling:

. . . my stomach hurts. Maybe that mosquito I ate hadn’t sucked enough blood. Pardon me, but my poop’s about to slither out and fall.Shit is everywhere in Vengeance Is Mine—it’s constantly pulling the characters down to earth, reminding them of their place in the world. More than a stroke of bathetic comedy, call this the crux of Kurniawan’s philosophy of time: at any given moment, no matter how poignant or terrifying, someone is shitting. Kurniawan seems to think of his job as that of a dedicated archivist, cataloging the scatological, the personal, and the historical with equal gusto. The results are often hilariously funny.

*****

The blind old man felt something cold splat onto his bald head. He touched it. Something mushy. He brought his fingertips to his nostrils. “Damnit. I knew it was stinky lizard shit. Why did I have to smell it?”

For Kurniawan, any given moment comprises an infinite number of events happening in the present tense. By the same token, every event in his novels seems to “contain” the prior events that have brought it about. In Man Tiger, Kurniawan’s second novel, the narrator spends the entire book unpacking the act of violence described in the first sentence: “On the evening Margio killed Anwar Sadat, Kyai Jahro was blissfully busy with his fishpond.” To solve the mystery of Anwar Sadat’s death, it is necessary to dip deeper and deeper into the past—first by understanding the events that led to the killing, then the events that led to those events, then the events that led to those events. A similar way of thinking about time underlies some of the most memorable parts of Vengeance Is Mine, for instance: “Years later, when he met Jelita, Ajo Kawir often remembered that day—the day he decided to marry Iteung.” We’re presented with two seemingly unrelated events, but over the course of the next chapter, Kurniawan will show how they’re closely connected—in fact, how one is inseparable from the other.

If that sentence sounds suspiciously like the beginning of One Hundred Years of Solitude, it’s surely no coincidence. The novels of García Márquez fascinated Kurniawan during his time at Gadjah Mada, and many critics have compared Halimunda—the little island featured in his first and longest work, Beauty is a Wound—to Macondo, the setting for One Hundred Years of Solitude. Like Kurniawan, García Márquez’s sentences often seem to join the present with the past and future, cramming as much time into as little space as possible. But while the temporal shifts in One Hundred Years of Solitude have an air of inevitability to them, those in Kurniawan’s books can come across as arbitrary and ostentatious, even when they’re amusing. Instead of rising to the level of a “perpetual epiphany,” as the literary theorist Franco Moretti wrote of García Márquez’s prose, they more often register as punch lines, delighting even when they don’t enlighten.

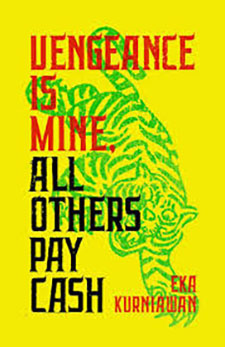

By depicting time in this way, Kurniawan’s novels run the risk of seeming needlessly jumbled. His experiments tend to be most successful, in Man Tiger and parts of Beauty is a Wound, when he gives them some kind of a structure upfront, so that there can be no ambiguity in the book’s subject or the period of time it covers. The opening sentence of Man Tiger is like a thin membrane stretched tight around the plot, ordering the abrupt shifts in time and guaranteeing that they have a greater part to play. Vengeance Is Mine is a looser work than its predecessors, frustratingly so. The endless tangents and stories-within-the-story hang inertly from the rest of the book, all but begging to be cut. Whole chapters, arranged non-chronologically, seem unnecessarily confusing, exercises in style without a greater purpose. The blurb on my New Directions paperback likens Kurniawan to Quentin Tarantino, and while the comparison is apt, Vengeance Is Mine most often evokes the late Tarantino of The Hateful Eight—the artist of unmemorable characters, repetitive dialogue, and dead-end flashbacks, who tests his audiences’ patience without giving them much in return.

Like much of the pulp fiction Kurniawan devoured as a child, Vengeance Is Mine features a young ruffian whose inner weaknesses lead him into a life of crime. As a teenager, Ajo Kawir witnesses a violent rape that leaves him unable to get an erection. Cursed with a “hibernating pecker,” as Kurniawan never tires of calling it, he tries to distract himself by fighting other boys, then by working as a hired killer for a gang, and finally by becoming a truck driver. His love interest, Iteung, is a young martial arts prodigy. A long, bloody fight between them doubles as a courtship and ends with the same short, curt sentences that characterize the novel as a whole:

Not far from Mister Lebe’s fishpond, Ajo Kawir was lying with his head resting in Iteung’s lap. She bent down to hold him tight. She wiped the blood from the kid’s nose. She caressed his face. Ajo Kawir reached up to return the caress, wiping the tears from Iteung’s cheeks. Again and again, Iteung lifted Ajo Kawir’s head and kissed it.

“What are you going to do with a guy who can’t get hard?”

“I’m going to marry him.”

Even the late Benedict Anderson, one of Kurniawan’s most passionate champions, was forced to admit that his protégé still had a lot to learn about characterization. Iteung is typical of Kurniawan’s female characters: she’s extraordinary in every way except her relationship with the male protagonist. In this respect she’s cut from the same cloth as the heroines of Touch of Zen and the various other wuxia films Kurniawan enjoyed as a teenager. By contrast, most of the men in Vengeance Is Mine are blandly forgettable. Many of their exchanges (“I don’t want you to die.” “I don’t want to die either. So I won’t.”) suggest a hard-boiled Samuel Beckett.

On closer inspection, the dialogue and characterization in Vengeance Is Mine aren’t conspicuously worse than those in Man Tiger or Beauty is a Wound. Man Tiger dispensed with dialogue almost entirely, and neither of the two earlier works gave its characters much of what the critic James Wood called “inner life”—the illusion of psychological depth that has been, despite some notable opposition, a fixture of the modern novel. But in these earlier works, the absence of so many of the novel’s usual features felt justified by Kurniawan’s radical rethinking of time, dramatized in sentence after lively, playful sentence. Vengeance Is Mine offers something altogether different, something between pulp and experimental fiction but without the pleasures of either genre.

Annie Tucker, who previously translated Beauty is a Wound (Man Tiger was translated by Labodalih Sembiring), does what she can with Kurniawan’s prose, but can’t iron out the tics and repetitions in the original Indonesian. Passages have an irritating habit of doubling back to correct themselves:

He thought he lost consciousness after slamming onto the ground, or if he didn’t lose consciousness, he lost track of how long he had been lying there.Gone, too, is the inventive vocabulary for which Anderson celebrated Kurniawan; in Vengeance Is Mine, kisses “smolder,” memories are “crystal clear,” and lovers feel a “burning flame” in their chests (at least until they’re “stabbed in the heart”). Even the book’s centerpiece image fails to inspire much poetry: the hibernating pecker is soft, sleepy, and little else.

He still wasn’t at all interested in the idea. Or more precisely, he pretended he wasn’t interested.

The woman was ugly [ . . . ] or rather she was still ugly, but her ugliness seemed to excite him strangely.

It’s likely that Kurniawan is paying homage to the choppily written crime stories he grew up on, rather like Tarantino tipping his hat to the B-movies of his childhood. But strangely, he embraces the lesser aspects of the genre (weak characterization, cheesy dialogue) and ignores what’s most praiseworthy about it (the careful pacing and concision). Part of the problem may be that hard-boiled fiction, with its endearing gracelessness and unique slang, is one of the hardest genres to translate. In a fascinating essay published in 2001, the Spanish academic Daniel Linder describes the dilemma of translating Raymond Chandler: one can literalize Chandler’s hyper-American slang and risk rendering it almost incomprehensible, or one can find non-idiomatic equivalents and risk making the prose sound more unwieldy. It’s possible this is the same problem Tucker faced while working on Vengeance Is Mine. Passages that may have conveyed a rough poetry in their original language have become merely rough—for example, “The truck drivers had their own way of solving any problems that arose amongst them” (though why Tucker, a native New Yorker, chose the clumsy and slightly archaic-sounding “amongst” is another story). Many Indonesian idioms appear to have been omitted in the interest of comprehensibility, leaving only those that are common in both Indonesian and English—hence all the clichés.

In the early 2000s, at an age when many creative geniuses are slaving away in anonymity, Eka Kurniawan was already being touted as his country’s greatest living writer. Vengeance Is Mine shows him still grasping for a mature style, wrestling with a different set of literary influences—not the magical realist milestones he enjoyed in university but the cheap thrillers that made him fall in love with reading in the first place. In doing so, he’s torn away the scaffolding that held his early work together; what’s left, it turns out, isn’t much.

Coincidentally or not, the shift in Kurniawan’s style comes at a time when magical realism has achieved cultural saturation, when almost every new English-language book or film or TV show has a dash of fantasy thrown in for good measure. (What else do Mad Men, Birdman, and City on Fire have in common?) Too often, the technique seems like a fad and nothing more. Certainly, we’ve come a long way from the glory days of the 1960s, when García Márquez used it to convey truths that ordinary realism could not. Like Pramoedya’s socialist realism before it, magical realism has lost most of its political efficacy, so Kurniawan shouldn’t be faulted for trying something different. If Vengeance Is Mine is a failure, it may prove to be what Martin Amis, describing James Joyce’s play Exiles, called a “big, necessary failure”: a bold but inept experiment that provides its author with the raw materials for another, better book. Joyce’s follow-up to Exiles, after all, was Ulysses.