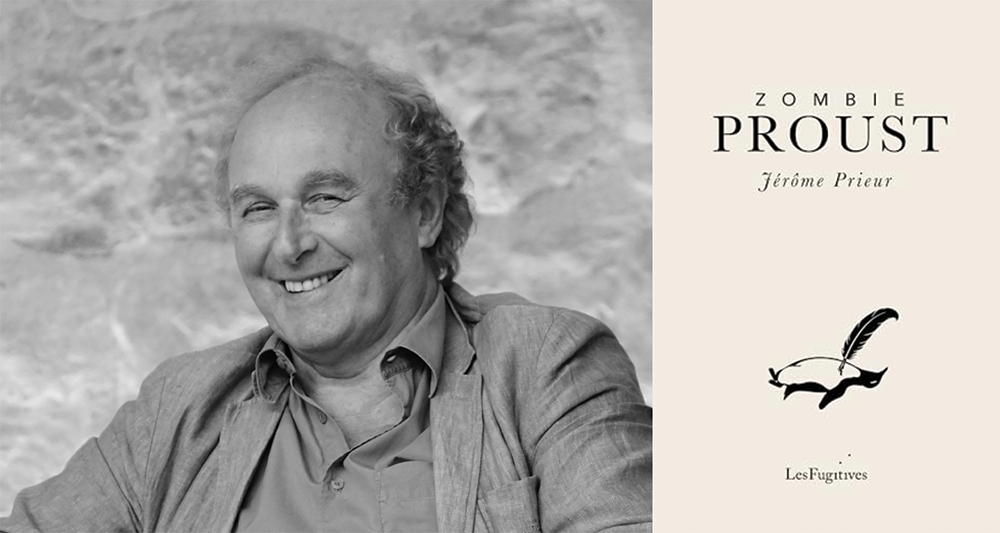

Zombie Proust by Jérôme Prieur, translated by Nancy Kline, Les Fugitives, 2025

“Marcel Proust was never filmed at all,” asserts Jérôme Prieur in Proust fantôme, his 2001 French text rendered into English by Nancy Kline in 2025 as Zombie Proust. In 2017, however, a Canadian professor claimed that he had found Proust’s moving specter in the silent footage of Countess Élaine Greffulhe’s 1904 wedding to the Duke de Guiche. Entering the frame about 35 seconds in, Proust, or his mustached double, wearing a pearl-gray overcoat, black vest, and black bowler hat, looking somewhat less formal than the other guests and in a hurry, descends the stairs, overtakes some older folks, and exits the frame.

The discovery of this possible Proust, occuring in the interval between Prieur’s originally published text and its translation, seems to be especially meta. Whenever we talk about Proust and his seven-volume novel, In Search of Lost Time, there exists always a splintering tension between chronological and subjective recollections, motion and stillness, analogous to the temporal, spatial, and linguistic gaps between an original text and its translation. In short, there are many ways to interpret Prieur’s statement that Proust “was never filmed,” just as there are many ways to read Zombie Proust.

Prieur, Proust scholar, film-maker, and actor, could be defined as an archaeologist or detective in search of Proust’s ghostly imprints in the 21st century. French critic Norbert Czerny referred to him as a “chiffonnier [who yearns] to restore to past objects the energy they once possessed.” Imbued with gothic élan, chiffonier—rather than its earthy rendering in English as “rag-and-bone man” or “scavenger”—allows us to imagine Prieur as someone in pursuit of time’s silken, disintegrating threads.

But while Prieur endeavors to follow Proust’s traces, his project is an existential exercise that seems to question its own gestures of homage to Proust. Implicitly acknowledging Proust’s warning that a conscious, deliberate act of recall—defined as “voluntary memory”—could yield sterile or distorted versions of the past and its subjects, Prieur understands that any creative or critical response that does not renew or expand the public’s understanding of Proust’s century-old legacy runs the risk of becoming banal and superfluous. Prieur recounts, for instance, how a clerk who doubled as tour guide at 102 Boulevard Haussmann—Proust’s former residence now operated as a commercial bank—would cheerfully offer its customers mass-produced madeleines individually-wrapped in cellophane pouches.

To avoid the literary equivalent of these soulless madeleines, Prieur defines his search for Proust’s restless phantom, rendered in 72 mini essays or compressed prose poems, as an allusive and immersive quest. By seeing through Proust’s “eyes/I,” Prieur retrieves his narrator Marcel’s involuntary memories from In Search of Lost Time: the uneven paving stones from the Guermantes’ courtyard which in turn trigger the memory of uneven paving stones in the baptistery of St. Mark’s Cathedral in Venice, and telling traces from Marcel’s childhood bedroom at Combray:

The cracked tiles beneath our feet in the miniscule passage that never ends, the wall still splashed with the projection from the magic lantern, the imprint of a neck on a feather bolster, the first floor of the summer home on the Rue du Saint-Esprit, the childhood bed, still made up, untouched, like the interior of a little tomb. . . . What the writer’s eyes saw, what his senses perceived, it is these that mesmerize and lure us in pursuit of him, until we finally wonder just how far we can go in our turn, which footsteps we can walk in.

These allusions to Proust’s novel represent the real madeleines—creating a sense of panoramic movement of the writer’s universe—infinitely more palpable and dreamlike than their literal replicas entombed in plastic at 102 Boulevard Haussmann, thus transporting the reader back into Proust’s cyclical, loamy text.

Prieur’s concept of Proust as a phantom—as opposed to Kline’s zombie metaphor in the English translation—affirms Proust’s idea of shifting dualities that are inherent in all of his characters and in Marcel’s perception of time. Specifically, Proust’s monumental novel seems to have been influenced by Oscar Wilde’s Picture of Dorian Gray, in which the protagonist’s physical beauty, like a mask, remains outwardly untouched by time while his hidden portrait reflects both the ravages of time and his inexorable desires. Likewise, in evoking Proust’s celebrated portrait painted by Jacques-Émile Blanche, Prieur compares Proust’s historical photographs to “youthful masks,” whereas his fictional oeuvre—which took the writer over a decade to complete, and most likely cost him his life—reflects “an evolving Proust, presumably aging, but eternally true to himself.”

In Proust’s time, the French word for gay or queer is “inverti,” from the Latin invertere, meaning to “turn upside down, upset, reverse, transpose,” and figuratively, to “pervert, corrupt, misrepresent.” Thus, the reverse of a positive (or socially acceptable) image is its negative, i.e., a latent, truthful, but terrifying, or socially unacceptable portrait. The young Marcel detects this ghostly self, full of suppressed longings, in Charles Swann:

For what other lifetime was [Swann] reserving the moment when he would at last say seriously what he thought of things, formulate opinions that he did not have to put between quotation marks, and no longer indulge with punctilious politeness in occupations which he declared at the same time to be ridiculous?

In Search of Lost Time: Swann’s Way, tr. Lydia Davis

Proust’s In Search of Lost Time (which could also be called In Search of Phantoms) also represents the inverse—pun intended—of Kafka’s Metamorphosis. If Kafka externalizes Gregor Samsa’s otherness as a monstrous arthropod to frontally challenge conventional ideas about familial love and communal acceptance, Proust, like Wilde, internalizes his character’s otherness, showing how this alien nature only emerges in spontaneous, unconscious moments. Accordingly, a person’s love or appreciation for a double-faced character would inexorably implicate them, for their emotional attachment reflects their uneasy compromise, motivated either by self-interest or self-denial. For example, in Swann’s Way, while young Marcel appreciates his family cook’s culinary talent and tireless devotion to his family, he also knows that she unflinchingly slaughters chickens and mistreats other household servants. Acknowledging that everyone has to make “cowardly calculations” to get along with others, Marcel incisively deduces that external beauty often masks inner suffering and violence, just as “history reveals that the reigns of the kings and queens who are portrayed with their hands joined in church windows were marked by bloody incidents.” (Swann’s Way).

Proust’s portrayal of his characters’ inherent otherness—this otherness that brings them undue shame or embarrassment when manifest—actually infuses them with a mysterious vitality. Similarly, in the essay “Likeness,” Prieur shows us that the search for the true self represents the desire to embrace one’s inalienable strangeness:

Under the pretext of viewing the body, it is the enigma of the character we wish to catch sight of . . . . The secret is that of likeness. But likeness in the paradoxical sense . . . [To French critic Jean Paulhan], “accurate photos, faithful portraits can be powerful, subtle, beautiful or ugly … [but] they don’t resemble us . . . . ” [W]e cannot see and recognize ourselves in any known physical form, not as portraits represent us . . . . But only as ghosts.

Prieur’s idea (via Paulhan) of the elusive, invert double dovetails with Marcel’s eternal search for the fleeting multiplicity of Albertine, his Platonic other half:

. . . [I]t was my fate to pursue only phantoms, creatures whose reality existed to a great extent in my imagination; there are people indeed—and this had been my case from my childhood—for whom all the things that have a fixed value, assessable by others, fortune, success, high positions, do not count; what they must have, is phantoms. They sacrifice all the rest, leave no stone unturned, make everything else subservient to the capture of some phantom …. It was not the first time that I had gone in quest of Albertine, the girl I had seen that first year outlined against the sea . . .

In Search of Lost Time: Sodom and Gomorrah, tr. C. K. Scott Moncrieff, Terence Kilmartin, and Dennis Joseph Enright

In surveying the various iterations of the phantom explored in Proust’s expansive novel and Prieur’s minimalist yet revelatory text, it would have been pretty straightforward to translate Proust fantôme as Phantom Proust, or even Proust’s Ghost. Why, then, has Nancy Kline opted for Zombie Proust? At first, it could seem like a cynical or strategic move to make the book more commercially viable, at the risk of distracting prospective readers with involuntary visions of cordyceps-infected ambulatory corpses. Upon reflection, however, Kline’s choice of “zombie” as an interpretive response to Prieur’s “fantôme” is brilliantly apposite. In an interview with Asymptote in 2019, Kline, an astute translator, discussed how her native New Yorker accent intuitively influences the texture of her translation, as in the tonal shift between her “Nuptial Face” and a colleague’s more formal “Nuptial Countenance” in transposing René Char’s poem Visage Nuptial into English. In this case, as in that one, it appears Kline has good reasons to turn Proust fantôme into Zombie Proust.

Just as there are complementary or overlapping shades between “fantôme” and “zombie,” there exist many parallel or interactive dualities in Proust’s novel: the duality between a visible body and an invisible, elusive, phantom soul; the duality between the contemplative, cosmic plain of Swann’s Way/Méséglise and the history-bound river realm of The Guermantes’ Way (see how both names evoke their inherent essence, as “Swann’s Way/Méséglise” points toward transcendence, and “Guermantes’ Way” ironically suggests “gourmand”—a rapacious or “junkie” appetite for gossip and social connections); and the duality between desire and possession.

In both Proust’s life and work, if desire reflects an internal process—the exaltation of one’s beloved or cherished milieu as a response to uncertainty or loss—then possession represents an external, corporeal, invasive quest—the overwhelming need to devour the world and enslave the beloved, hence Kline’s attribution of a zombie nature to Proust. Even in Proust fantôme, Prieur sees this glaring contradiction in our author: Proust the sensitive artist who glimpses sheltered truths in his characters is also a vermicular tube mercilessly suctioning information from his surroundings, constantly demanding to know “all there is to know, idle rumors, gossip, genealogical trees, the history of every church tower in Île-de-France ….” According to Prieur, Proust would insist that people send him esoteric information, such as “the origin of [a print design] found on Fortuny fabric, or the exact rules governing the Japanese game of floating origami.” A prodigious reader, Proust often ingests, seemingly at random, volumes of the social registry, encyclopedias, train tables, Balzac, Flaubert, Stevenson, and Baudelaire.

For all his meandering sentences and striking metaphors, such as the way he successively compares the Martinville church steeples—from the vantage of a horse-drawn carriage galloping down twisty country roads—to flitting birds, golden spinning tops, painted flowers, and lost little girls trapped in a fairytale twilight, Proust’s portrayal of his social environment is ruthlessly precise. The raw material for his gargantuan novel, accreted from gossip, eavesdropped conversations, surveillance of neighbors and socially prominent friends or associates, is regularly procured by Proust’s and other people’s servants acting as his paid informers.

Possession of privileged information was as important in Proust’s days as in our own. (In Swann’s Way, Tante Léonie, a stand-in for Proust, is a homebound hypochondriac who achieves her omniscience, and omnipresence, via her paid “eyes” and “ears”—represented by the lame Eulalie and the cook Francoise.) Proust’s voracious need to collect information as a means to achieve literary power resulted directly from his socially precarious situation. While coming from an illustrious upper-middle-class background, Proust, half Jewish, queer, asthmatic, insomniac, and unemployable, was generally considered “out of time.” Prieur calls him “the invisible man” who “dreams of infinite entrances, of causing hidden doors to open to him, of ransacking drawers, [and] cracking safes, knowing the most well-guarded secrets.”

Like Tante Léonie in Swann’s Way, Proust viewed his sickly condition as both acquiescence and resistance, rejecting a normative life and what we would call “ableist” expectations, to collect the necessary marrow for his all-consuming art. Consistent with Kline’s zombie interpretation, Prieur writes that Proust saw glittering Parisian dinners and costume balls as “great massacres.” His society models posed for him and were in turn “devoured” by him without their awareness. His muses became “guinea pigs on whom he tested out his hypotheses [and] fantasies,” as Prieur observes. In addition, Proust had the help to supply him with a steady diet of piquant secrets. Thus it’s abundantly clear that Kline’s zombie interpretation does not reflect a calculated or shallow take on Prieur’s fantôme, but rather, thoughtfully incorporates Prieur’s specific examples of Proust’s ravenous hunger for other people’s lives.

Céleste Albaret, Proust’s housekeeper, could arguably be considered a zombie whose soul was willingly pledged to Proust. Twenty years his junior, and, in her own words, Proust’s voluntary prisoner, Céleste also acted as his surrogate mother, cheerleader, playmate, scapegoat, editor, mouthpiece, ambassador, and valet. Labeled by critics as femme inculte (“unplowed” or uncultivated female), Prieur writes that Céleste, true to her name, existed as Proust’s “wings, his life, and his last link to the daylight.” Outliving Proust by over six decades (she died in 1984), Céleste kept Proust’s memory alive with Monsieur Proust, a trenchant account of her years with the writer, leading a life as regimented as “music paper” but also completely spontaneous. While one could say Céleste’s living body remained haunted by Proust’s spirit long after his death, Prieur inverts the nature of Proust and Céleste’s collaboration:

[A]fter his death, the secrets he has confided to her will far outsell Swann, Guermantes, Sodom et Gomorrhe, and the rest. Just the thought of reversing their roles must have filled him with joy: she the writer, he the model; his life—his most quotidian, most ordinary life—the subject of her book.

Prieur’s view of Celeste’s role as Proust’s co-creator, rather than his passive vessel, reminds me of Bình, the gay Vietnamese protagonist in Monique Truong’s novel The Book of Salt. Fleeing his family in French-colonized Vietnam, Bình becomes the live-in cook for Gertrude Stein and her companion Alice B. Toklas in pre-World War II Paris. Outwardly polite and taciturn, Bình is in fact a wry interloper and social critic who assiduously records the unguarded moments of his so-called free-thinking “Mesdames.”

In other words, Prieur’s text, while purportedly excavating Proust’s life and his literary legacy, actually celebrates the complex, alchemic collaboration, not only between the artist and key individuals in his orbit—family members, chauffeurs, cooks, housekeepers, lovers, and society personnages—but also those who either outlive him or are born years after his death, even living in farflung countries or continents.

Thus Prieur’s statement that Proust “was never filmed at all” can be taken to mean that this author, with his iconic mustache and sleepy Mona Lisa eyes, has continuously resisted being captured as a historical image or defined as a monolithic presence. Despite, or precisely due to his all-encompassing shadow on the literary landscape over the last hundred years, Proust has been refracted, assimilated, and reborn into a multitude of other texts, other voices, other faces, other skins, and other fates. Most importantly, Proust shows us that the secret to literary immortality is empathy:

The only true voyage, the only bath in the Fountain of Youth, would be not to visit strange lands but to possess other eyes, to see the universe through the eyes of another, of a hundred others, to see the hundred universes that each of them sees, that each of them is.

In Search of Lost Time: The Captive, tr. C. K. Scott Moncrieff

Proust’s Whitmanesque ideal I/eye contains multitudes, and it is this multiplicity that Prieur, in Zombie Proust, seeks to recover, finding Proust’s phantom images through his fathomless, eternal eyes.

Thuy Dinh is coeditor of Da Màu and editor-at-large at Asymptote Journal. Her works have also appeared in Words Without Borders, diaCRITICS, NPR Books, Prairie Schooner, and Rain Taxi Review of Books, among others.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: