“Children,” Jan Dost tells us, “grow up quickly in wars.” In his bold and unflinching Safe Corridor, the author demonstrates this brutal reality through the eyes of a young narrator caught within Syria’s civil conflict, resulting in a phantasmagorical, gripping account that not only captures the violent facts, but also the mind’s attempts to accept them. As Dost moves seamlessly between the surreal, the absurd, the tragic, and the enraging, the novel engages with the true consequences and aftermaths of loss: who—or what—one becomes after surviving the unthinkable.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

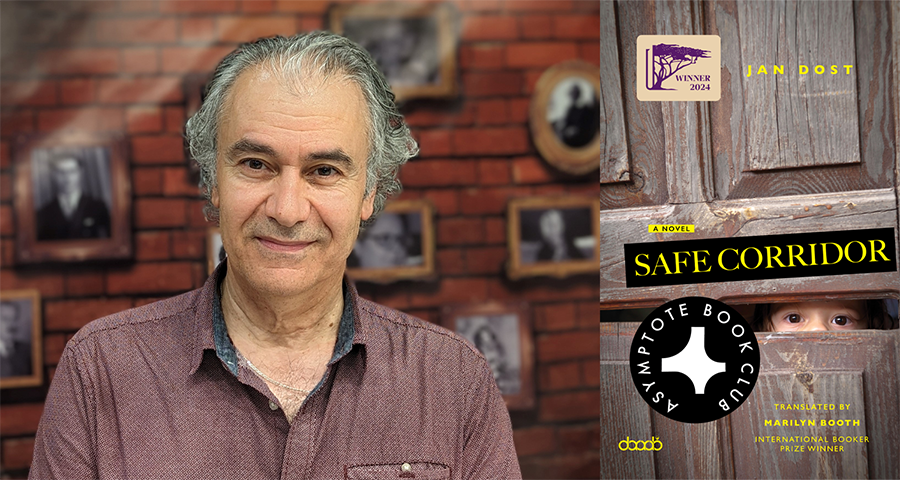

Safe Corridor by Jan Dost, translated from the Arabic by Marilyn Booth, DarArab, 2025

“On the evening when young Kamiran began to realise that he was turning into a lump of chalk, rain was bucketing down.” With this devastatingly surreal image, Jan Dost’s Safe Corridor—gracefully translated by Marilyn Booth—immerses its readers in a scene that brings to mind Kafka’s The Metamorphosis. A Syrian-Kurdish writer-translator based in Germany, Dost is one of Syria’s most important living authors with sixteen novels to his name, most of which center the realities and consequences of his home nation’s civil war. Safe Corridor, originally published in Arabic in 2019 as Mamar Āmin, entrusts this testimony of a devastated country to a voice least equipped—and yet most fated—to bear it. Told through a fragile, furious, and often surreal narration, the novel captures how war is not only fought on battlefields but also inscribed upon the bodies and imaginations of children. As the acclaimed Palestinian poet Mahmoud Darwish puts it in his poem “The War Will End”:

I don’t know who sold our homeland

But I saw who paid the price.

Roland Gary, in his introduction to Kafka: A Collection of Critical Essays, states that the Czech writer’s work “belongs unmistakably to the twentieth century . . . because his sense of man’s fate is deeply bound up with the atrocities and nightmares of the age.” Similar atrocities have persisted into our own century, ensuring that Kafka’s worlds remain an enduring source of inspiration for many writers worldwide—especially Arab novelists. They are the worlds of the absurd, marked by estrangement and fear, wherein one is perpetually hounded by unseen forces they cannot name, condemned to live within utter futility.

Amidst Safe Corridor’s war, the child has become the historian, recording what adults try to forget. The novel unfolds through the eyes of a thirteen-year-old boy, Kamiran (Kamo), whose name means “the one who’s blessed with luck,” and follows his scattered family. The patriarch, Kurdish physician Farhad, has long been held captive by ISIS/Daesh, and the ones left behind are thus forced from bombed-out city to camp, from camp to street, seeking a way that might ensure survival. The journey is framed as a desperate search for safe passage, though the title itself feels like a bitter joke; the safe corridor never materializes. Instead, it is Kamiran’s narration itself that becomes the passage—narrow, precarious, lined with the rubble of lives that war has reduced to whispers.

Whereas Gregor Samsa of The Metamorphosis is horrified to find himself transformed into a grotesque insect, the transformation in Safe Corridor marks not the beginning but the culmination of young Kamiran’s ordeal. Instead of horror, Kamiran feels an immense relief—even joy—at turning into a giant piece of chalk, as if he no longer wishes to belong to a world that has forfeited its humanity in the face of war’s horrors. He refuses to remain part of a brutal reality that has outstripped even imagination.

Throughout the novel, chalk—usually associated with the classroom—is given the symbolic weight of witness: a material fragile enough to crumble yet capable of carrying memory. Dost repurposes an everyday object into a testament of war, absorbing his young narrator’s account of massacres, displacements, stolen dreams. Kamiran confides his secrets in his little piece chalk, naming it “Safra,” and in return, it listens unconditionally, offering Kamiran a space to narrate experiences often overlooked by distracted adults. Thus, chalk reflects the fragility of childhood in crisis, burdened with the heavy weight of remembrance, and with it, Dost creates a chronicle of devastation that feels both intimate and collective, within which words are not only the storyteller’s tools, but also their negation.

By handing the story to Kamiran, Dost aligns himself with a long tradition of war literature told through children’s eyes—from Jerzy Kosinski’s The Painted Bird to Ahmed Saadawi’s Frankenstein in Baghdad. But Safe Corridor pushes this further, collapsing the child into his medium. Kamiran does not merely recount the war, he becomes the instrument by which it is written. The result is a book that does not insist on the healing potentiality of narrative, but on its ability to call attention to the ever-persistent scars.

Kamiran, burning with rage at the conflict that stole his father and caused his sister to be “sliced in two by an exploding barrel on her birthday,” narrates his family’s horrible journey with equal parts bitterness and raw defiance. His testimony vividly illustrates a memorable cast of characters, linked by their experiences of loss. There is his mother, Layla Aghazadeh, who remains silent despite speaking four languages; an uncle, Ali, who plays the bouzouki and uses music as a form of resistance; a woman named Mazyat, who wages her battles in the intimacy of her own bed; and elders who mourn the dead while holding onto keys to homes that may be forever lost. Kamiran himself is also racked with loss—even his beloved green bicycle is seized by one of the extremist militants accompanying the Turkish army during the invasion and occupation of Afrin, a Kurdish majority city in northern Syria. After Kamiran’s house is taken over, the soldiers loot everything inside, and the loss of the bicycle therefore comes to represent not only the loss of a childhood innocence, but also the theft of a dream and a homeland.

Safe Corridor is punctuated with surreal eruptions as Kamiran rides his bicycle, climbs into his uncle’s truck, and dreams. In one scene, an old woman—named Zallukh— transforms into an olive. As her wrinkled body merges with the land itself, Kamiran describes:

She became a dark green ball, and she rolled across the ground like a huge American football, after she’d rolled over and fallen out of the trailer while everyone watched, utterly dumbfounded and terrified.

In another, trees sprout backward beneath the returning displaced, as if time itself were rebelling against exile:

Then I noticed that the olive-tree shapes that I had seen in the mud as he walked away were rising straight up. They were turning into trees. After every step that left behind the image of an olive sapling, there was a tree shooting up from the ground.

These moments are not distractions from war, but its truest expressions. Where adults may reach for rational reportage, the child aims for metaphor because it is the only vessel wide enough to contain catastrophe.

Still, in the end, even Kamiran’s words fade, swallowed by the noise of shelling, retreating behind the roar of mortar fire. The novel beautifully circles back to its start, inviting us to reflect on a thought-provoking question: Amidst conflict, can there ever be a safe corridor that preserves the distinctions between child and soldier, olive tree and concrete wall, prayer and bullet? As Kamiran narrates in the final scene:

I was melting. I was disappearing. Soon, I wouldn’t exist. I was vanishing completely, so how could my father claim that there was no such thing as non-existence? What was it, if it wasn’t a big piece of chalk dissolving in floodwaters? And then, this surging stream of water carrying me would mingle with all the rivers that went on and on out here.

Marilyn Booth does superb work in her translation, which is well deserving of the inaugural Bait AlGhasham DarArab International Translation Prize. In her thrilling, vivid prose, the novel reads as a scream against war, launching a barrage of curses at all parties involved in the conflict. Kamiran’s words—his swearing, his eruptions, his fury—resound with the thunder of indignation, giving only a partial but necessary impression of the real-life devastations.

However, labeling Safe Corridor merely as a “war novel” feels almost too tidy; it is more accurately a book of open wounds. In it, olive groves are bleeding red and the skies are tinted green with the shadow of conflict. Poetry fuses with the grotesque, and tragedy is a blatant fact. Cutting right through the hollow terms of humanitarianism that distort the reality of violence’s true cost, Dost instead uses a child’s raw curses to convey the obliterating truth:

Fuck the War.

It stole everything from me. . .

Ibrahim Fawzy is an Egyptian writer and literary translator working between Arabic and English. He holds an MFA in Literary Translation from Boston University and both a BA and MA in Comparative Literature from Fayoum University, Egypt. Fawzy’s translations have been featured in various literary outlets. His accolades include a 2024-25 Global Africa Translation Fellowship, a 2024 PEN Presents Award, and the 2024 Peter K. Jansen Memorial Travel Fellowship from ALTA.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: