The Last Soviet Artist by Victoria Lomasko, translated from the Russian by Bela Shayevich, n+1 Books, 2025

The title of this review is part borrowed from, and part inspired by a subsection of Svetlana Boym’s The Future of Nostalgia. A meditation that concerns itself with the capacious titular affect, Boym studies nostalgia through the revolutionary era of perestroika, the fall of the Soviet Union, and well into the present. While she categorizes two types of nostalgia, restorative and reflective—the former more active, seeking to reconstruct the past, and the latter passive, dwelling in yearning—she caveats that these are only “tendencies, ways of giving shape and meaning to longing.” While reading Victoria Lomasko’s The Last Soviet Artist, a third degree of nostalgia emerges: the residual. Nostalgia’s escape from the decay of romanticization towards a productive politic of collective and self-exploration feeds the heart of the text.

Translated from the Russian by Bela Shayevich, Lomasko’s latest—a graphic reportage that blends elements of memoir—was initially planned as a sequel to her Other Russias, which she mentions in her introduction. I hold a particular reverence for introductions; these precise portals often reveal more of the author’s motivations than is written on the surface, and Lomasko’s is particularly transparent. There is an urgency—we learn that Lomasko has self-exiled in response to Russia’s iron grip of heavy censorship and repression. In her home country, there is no room for imagination, no space for artists, and social activism has been systematically stifled. This realization dispels the awe Lomasko had held for “those fairytale pictures and stories” that she grew up reading about an everlasting friendship among the fifteen Soviet republics. Any remaining traces of nostalgia for “that period” soon erode away when Lomasko, seeking photocopies of her work clandestinely at a museum in Belarus, realizes that her body remembered what it “had really meant to be a Soviet person.”

The Last Soviet Artist is strung within the matrix of time and space—the axes of nostalgia—and divided into three parts. The first part, written before the COVID-19 pandemic, is an organic graphic assemblage of her travels to the “post-Soviet space,” the former Soviet republics that she could visit before travel was restricted. Aptly titled “Traces of Empire,” these detailed portals into the socio-cultural and political situations of post-Soviet countries begin in 2014, when Lomasko was invited by a local feminist group in Kyrgyzstan as an art instructor. Early in the text, a subtle tension between Kyrgyzstan and Russia is spelt out through their minding of “I” and “Y” in “Kyrgyz”: to place an emphasis on “i” in “Kirghiz” implies that one “has gone totally Russian and forgotten their people’s traditions.”

In Yerevan, Lomasko encounters a picture of generational conflict distinct to many of the other post-Soviet nations she had visited. Despite the homogeneous composition of the country, where criticism has to seep through the cracks and the saying “Turks will always be Turks” holds ground, the youth throw caution to the air in promoting Turkey’s leftist movement. Lomasko encounters the son of the famous socialist artist Simon Galstyan, who turns out to be a committed critic of the Russian language and culture, as well as their imposition upon the Armenians during the Soviet era. In contrast, a brief comic relief unfurls when an older local is disturbed by Lomasko’s drawing of the headless Lenin statue that was decapitated during perestroika, asking her to keep it hidden.

Further folds of inter- and intranational tension stretch out into Dagestan, where women are treated as commodified lesser beings, there is a lack of financial support for second wives, and female circumcision and minor girls being married off to older men are far from uncommon. Lomasko faces the chequered past of Dagestan through her meeting with Sirajuddin Abdurakhmanov, the author of On the Hairpin Curves of Our Lives, who called for the Russians to acknowledge the forced deportation of Dagestanis as a historical fact. This “local history” is not minor, for it festers in inherited memories of the Dagestanis. Even as much of the country renounces Russia’s actions, a few vestiges of reflective nostalgia linger, such as the great-uncle of Lomasko’s host, who “respects” Stalin’s politics and regime.

In Georgia, Lomasko meets Soso, a former lieutenant in the KGB who boards and leads tours at Stalin’s Underground Printing House Museum. For the older population, the museum is a nostalgic ode that has withheld the passage of time, a signifier of could-have-beens. Lomasko reports that “70 percent of Georgians believe that they would be better off living in Russia than in Europe or America”; they fancy having a president like Putin. Her stay in Tbilisi is bookended with an illustration of Oleg, a former journalist from Moscow, that encapsulates the sense of reverence and lingering nostalgia that she encountered while in Georgia.

In the following sections, the locus of Lomasko’s attention shifts from other people to herself. In Ingushetia, a student provides a rare insight into the scale of relative independence for women, and Lomasko is drawn to reconsider her position as a Russian woman. Back in Kyrgyzstan, Part I comes full circle in Osh, apparently an “apolitical town,” which in some circles made inter/national news during the (bare) coverage of the violent 2010 conflict between Kyrgyzstanis and Uzbeks. It is here that something shifts for Lomasko: despite her admiration for Vasily Vereshchagin, the first Russian orientalist artist, she is “repulsed” to learn of his actions during the conflict; he traded his brushes for rifles, and took an active part in suppressing local revolts. With this sense of conflict, questions about the functions and responsibilities of art begin to stir within her, nudging her focus away from the centrifuges of memory and nostalgia towards their impact on herself as an artist.

In Part II of her work, “The Last Soviet Artist Becomes Someone Else,” Lomasko presents an intimate and sustained understanding of her own life and her positionality as an artist. Lomasko is at her best in this section—life drums through the pages, and there is a tangible shift in tone as landscapes and mentalities turn grimmer, the pandemic grows graver, and burgeoning protests pepper the pages. In Minsk, artists are arrested for resisting Alexander Lukashenko and surveillance is heightened. Lomasko, who has been part of the protests herself, is “scared” by the “brutality” of the Minsk police against the protestors. She, like many, runs away, and protests are abandoned. With such an onslaught of brutality, any remnants of sentimentalism and nostalgia are stripped away, “washing away the traces of everything Soviet like so much flotsam.”

Throughout the book, Lomasko’s interactions with artists from post-Soviet nations serve as points of reflection and expansion in her own self-understanding. She meets Nadia Plungian, whom Lomasko had once resented for staying away from protests. This encounter quietly shifts something within her; she comes to see that the artist’s task is not only to bear witness, but to “draw the outlines of the future she wants to see, helping to manifest it.” This realization gives way to her final portrait, one of herself. She looks back at her “reporter-artist” endeavors in shame, likening them to her father’s hated task of painting propaganda. There is a fantastical rupture in her vision as she parts from the “tedious Last Soviet Artist” for whom “political developments were more important than the first flowers coming up in the courtyard.” From here, Lomasko desires to bloom independently.

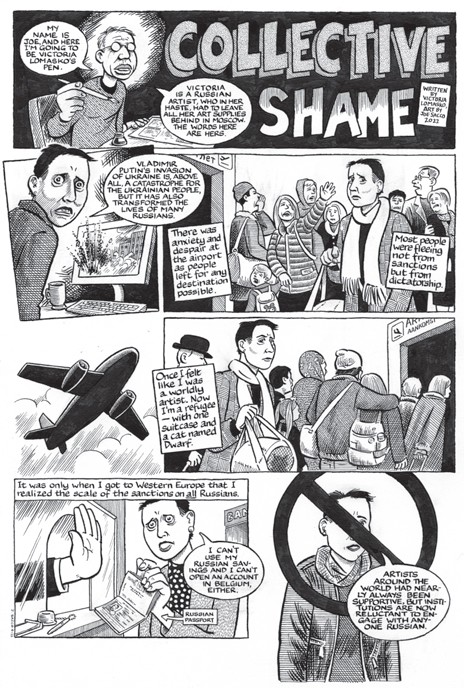

In Part III, “Exile,” Lomasko illustrates her last sketch “at home.” She has been declared a foreign agent. Moscow is under snow, and the snow will not melt for Lomasko. Unable to draw her own comics, Lomasko entrusts Joe Sacco to become her pen in “Collective Shame.” Through her words and his illustrations, Sacco depicts the morbid ordeal that Lomasko endured not only during her flight as Russia began its war on Ukraine, but also while living under the weight of being declared a foreign agent.

She poses a question that pierces the heart of The Last Soviet Artist: “What choices are there. . . for someone caught between Putin, shame at the war, and what feels like Western rejection of all Russians?” Reading calls for travel restrictions on all Russians in the news, Lomasko is compelled to reflect on the graces of solidarity and friendship that she had received from different institutions and individuals throughout her earlier travels. She concluded: “. . . there’s room for an artist or a writer everywhere. The entire world is mine by birthright.” Creativity cannot and shall not be chained. It requires no restraints of space or time to flourish. It refuses to back down in the face of concerted efforts of authoritarian regimes. It blooms and has the right to bloom in any state.

The Last Soviet Artist depicts Lomasko’s journey from an aesthetic inertia rooted in residual nostalgia to an electric sort of momentum. In the closing pages, Lomasko returns to the idea that amid all the hopelessness and hardship, the only glimmer of hope lies in the recognition that humanity is “composed of unique individuals,” and that it is through this recognition that we move toward “collective progress.” She is neither sentimental nor “envious”; she is capable of deep introspection and self-reflection, and these qualities are imbued throughout The Last Soviet Artist.

In The Art of Translation, Vladimir Nabokov defines a fine translator as someone who has “as much or at least the same kind of talent” as the author, who must “know thoroughly the two nations and the two languages involved,” and most importantly to his mind, must be “able to act, as if it were, the real author’s part.” Bela Shayevich’s translation is an exceptional rendition of an exceptional artist’s work, and inspires a fourth quality for the ideal translator: one who is able to ignite curiosity among the readers. The Last Soviet Artist compels readers to take note, to research, and to reflect alongside Lomasko.

The Last Soviet Artist is an urgent read for the incendiary times that we inhabit today, and a critical response to the aesthetic inertia of our times. Lomasko’s latest is a work that urges you to question your position.

Sonakshi Srivastava is a senior writing fellow at Ashoka University, the translations editor at Usawa Literary Review, and an educational arm assistant at Asymptote. Her writings have generously been supported by the 2024 ASLE Translation Grant, Director’s Fellowship (Martha’s Vineyards Institute of Creative Writing), Diverse Voices Fellowship, and the Alkazi Foundation for the Arts. She can be found on X and Instagram.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: