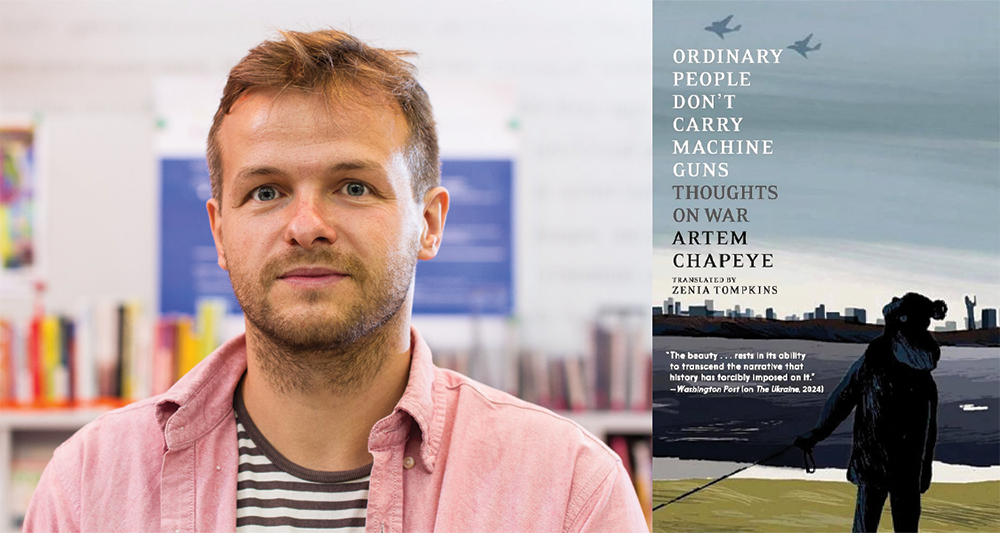

Ordinary People Don’t Carry Machine Guns by Artem Chapeye, translated from the Ukrainian by Zenia Tompkins, Penguin Random House, April 2025

Since Russia’s full-scale invasion of their country, Ukrainian writers have brought the resistance into their language. Some who once worked in Russian have switched to Ukrainian; others stopped capitalizing the invader’s name, rendering it as puny russia (росія). This is about reducing Russia, ejecting it from a language it has tried to claim as its own, as if in anticipation of Moscow’s physical expulsion. In his latest book—equal parts memoir, treatise, and document of the first three years of the invasion—Artem Chapeye rejects not only Russia, but the cruel logic of war. Throughout Ordinary People Don’t Carry Machine Guns, Russia—and the grief, fear, uncertainty, guilt, and shame its war brought upon Ukrainians—is referred to as “Gloom.” It is Gloom that encroaches upon Ukraine, Gloom against which Chapeye, who joined the military shortly after Russia invaded, takes up arms alongside his countrymen. Gloom is both Russia’s literal tanks and missiles and the psychological conditions Russia’s invasion forces upon Chapeye—at once the monster and the terror it inspires. Yet Ordinary People does more than chase Russia from its language. Chapeye, rendered in affable English by Zenia Tompkins, resists the affect of war itself. Through Tompkins’s frank translation, which favors a colloquial, musing style, Chapeye remains irrepressibly human as Gloom tries to change him. The result is a surprisingly warm and compelling text that insists on rising above Russia’s war, even as it acknowledges the urgency of the real-world struggle to end it.

Chapeye, a four-time finalist for BBC Ukraine’s Book of the Year Award, a fiction writer, photographer, activist, and now soldier, divides Ordinary People into three sections, each mixing memoir, history, and Chapeye’s relentless inquiry into the war. The first, “When Gloom Encroaches,” retells the days leading up to February 24th, 2022 (referred to by Ukrainians, Chapeye tells us, simply as “the 24th”) and Chapeye’s decision, unexpected even for himself, to enlist in the armed forces. The second section, “We Must Cultivate Our Garden,” begins as he joins his unit and transitions to a new life at war. The line between “Garden” and the final section, “People Can’t Be Separated Into Varieties and Breeds,” blurs as war becomes normal—more normal than the days Chapeye is off-duty or allowed to visit his family. Throughout the entire text, Chapeye reflects on his life in the armed forces, the friends he makes in his unit, his country fighting for its existence, and the world peering in—all in a candid and approachable voice that preserves Chapeye’s prodigious curiosity and capacity for empathy, even as Gloom attempts to strip both from him.

If Ordinary People documents literal resistance to Russia’s invasion, its language does the same on a linguistic level. Zenia Tompkins’s translation insists on Chapeye’s humanity, his intelligence, his natural kindness in unnatural times. Tompkins—a major translator of modern Ukrainian literature, whose previous projects include Stanislav Aseyev’s memoir/investigation The Torture Camp on Paradise Street and fiction from Tanja Maljartschuk (Forgottenness) and Chapeye himself (The Ukraine)—renders Chapeye’s affable Ukrainian in familiar and conversational English. Descriptions of one day at war bring up memories of others, or remind Chapeye of the life he’s left behind, or summon uncertainties about himself or the world at large as he wanders from subject to subject. Reading Tompkins’s translation, it is as if we are hearing, after so long, from an old friend who does not know quite where to begin. So when “whatevers” and “or somethings” and “on the other hands” abound, the feeling is less one of doubt and more one of comfort and familiarity. Sentences trail on as Tompkins lets Chapeye’s thoughts unspool naturally in English: “In my opinion, soldiers are, conversely, becoming, I don’t know, somehow gentler or something.” Tompkins preserves his humor—his references to Marvel movies and his nicknames for some particularly odd fellow soldiers—even as the text takes stock of its dead, or marks the transformation of villages to battlefields, and fathers and sons to soldiers. The melding of Chapeye’s grim sense of humor, his intelligence, and the very real circumstances he now finds himself under is especially clear in moments like these, where Tompkins manages to preserve all three:

“There’s a Ukrainian joke that used to be funny but became sad on the twenty-fourth. A villager is asked, ‘Why does your wife toil in the garden, and wash the dishes, and take care of the children, and look after the livestock, while you sit on a bench in front of the house in the meantime and smoke?’ The villager exhales cigarette smoke and, in a phlegmatic voice, answers, ‘What if there’s a war, and here I am tired?’

But now, a war really had arrived.”

The cumulative effect of Tompkins’s translation is its own sort of resistance: a constant reminder that, under tremendous pressure and uncertainty, in the face of evil, Chapeye’s voice still sparkles, familiar even for those who haven’t read him.

A more ornate style might echo the Cossack folksongs and Ukrainian anthems, whose nationalizing power Chapeye doubts. Chapeye’s emphasis on the down-to-earth manifests even in the titles of its various renditions: in Ukrainian, the text is called Не народжені для війни, literally Not Born for War, but it was first published in French in 2024 as Les gens ordinaires ne portent pas de mitraillettes, or “Ordinary People Don’t Carry Machine Guns.” The Ukrainian and English versions release simultaneously this year, with the Ukrainian maintaining its original title and Tompkins mimicking Iryna Dmytrychyn’s acclaimed French translation. Each title has an effect (and affect) of its own, but Tompkins’s final translation feels right. Ordinary People Don’t Carry Machine Guns, with its juxtaposition of the pre- (“ordinary people”) and post-invasion (“carry machine guns”), echoes the juxtapositions Chapeye is writing about in his own life. Not Born for War reads more like a novel’s lyrical title; it recalls lost innocence, the quiet goodness of being “born” against the dramatic violence of “war.” Tompkins’s English title, beyond resembling a version of the book that performed quite well, also preserves Chapeye’s conversational tone. This book is, after all, about ordinary people fighting a Gloom that has forced them to carry machine guns.

Ordinary People is at its best when Chapeye’s prewar ordinariness—his creativity, his capacity for empathy, his conviction in his role in the world—run up against Gloom and the brutal “practicality of history.” Here, Chapeye resists through inquiry, through embracing the uncertainty that Russia’s invasion has summoned within him. Rather than letting Russia and its war demolish his values, he observes how his beliefs have shifted over the course of the war. Despite his self-described pacifism, and his long skepticism of nationalism, Chapeye enlisted in the military a day after Russia invaded the rest of Ukraine. He’s turned over the results in his mind ever since. Gloom, to Chapeye, is so obviously evil—“almost metaphysical” in its “unambiguous injustice”—that he has a duty to resist it. Yet he’s “tormented by guilt” when he considers the family he’s left behind. He’s alarmed when Ukraine’s national anthem, for the first time in his life, gives him chills on the front lines. And as he, “probably one of the best-known male feminists” in Ukraine, leaves his wife and two young children behind, he watches as “the chthonic power of Gloom once against impose[s] a traditional division on the roles of man and woman: The man goes off to war, and the woman takes care of the children.” How should he reconcile his views with the realities around him? How can he reckon his stances before the war—his feminism, his admiration of Western intellectuals who now tacitly support Russia, his doubt in nationalism—with his perspective after?

Gloom would not have Chapeye ask these questions at all. The logic of war would demand only that he fight. By focusing on the ambiguity of his new life at war, Chapeye resists Russia’s invasion on a psychological level. With a pointedly casual register and sharp narrative structure, Chapeye’s relentless inquiry forms the defiant core of Ordinary People Don’t Carry Machine Guns—a text that, by recounting its author’s battle against Gloom, has joined the fight itself.

Sam Bowden holds degrees in English and Russian from Kenyon College. He is an Assistant Fiction Editor at Asymptote.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: