Pedro Lemebel, the iconic Chilean activist, essayist, and artist, wrote only one novel in his lifetime: My Tender Matador, a gloriously romantic narrative of repression, radicalisation, and infatuation. It tells the story of a trans woman—named only as the Queen of the Corner—and her brief love affair with a leftist guerilla named Carlos, taking place amidst the waning years of Augusto Pinochet’s brutal regime. Juxtaposed with comic passages that satirise the shallowness and greed of the dictator and his wife, the novel is a bold expression of selfhood and resilience that incisively wields Lemebel’s entrancing prose against the ugliness of tyranny.

Nearly two decades later, in 2020, Rodrigo Sepúlveda took this subversive novel to the screen, with Alfredo Castro starring as the exuberant Queen. Commenting on the material’s continual legacy and relevance, the director decisively noted Lemebel’s revered status and pivotal role: “If civil unions exist today and gay marriage is being discussed in Chile, it’s because of how Lemebel fought during the dictatorship.” One year after the film was released, Chile passed its legislation of marriage equality with an overwhelming majority.

In this edition of Asymptote at the Movies, we discuss these two works in conversation, conjunction, and deviation, with the mediums of literature and cinema making their distinct determinations on the narrative’s conceptualisations of beauty, politicisation, and imagination.

Michelle Chan Schmidt (MCS): My tender matador! From the original Tengo miedo torero, Katherine Silver gives us an English title that preserves sound over literality, with the Spanish meaning something more like: ‘I’m afraid, bullfighter.’ These beautiful [t] and [m] alliterations anticipate the lush whirl of images that unfurl in both Pedro Lemebel’s 2001 novel—’Like drawing a sheer cloth over the past, a flaming curtain fluttering out the open window of that house in the spring of 1986. . .’—and Rodrigo Sepúlveda’s 2020 film adaptation.

Like Silver’s title, the film’s opening scene translates Lemebel’s plot for beauty over ‘faithfulness’: the scene is Sepúlveda’s own creation. It starts in media res with a drag performance in a discothèque in Santiago, Chile—all sequins, jewel-toned light, and close-ups of the enraptured, laughing audience. They include our protagonists, the Queen of the Corner and the young, mysterious, militant Carlos, who meet for the first time later that night when he saves her during a police chase.

Talk about an elegant set-up: Sepúlveda effectively foregrounds the story’s central conflicts—on both personal and political axes—within the context of queerness and resistance in Pinochet’s authoritarian Chile, in less than a minute and in a setting that Lemebel did not write, but left to the reader’s mind. The beauty of Sepúlveda’s translation for the screen, a medium that serves visibility, hearing, and action, is also its concision. What other methods have you noticed Sepúlveda use to translate Lemebel’s text? How else has My Tender Matador molded to film?

Xiao Yue Shan (XYS): It’s interesting that you draw focus to beauty first, Michelle—it’s actually an aspect that I felt was so disparately depicted between the text and the film, for which the foremost consideration is the phenomenological difference of beauty as experienced between reading or viewing. Lemebel’s text is gorgeous in every way; not only is he a master stylist, but here, he takes special exuberance in writing scenes that are opulent, dazzling, and more importantly, ostentatious—especially when we are locked into the Queen of the Corner and her view of the world. It’s a radical depiction of queer presence and actualisation because it asserts that to be beautiful, to feel beautiful, and perhaps even to be seen as beautiful, is a necessary pleasure and a fundamental component of human existence—and therefore the novel dispenses with any aesthetic normalisation or expectation, including those associated with gender. As such, via the medium of language, we really are liberated from the burden of our predetermined notions of visual beauty and guided into a beauty that resembles more that of music: a beauty that stirs us, invites us, and convinces us of itself. We can’t help but see everything the way that the Queen sees it, the ‘nameless dirty alleyways she managed to transform into tropical sidewalk paradises with her swishing footsteps that clicked to the rhythm of the night. . . .’ For the most part, she is our guide, and much of Lemebel’s My Tender Matador is filtered through her ‘baroque imagination.’

Whereas photography, in the words of Andre Bazin, ‘affects us like a phenomenon in nature.’ Any beauty we glean from that image is inseparable from what we find beautiful in real life. I did notice that the first scene was lovely, as you mentioned, Michelle, but to me it was beautiful in that it was touching and emboldening: a reprieve of expressionistic joy during an era of deadly oppression and intolerance. Still, I couldn’t help but recognise that it was a derelict space, small and cramped; that the clothing was worn formidably but was not lavish or decadent; and that the environment was surreptitious and concealed, carrying with it a sense of dread. To me it was not a declaration of beauty, but a set-up for destruction—which happens only a couple minutes into the scene. It is very much a part of the concision you mentioned, the need to set the narrative ground and to substantiate characterisation, but it also fortified that adjustment of perspective demanded by the photographic image, which is to revoke imagination from our visions. The fact is that the true reality of My Tender Matador (that is, the reality of being a Queen in Pinochet’s Chile) is not beautiful; it’s harsh, brutal, dangerous, and it reminded me as a viewer that to be beautiful in our reality is in essentiality to be ‘agreeable.’ Sépulveda’s film portrayed this well, but while watching it, I was reminded again and again that what Lemebel does so successfully in his novel is to create a most convincing testimony of beauty, one that speaks to beauty’s only true definition and moral potential, which Simone Weil described very well, that ‘the love of the beauty of the world . . . involves . . . the love of all the truly precious things that bad fortune can destroy.’ I wonder if either of you sensed this as well?

Georgina Fooks (GF): I love that we’re opening with the question of beauty, because I think it’s so central to Lemebel’s aesthetic and political aims. Tengo miedo torero is one of my favourite novels, and at first, I was nervous to watch the film precisely because of the beauty of the prose and its ability to evoke such clear images. Lemebel truly stimulates the image of our imagination, painting beautiful pictures of radical possibility for trans and travesti people—for locas, or queens as they appear in Silver’s English translation. The power of the prose is to create a language of beauty for the Queen’s experience that can transcend our physical reality, and time and time again, the Queen repurposes the most mundane materials to make beauty, in what for me is a prime demonstration of camp resistance. For example, the birthday party that the Queen throws for Carlos is a divine example of insisting on aesthetic abundance at a time of increasing vulnerability and precarity: ‘the balloons, all of them purple, royal blue, canary yellow, and flaming red, most of all red because I think that’s what Carlos will like.’ Lemebel insistently offers the reader visions of a radically different reality, without the restrictions of a concrete image.

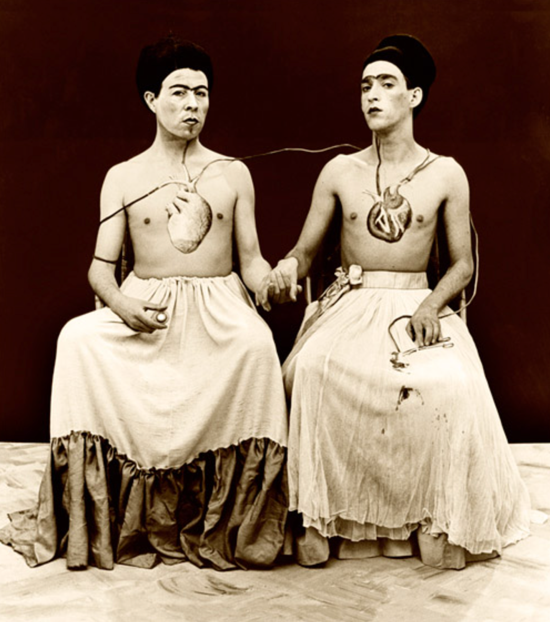

Lemebel clearly also believed in the power of the image (together with Francisco Casas, their performances as The Mares of the Apocalypse / Las Yeguas del Apocalipsis envision all kinds of queer futures), but the film does have to contend with a material reality that cannot be fully banished by the imagination.

Las dos Fridas, 1989

In this sense, the opening scene of the film is an effective way to foreground the political context, even if the Queen of the novel would like to ignore it: ‘she wasn’t quite there in the political fray. It frightened her just to listen to that radio station that reported only bad news.’ As the novel progresses, it too makes clear that the politics of the time—in more ways than one—seek to make the Queen’s existence an impossibility. The film captures a greater sense of political urgency, whereas the novel begins with violence in the hazy periphery, narrated mostly through snippets of sound:

A city waking up to the sounds of banging pots and pans and lightning blackouts, electric wires dangling overhead, sputtering and sparking. Then total darkness, the headlights of an armored car, the Stop, you piece of shit!, the gunshots, and the terrified stampede, like metal castanets shattering the felt-tipped night. Gloomy nights, pierced by shouts, by the indefatigable chant of Now he will fall! Now he will fall!, and the many last-minute news bulletins broadcast over the airwaves by Radio Cooperativa.

I’m curious to know what you both made of the Queen’s political engagement, both in the film and the novel, and whether you feel the adaptation had a slightly different aim to Lemebel’s text.

MCS: I love the points you both raised: the testimony of beauty that Lemebel creates, and beauty as camp as anti-authoritarian resistance, propelling the story forward through the tension between the queer, resplendent beauty that the Queen creates from mundanity, and the devastation her beautiful dreams—and reality—suffer at the hands of Pinochet’s government. What is the difference between dreams and reality? As you both wrote, the film sets beauty up to heighten the drama of its destruction, and yet we know that it will prevail: the code to Lemebel’s radical politics is that of beauty as possibility, as choice, as life.

I think of Lemebel’s ‘Manifesto (I Speak For My Difference)’, translated by Sergio Holas-Véliz and Israel Holas Allimant in 2015: ‘But don’t speak to me of the proletariat / Because to be poor and queer is worse,’ wrote Lemebel in 1986. This manifesto aligns with the Queen’s political positionality, which is verbalised much more explicitly in a scene of conflict between the Queen and Carlos, about two-thirds into Sépulveda’s version:

THE QUEEN: I did this for you. Nobody else. Because this country has always been ungrateful to me. Us queens don’t care about who’s on top, whether it’s military, or communist . . . Whatever. For them, we’ll always be a bunch of fucking fags. If there’s ever a revolution that includes us, let me know. I’ll be there, front row.

Out of her love and attraction for Carlos, the Queen stores ‘boxes of books’ and ‘rolls of very valuable manuscripts’ on his behalf, while also hosting ‘study sessions’ for his ‘friends from the university.’ The first mention of these boxes in Lemebel’s novel slowly come into focus, like a scene over which a camera pans and zooms back into time:

Thus the great care she took in adorning the walls like a wedding cake, populating the cornices with birds, fans, flowering vines, and lace mantillas draped over the invisible piano. Those fringed scarves, sheer nets, laces, tulles, and gossamers covering the boxes she used as furniture. Those heavy boxes the young man she met at the neighbourhood store asked her to keep in her house, that good-looking boy who asked her for a favour. Telling her they were just books, censored books, he said, through lips like moist lilies.

And Lemebel builds a brilliant pseudo-dramatic irony out of the Queen’s persona itself. Carlos’s membership of the Manuel Rodríguez Patriotic Front, founded to overthrow Pinochet’s dictatorship as the Communist Party’s military wing, is pretty obvious to everyone involved, including the Queen—and we can all make informed guesses at what these boxes actually contain. But to maintain her actuality, not only as a lover but as a Queen who is invested in the queer margins of Chile’s political discourse rather than the politic itself, she throws herself into her role of ‘magnificence’ until he spurns her beyond pretence:

Did he think she was a fool as well as a queen, a mere warehouse for storing boxes and mysterious packages? Did that little shithead really think she didn’t know what was going on? All those meetings of bearded men in her house. Did they have that much to study? Imagine that!

XYS: The Queen’s political engagement really is a fascinating point of discussion, because I think Lemebel does something extraordinary, narratively, by illustrating the dichotomy of radical presence—which is the Queen’s uncompromising frivolity, romance, and opulence—and radical action, embodied by Carlos and his compatriots and their guerrilla plot. One would presume that the two are part and parcel of the same schema, but it’s not so; inhabiting a politicised body does not (and should not) necessitate one’s participation in political action, and most importantly, as the quote that Michelle points out illustrates (‘If there’s ever a revolution that includes us. . .’), rebellion and resistance are formed out of the unified experience of repression. Revolutions depend on people being able to see their I reflected inside the we, but the we has also always been an exclusive conjecture. After all, if there’s a we, there’s a them.

So what Lemebel’s My Tender Matador does is very interesting. It takes an I who has been historically alienated from the we, and puts that self in a position to say: Maybe I can fight for them anyway. The underlying radicalism of this thought is something that the Chilean populace iterated through their 1988 referendum, which voted Pinochet out of office—in that instance, the people did not rally around the idea that they had been hurt in the same way, or that they shared the same past, but that they desired a different future. It reminds me of something said by the civil rights activist Dr. Berenice Johnson Raegon: “You don’t get fed a lot in a coalition. In a coalition you have to give. . .” Which is to say, you don’t fight alongside other people for your vision of the perfect future, you do so for the possibility that things will get a little bit better somehow, for somebody.

By instating a scene of mortal danger right at the beginning of his film, Sepúlveda leans more emphatically towards the fact that trans people should be included in the resistance, because they are explicitly targeted by the regime. It seems to me like a simpler and more pointed vision of what coalition politics presumes, resulting in a piece that aptly portraits the dictatorship’s oppression—whereas I feel that Lemebel is more interested in the process of radicalisation as a romance. The feeling of having your eyes opened to the facts of your reality, of finding an ideology that explains your pain, your alienation, and promises you that it does not have to be this way . . . It’s very much like falling in love. I was reminded a lot of Vivian Gornick’s The Romance of American Communism, wherein she writes:

It is perhaps hard to understand now, but at that time, in this place, the Marxist vision of world solidarity as translated by the Communist Party induced in the most ordinary of men and women a sense of one’s own humanity that made life feel large; large and clarified. It was to this inner clarity that so many became not only attached, but addicted.

That radiance and that ardour is what marked My Tender Matador for me. I interpreted Carlos almost as a personification of the beliefs and conviction he harboured: a gorgeous, idealised articulation of freedom, boldness, and promise that is seductive on every level. And we can see that both Sepúlveda and Lemebel want to accentuate how Carlos makes the Queen feel more alive, more brave and more awake, but also that the love is hopeless, unrequitable. It gives the ending a particular poignancy; the Queen is left alone, stripped of her home and her community, for all who throw themselves into the potential of an ideology are ultimately abandoned or betrayed by it. Still, she is changed, and her knowledge is precious but inglorious. The gift that ideology and romance gives us is only ever a period of vividity that cannot, in its very nature, last.

I’m also curious about what you both think about Sepúlveda’s choice to leave out a major section of the novel, which constitute the chapters written from Pinochet’s point of view.

GF: The difference between the film and the novel’s portrayal of the Queen’s political engagement, to me, feels like a difference of genre or mode. Sepúlveda commits to a realist mode of cinema from the beginning, which is a powerful choice in the current Chilean context, where it can still be controversial to articulate the full nature of the crimes of the dictatorship (and there are efforts on the right of the political spectrum to downplay or minimise those atrocities). The recent fallout from the attempt to reform Chile’s dictatorship-era constitution—a lengthy process with multiple drafts that ultimately ended up ratifying Pinochet’s document—was a salient reminder that the past is still very much present, and this history is all too recent. In that sense, there was a directness to Sepúlveda’s approach that I can see being very effective. The scene that you mention, Michelle—‘Us queens don’t care about who’s on top, whether it’s military, or communist. . .’—is not present in the novel, but it acutely articulates some of the concerns that play out in Lemebel’s life and writing. Lemebel always had connections in the Chilean Communist Party—he was a longtime friend of Gladys Marín, former secretary of the Party—but it was never an institution to which he could belong. The novel ends with the spectre of Cuba for this reason: a promised paradise for revolutionaries like Carlos that was never going to accept someone like the Queen. The film, however, prioritises differences within the movement from the very beginning.

Given the film’s realist style, it therefore feels relevant that Pinochet’s perspective does not appear in the film. There’s a sense that this could be as simple as streamlining the narrative—Sepúlveda’s choice heightens the emotional drama of the Queen and Carlos’ relationship—but in turn, loses some of Lemebel’s satire and bite. The chapters written from inside the Dictator’s mind are some of the most humorous and incisive parts of the novel, and I love Lemebel’s choice to incorporate this perspective as I see it embodying his camp resistance to the full; he queers the novel of dictatorship, an established literary genre, and makes Pinochet reside within a novel that the dictator himself would hate. In Spanish, the word for gender and genre is the same—género—and in the Queen’s subversive presentation of her gender, so too is the genre of the novel subverted. In that sense, Lemebel’s treatment of the Dictator is hilarious. The First Lady’s stylist is described as ‘that priss Gonzalo,’ a prominently camp figure in Pinochet’s inner circle, and the First Lady’s monologue on the dictatorship’s appearance ridicules Pinochet in both its banal, nagging style and superficial content:

Why don’t you wear those guayaberas Gonza so thoughtfully brought you from the Caribbean? Just because they are from Cuba! But they are really cheerful, with those little monkeys and palm trees, and that fabric—what can I say? Pure cotton, so cool for coming here on these hot days.

While Lemebel is serious about the crimes of the dictatorship, he never takes Pinochet seriously in an act of defiance.

Pinochet has occasionally appeared on film. Pablo Larraín’s El Conde comes to mind, although it was not well received by Chilean friends of mine. I wonder about the risk of political satire when translated to a cinematic medium, and if in this case, it might have undermined the more serious (and earnest) message of Sepúlveda’s film. I’m curious as to whether either of you felt there was a discrepancy in genre between book and film?

MCS: I agree with Georgina; it feels pertinent of Sepúlveda to have cut the chapters that centre Pinochet—even though I loved them in the book—and substantively, they make great foils to the intensity of the Queen’s romance, though their style is just as intricate, baroque. I have so much admiration for Silver, My Tender Matador’s English translator: I’m in awe at how she wields the flowing, gushing syntax of Lemebel’s divine language:

The splashes of water drizzling down on their fall were multiplied, because they fell, wound up in each other, laughing, struggling, and rolling around in the sand like two little boys who had finally found each other, two children wrestling in order to disguise in their brusque caresses the urgent need to touch, to span the distance across that masculine chasm of sand and ocean.

Georgina, I love your take on genre, and what a wonderful question. How to translate generic codes, forms, structures, expectations; what genres, even, would both book and film versions of My Tender Matador slot into? In the novel, I feel like Lemebel invokes something of the epic in the prose’s heightened rhetoric and recourse to metaphor, and in what Xiao Yue writes of Carlos as almost a personification of ‘freedom, boldness, and promise,’ we find tangs of the chivalric romance. What I can’t locate in the novel at all is the realist mode that Sepúlveda adheres to, which doesn’t mean that realism isn’t present; in the novel, reality is a constraint, a bind to struggle against, as evoked by contrast in the Queen’s dreamy internal monologues. Reality is the surface on which the Queen’s dreams fail. It’s interesting to consider to what extent the film goes to, to stage or otherwise represent the Queen’s digressive thoughts and sensory / sensual experiences, within its commitment to realism. Xiao Yue, what do you make of the realist genre in My Tender Matador?

XYS: Speaking about reality and realism makes me think of an element that operates very differently here between screen and page: music—which is something that always changes the colour of our experiences. Not only is Lemebel’s prose melodious, but he often layers a track into his scenes, whether by inserting the lyrics directly, or by allowing the song itself to act as momentum:

The music wrapped itself around them with its ranchera rhythm. Between the song and their thoughts, political history braided together their emotions: the fears of the young revolutionary on the verge of action and the enamored illusions of the Queen, who closed her eyes as she recited the words of this ballad with a clenched heart. . .

Music (and its constant, dazzling companion: dance) is something that heightens; it emboldens the senses, fortifies emotional resonance, and elaborates the present moment with the depths of sonic memory. I imagine that the experience of reading My Tender Matador would be exponentially more powerful for those who are able to recognise its soundtrack, with its crooning divas and triumphant drumbeats, because music creates a greater sense of reality—a more concrete, awake sense of reality—by providing the clarity of both beauty and temporality. When we listen to a song, the world is fixed to that song for its duration; it is distilled for us alone, and thus made exponentially more affecting.

As for the cinema, I am of the camp that puts great importance on score, so it was interesting to me that Sepúlveda channelled this very loud book into a very quiet film. This is where we find the distinction between reality and realism, of course, because the latter is founded upon neutrality: the classical realist definition of communal time and communal space. There are a couple lovely music-moments under Sepúlveda’s direction (a particularly moving one being the scene in which the Queen and her friends sing together), but largely, he makes very little use of music. It’s a respectable choice, as an overly aggressive soundtrack is largely agreed upon to be emotionally manipulative and cheap, and one that draws attention to just how seriously he took his subject and its overarching message of authoritarianism. The loudness and the boisterousness that we can read in Lemebel’s work is nowhere to be found here—and perhaps that’s why I think the two works are both magnified and intrigued by the existence of the other. Whereas the book shows the unconstrained complexity, floridness, and explosive nature of one’s own reality, the film exhibits the ugliness and monotony of a nation deprived of expression—and thus it is that much more profound when you think about someone like the Queen walking down the streets of Pinochet’s Santiago, with that music playing in her head, giving her so much propulsion, so much joy. One would think that it should be played in the streets.

GF: Reading My Tender Matador in two different languages does feel like listening to two different songs—or perhaps the voices have the same tone and cadence, but they differ in accent, to paraphrase Yves Bonnefoy’s comments on his translation of Hamlet. As you say, Michelle, Silver has a spectacular control of the flow of the text, and she fully understands the political and aesthetic importance of Lembel’s neo-baroque flourishes. And then in the translation from page to screen, there’s a transposition, a change of key. Perhaps it’s a major to a minor key, or a more subtle modulation, but the film has a solemnity; even at the end of the novel, as the Queen bids farewell to Carlos, there is a sense of beauty and power in that tragic goodbye. The power of the Queen’s story is that it contains all these truths at once, regardless of medium or language.

I love what you say, Xiao Yue, that these works are magnified in conversation. The film invites us to take the ongoing political ramifications of the novel seriously, in a world where the existential questions that pursue the Queen are never too far away (I write with the UK’s rollback of trans rights heavy on my mind). I do think the specificity of the setting is magnificently conjured by Sepúlveda; the Santiago of the past superimposed on the Santiago of the present. And the novel of course has that political salience, but never forgets the importance of imagination. We know the world is hostile to trans and travesti existence, but the novel in particular invites us to remember that the world is a construction, an invention, an imaginary just like any other. Many worlds coexist at any given moment, many different presents brush up against each other. Cuba can both be Carlos’s paradise and the Queen’s impossibility. But art offers us the ability to insist on a world of our own creation, a world where we might escape our circumstances and build something more beautiful. Even if we fail, even if, as the Queen says at the end of the novel, ‘it doesn’t matter’, we will continue to try, to insist on the attempt. In Lemebel’s imaginary, there will always be space for transcendence, for eccentricity, for the tender words of an old folk song: those ‘crazy birds / who want to fly’.

Michelle Chan Schmidt (she/her) is Asymptote’s Senior Assistant Editor for fiction and a 2023 Editorial Fellow at Full Stop, where she curated the Winter 2024 special issue on “Literary Dis(-)appearances in (Post)colonial Cities.” She has contributed to The Cleveland Review of Books, Interpret Magazine, La Piccioletta Barca, Public Books, and others. She is the 2025 ALTA Emerging Translator mentee for Poetry from Hong Kong.

Georgina Fooks is a writer and translator based in England. She is the Director of Outreach at Asymptote, and her writing and translations have been published in Asymptote, Hopscotch Translation and The Oxonian Review. She studied poetry translation at the BCLT Summer School in 2022 and is currently completing a doctorate in Latin American literature at Oxford, specialising in Argentine poetry.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet, writer, editor, and translator.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: