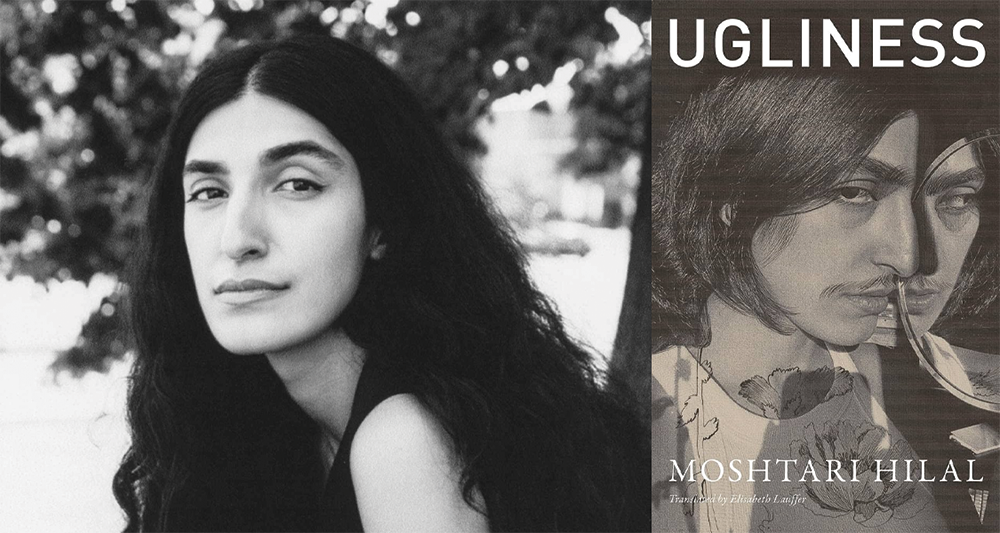

Ugliness by Moshtari Hilal, translated from the German by Elizabeth Lauffer, New Vessel Press, 2025

I have a memory. I’m about twelve years old, standing in front of a bathroom mirror, looking deeply at my body, and making a mental list of everything I could do to “improve” it. The list was ranked by struggle: the easiest came first—tasks that were beyond my control but were relatively simple (get my braces off); followed by items that would require significant effort (lose twenty pounds, maybe more). Mostly, the list lived in my head only to be recited incessantly whenever I saw myself in the mirror. Straighten curly hair. You could call them affirmations, albeit not positive ones, and always in a future tense: I will be pretty. I will be liked. Everything I hated about myself could be altered and remedied, and through this list, my body became a project.

The idea of bodies as projects is central to Moshtari Hilal’s new book, Ugliness, translated into German by Elisabeth Lauffer and published by New Vessel Press in early February. As a woman of Afghan descent now living in Berlin, Hilal examines and takes apart what she calls “the cartography of her ugliness,” an outline similar to my preteen list of remedies. “I divided my small body into enemy territories,” she writes, conducting a clinical analysis of her body and emphasizing what she considered faults. A pointed nose, an incipient mustache, a large head. The accompanying shame. However, contrary to my persistence towards the future, Hilal thoroughly stares at the past. The book begins with an all-too-common experience: childhood bullies. Looking at her school-age photos, Hilal reminisces and makes us think: Who hasn’t felt ugly at one point or the other?

Yet as the book moves forward, Hilal employs her clinical skills to take apart the concept of ugliness, leading us to its birth and attempting to understand how some of these unforgiving Western standards were created, as well as how they contribute to rejection. Sections are titled after body parts or features that can be changed, altered, modified, and reimagined to fit unattainable standards—which Hilal clarifies as being deeply entrenched in colonialism. “The notion of physical self-optimization functions as a technical extension of an ideology that upholds the necessity of shaping people into civilized modern citizens,” she writes. Blending scholarly research, sociology, history, memoir, poetry, and photography, Hilal turns her cartography (and my list) on its head, leading us down a thoughtful and compelling path.

Through a journey that takes her from beauty parlors in Kabul to surgical procedures in Iran, from doctor’s offices in Los Angeles to the depths of social media, where trends and algorithms have inundated us with perfect noses and filtered skin, Hilal traces the sociopolitical patterns that shape beauty and ugliness today. Questioning history, however, doesn’t lead her to easy, trite conclusions in the present. Yes, beauty standards are unattainable. Yes, we know they are based on Western values. Moving beyond these base facts, Hilal’s exploration of the concept of ugliness—and therefore its counterpart, beauty—leads her to examine the whys. Why do we reject ugliness? Why do we fear it? What is it really that we fear when we fear becoming ugly? Poetic and political, attentive and meticulous, Hilal’s genre-bending text is an invitation to face our fears—so that we can finally stop projecting them.

Reimagining the concept of ugliness begets a unique importance on the translation of the word itself. The book opens with an introduction to its philosophy—“It’s about seeing and being seen”—and the importance of the German word hässlichkeit. The first part of that word, häss, means hate; ugliness is rooted in hatred in the German language, but works similarly everywhere else. Lauffer’s choice to introduce the reader to this root is imperative to the book’s core: hatred comes first, and there is no ugliness without it. Her translation subtly addresses this by using parentheticals and bolding the text, enabling the reader to automatically understand the context without being pulled out from the narrative. In fact, throughout the entire work, Hilal’s language is handled with grace, resulting in a prose as powerful as it is interesting, situating it for an Anglophone reader without losing its experimental texture.

The texture of this book is also a way to question predisposed ideas of what is beautiful and what is acceptable—this time not of people but of literature, of narrative structure. Ugliness forms a cadence and architecture that is often unfamiliar in the West, breaking the boundaries of language and of form, function, and storytelling. “It is this hatred’s gaze that stares down our face in the mirror. The gaze that nestles inside us and watches others. It is the hatred occupying and observing us all,” Hilal writes, and then breaks into verse:

I place the blade to my skin and destroy the evidence.

Even fixing my nose is just a slash of the scalpel away.

Why do I set the blade against my cheek,

When what needs real correction is this hatred?

The text’s shape, then, embodies what it represents: a rupture from the homogenous, of what we have been told is right, what is beautiful. It’s refreshing to get our hands on literature so daring, so fearless.

Hilal, however, doesn’t seem overly focused on the language surrounding ugliness. She doesn’t want the reader to simply change the way they speak or interact with whatever they consider to be “ugly.” “My book is not a critique of language,” she told Theresa Weise in an interview for Various Artists, “I don’t believe that language is the sole problem. Ugliness is not created by how we use words like ‘ugly’ and ‘beautiful’ but by living conditions and structures of discrimination.” Rather, the text is an invitation to recognize, observe, and acknowledge.

Although at times dense and slow, Hilal manages a deep interrogation of the endless, historical fascination with the ugly. “The demand for displaying aberrations from the norm extends back to antiquity,” she writes, putting the lens on so-called freak shows and museums that exhibited monsters. We have seen the ugly as a phenomenon, one that we want to conveniently avoid. Although people will want to observe the ugly, they also reject it at their whim—they would rather be dead than ugly. “We seek space between ourselves and the things we don’t want, don’t want to become, don’t want to be,” all the while still conveniently participating in the systems that create this. But then again, is this behavior hypocritical, or is the contradiction a symptom of the deep entrenchment of such ideas?

Precisely as Hilal pushes her readers to think about how twisted it is to continue working on our bodies as projects, she admits to falling for it herself. When she gets press photos taken for this very book, she sees a “sad face looking back at me: my skin is dirty, dry, orange. My photographed eyes are tired and throw me back to the start of this book, back to my beginnings—fourteen ugly mugs at fourteen years old. Have I not learned anything?” Guided then by this stubbornness, she fearlessly investigates the root of our fear to be ugly, uncovering layers that would serve as a valuable reflection for anyone interested in understanding the world and our place in it.

As Hilal looks back at the photos that she rejected as a child, a poem encapsulates the pain of looking back upon what she once thought was ugly:

I dig up that photo for this book.

I search in vain

for an ugly horseface.

All I find is the picture of a child

flashing her teeth,

smiling for what will be the last time

in fourteen years.

In this, she shows how the shedding of self-hatred is not just about learning to love ourselves as if the solution were merely individual. If self-hatred is rooted in the violence of our ancestors, then it demands a simultaneously individual and collective process of recognition.

Miranda Mazariegos is a Guatemalan journalist, writer, and translator. She began her career at NPR, contributing to programs such as Radio Ambulante, Consider This, Throughline, and All Things Considered. Her work explores the culture, history, and politics of Latin America. She is an MFA candidate at Columbia University, where she’s working on a collection of essays and teaching through the Undergraduate Writing Program.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: