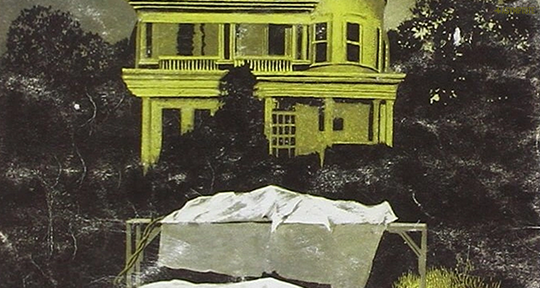

Italy’s lauded Michele Mari was first introduced to the English language via a collection of thirteen short stories, published as You, Bleeding Childhood; through translator Brian Robert Moore’s rendering of Mari’s singular voice, readers were able to enter a vertiginous realm of obsessions, hidden psyches, childhood revelations, and wondrous horrors. Now, Mari and Moore are returning with Verdigris, a novel that further displays Mari’s masterful construction of mystery and fantasy with the story of a young boy, Michelino, and his developing friendship with a strange groundskeeper, Felice. The translation earned Moore a PEN Translates Prize earlier this year, and in the following essay, he gives us some insight into his process, and tells us why Mari is deservedly recognized as one of the most important Italian writers today.

When I first encountered Michele Mari’s Verdigris (or Verderame in the original Italian), I experienced something rare, wonderful, and a little bit eerie that I’m sure most avid readers can relate to: the sensation that a book was somehow made for me. Its sense of otherworldly mystery, its dark humor, and its beautiful, inventive style all came together to form the exact kind of novel that I could gladly get lost in for ages. It likely would have been the first book I’d have tried to translate, had it not seemed beyond my capabilities at the time. But all books, especially the really good ones, seem impossible to translate until you sit down and somehow translate them, and so I eventually decided to make an attempt. It was too captivating a novel and too glaring an absence in the Anglosphere, and I hoped my own enthusiasm and love for Mari’s work might carry me through.

The first major difficulty in translating Verdigris is Mari’s use of wordplay, which, rather than appearing decorative, often plays a very direct role in the novel’s plot—a plot that is as intricate as it is engrossing. I realized there was no way around being particularly visible as a translator in order for this novel to reach anglophone readers: one could either rely heavily on the original Italian wordplay and speak directly to the reader through explanatory footnotes, or assume an even more active role and try to recreate Mari’s fluid inventiveness in English. Hoping the book could remain as immersive in English as it is in Italian, I opted for the latter approach throughout. To do this, it was essential to keep in mind not only the novel as a coherent whole, but also Mari’s broader autobiographical and autofictional body of work. Any literal changes had to remain consistent with his personality both as writer and as character, and I was fortunate to be able to run all of my solutions by him. Finding English equivalents for puns, word associations, and, most of all, anagrams takes a great deal of thought but also an incredible amount of luck—or, in the case of this book, maybe there was something else at work, and the fact that almost uncannily fitting solutions could be found in a completely different language had to do with the mysterious and occult forces invoked within the novel. For me, living day by day, for an extended period of time, in the world of Verdigris meant partially believing such things.

I took the same immersive approach for the novel’s use of dialect. Roughly half the book is dialogue, especially between the character of young Mari—called Michelino—and Felice, an old groundskeeper who turns to Michelino for help in order to fight his worsening amnesia and to fit together the clues of his largely forgotten life story. The Northern Italian dialect spoken by Felice in Mari’s Verderame is not particularly realistic, but rather literary, geographically amorphous, and partly invented. I broke from what might be seen as conventional wisdom and, instead of losing or flattening linguistic differences and idiosyncrasies in translation, sought to use a somewhat unrealistic vernacular in English that would feel just as expressive as Mari’s original. At the same time, the idea of having the character speak a relatively standard English, with a sprinkling of Italian dialect words here and there to convey the idea of difference, struck me as particularly jarring and unappealing; by this method, Felice would have inexplicably bounced between two different languages, his most characteristically evocative phrases and exclamations becoming literally meaningless to the anglophone reader. Instead, I hoped Felice would feel fully formed in English, speaking his own personal vernacular which, importantly, separates him from all the other characters in the novel. This was ultimately the only option that seemed in keeping with the novel’s conscious riffing on literary tradition, especially in relation to nineteenth-century works of horror, mystery, and adventure, and that respected Mari’s own reputation as one of—if not the most—linguistically interesting and entertaining authors writing in Italian today.

Throughout Mari’s novel, Michelino interprets the world with the help of the books he has read. Gradually, like a little detective, he finds himself trying to solve a mystery that is both more fantastical and more horrifying than anything he has encountered in novels, while history reveals itself as the greatest nightmare of all. In Verdigris, Michelino’s most terrifying hopes, his most cherished fears come to life all around him—all I could hope to do as a translator was to make this book come alive for English readers too.

Brian Robert Moore is a literary translator from New York. His translations from the Italian include A Silence Shared by Lalla Romano (Pushkin Press), and You, Bleeding Childhood and Verdigris by Michele Mari (And Other Stories). He is the recipient of awards and fellowships from the National Endowment for the Arts, PEN American, English PEN, and the Santa Maddalena Foundation, among other institutions. His translations of Michele Mari have received two PEN Translates awards and have appeared in publications such as The New Yorker.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: