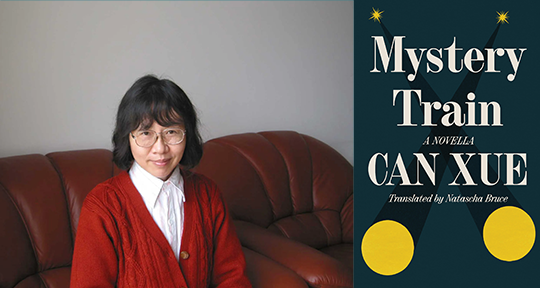

Mystery Train by Can Xue, translated from the Chinese by Natascha Bruce, Sublunary Editions, 2022

To board Can Xue’s novella, Mystery Train, the reader must surrender entirely to a world plunged into eternal night, where characters give themselves up to be devoured by wolves and execute perfect needlework in pitch-black darkness, where fear and worship surround a power figure known only as the conductor, and where many are unable to make any sense of the cruelties perpetrated upon them. Can’s Matrix-style text offers little answers, opening up instead a multitude of unsettling questions about the body, induced guilt, and the illusion of choice.

In her introduction, Can (the pseudonym of Deng Xiaohua), is generous enough to provide a warning to the unsuspecting reader: “We might decide that the life the artist is describing belongs to someone else, and has nothing to do with us. But it does have to do with us—because, for us, the people of the new millennium, the body-soul contradiction is vitally important.” Indeed, Mystery Train can be read as a fable on the struggle between the presence and demands of the body—down to its most basic instincts such as sex or bowel movements—and the incessant inquiries of the soul, which demand explanation yet continually fail to culminate in satisfying answers. The author goes on to explicates the purpose of this work in the short introduction: “Mystery Train characters suffer, but never in vain. Hardship forces each one to grow, and mature, and to become tougher than they were before. Gradually, they form themselves into responsible, creative individuals. The veiled yet nevertheless intense longing for death that pervades the story is in fact a longing for performance—for a death-defying stunt played out on a clifftop.”

As promised, Can is not tender with her characters. The protagonist, Scratch, has been working on a poultry farm; the train is taking him on a business trip to a remote city in the north of China, bordering Russia. He soon discovers after boarding his train, however, that he has most likely been fired—but nothing is clear. He recalls a strange send-off by the farm’s boss: “At the bus stop, the manager grasped Scratch’s hand in his own callused one and said, with strange formality, ‘I’m sorry. I haven’t taken good enough care of you. Please forgive me.’ Not yet sixty and already going senile, thought Scratch. It made no sense. Why all the emotion? He was hardly being sent to his death.“ In such short, sharp sentences, Can builds an atmosphere of oppression—a sense of imminent danger in a forest of undecipherable symbols and signs.

As Scratch gets comfortable on the train, strange things begin happening to him, and he meets a series of characters whose words and actions go on to confuse him even more. There is the conductor, who becomes more enigmatic the more Scratch gets to know him: “His appearance was misleading, just as everything he said was deceitful. He kept repeating these tedious stories precisely because he knew they were meaningless, and the ideas he wanted to express were buried underneath the tedium. But they were buried too deep for even him to reach. The trouble was he couldn’t think of any other way to express himself, and so he kept on and on with the same futile exercise.” There is also a truly scary woman, Birdie; a train kitchen assistant with only half a face, she is endowed with a robust sexual appetite, and quickly turns Scratch into her lover. Towards the end of the first part, “On the Train,” Scratch comes to realize that the vehicle has stopped in a tunnel engulfed in darkness, deepening his sense of utter disorientation.

In the second part, entitled “In the Wilderness,” Scratch soon finds himself in a community of people living in tents under an eternally black sky. There, he continues to encounter the conductor and the half-faced woman, but also makes acquaintance with another mysterious individual, the seamstress: “It felt as if she was both seeing inside him and also not seeing him at all, her gaze almost vacant. . . He felt that everything he had lived through before this moment was meaningless, and that a huge expanse had opened up before him. But what that expanse was, and how he was supposed to navigate it, he had no idea.” The world around Scratch becomes even more incomprehensible, and the short conversations around him resemble absurdist poems by Russian poet Daniil Kharms: “‘The woman?’ said the electrician. ‘I don’t really know her. She was going round the train mending quilts in the dark. Apparently she’s a very talented seamstress.’” The seamstress, too, speaks in similar riddles: “My needlework is mental exercise —I stick the needle in and then I pull it out, and it’s like I’m pulling something out of my brain.”

Later, the hero witnesses how some of the characters—including the conductor and the seamstress—leave the tent and are devoured by wolves, while moaning with what sounds like pleasure. Can’s description of extreme violence is a recurrent theme in her work, and she has a clear vision of its purpose, as she explained in a past interview: “Writing violence for the sake of violence is vulgar and tasteless. . . Your depictions of violence must have form, must have a sense of metaphysics to them. Just like the images in Dante’s hell, they must depict the true struggles deep within the soul.”

Can’s prose is often described—including in her own words—as experimental. Language is twisted till it loses its threads: “It was still pitch black, with no sign of a cooking fire, exactly the same as yesterday. But what was he doing thinking a word like ‘yesterday’? There was nothing to suggest this was a new day.” For the author, the deconstruction of language allows her to explore themes close to her oeuvre, but also to her personal experience: guilt without wrongdoing, the deception of choice, and the moral obligation to question everything about a person’s life. Translating Can Xue’s sharp language into English is not an easy task, but Natascha Bruce has found a tone and style in English that perfectly match the author’s voice and intention.

Can comes from a family of intellectuals who were persecuted during the Cultural Revolution, wherein people were accused of imaginary crimes, and also forced to confess profusely to such transgressions. In this traumatic vein, Scratch often wonders about his possible mistakes: “Had he somehow offended the conductor during their talks yesterday, to the point that he felt the need to retaliate? He couldn’t think how, especially as their interactions hadn’t even been conversations. . . He tried his best to remember all the conductor’s stories, in case there were clues he’d failed to notice.” Later, Scratch comes to the conclusion that one has to admit guilt without any explanation: “And now, for reasons he couldn’t understand, he was evidently in some kind of trouble. In which case, his priority shouldn’t be trying to understand the reasons why.” This evocation of Kafka’s The Trial is no coincidence; Can is a great connoisseur of Kafka’s works, and has written a series of essays dedicated to the Prague author.

Another favorite theme of Can’s is the concept of choice—particularly whether people can make responsible ones, or if they would rather happily and lazily forgo that right. Here again, the main hero reflects on his decision-making process and comes to a rather pessimistic conclusion: “When the farm manager first told him about the business trip, the set-up had been full of holes. A little digging and the lies would have been obvious, but he hadn’t even tried to expose them. He’d simply boarded the train, no questions asked. And when he was on the train and first realized something was wrong, he could have turned back but he didn’t.” Despite this dark outlook, however, the author manages to introduce a glimmer of possible redemption in the very last pages of Mystery Train, iterating that accepting the illusion of choice might bring some better understanding of the meaning of life. As she writes: “The future was still uncertain, although his understanding of what might happen was substantially different than when he’d boarded the train. Back then he’d been puzzling over how to get away from everyone, whereas now he had to just take things as they came.”

A true modernist, Can concludes with an invitation to abandon the past and stay in the here and now: “‘Have you heard of the mystery train?’ he asked. Then he gave me a strange look and said, ‘I forgot, of course you haven’t. I’ll tell you this: it’s a mysterious train that charges endlessly around this vast territory of ours. All its passengers are there by mistake. They boarded the wrong train but they’ve never even considered getting off. Why? Because the train has magical powers. A person steps inside it and immediately forgets everything that came before. All they care about is what’s happening right in front of them.’”

Filip Noubel was born in a Czech-French family and raised in Tashkent, Odessa, Prague and Athens. He has worked as a journalist and media trainer in Central Asia, Nepal, China, and Taiwan, and is now managing editor for Global Voices Online. He is also a literary translator, interviewer, Editor-at-Large for Central Asia for Asymptote, and guest editor for Beijing’s DanDu magazine and the New Welsh Review. His translations from Chinese, Czech, Russian, and Uzbek have appeared in various magazines, and include the works of Yevgeny Abdullayev, Radka Denemarková, Jiří Hájíček, Huang Chong-kai, Hamid Ismailov, Martin Ryšavý, Tsering Woeser, Guzel Yakhina, and David Zábranský amongst others. In 2023, he launched The Vernacularists, a podcast on linguistic diversity and power relations among languages. He is usually based in Prague, Tashkent, and Taiwan.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: