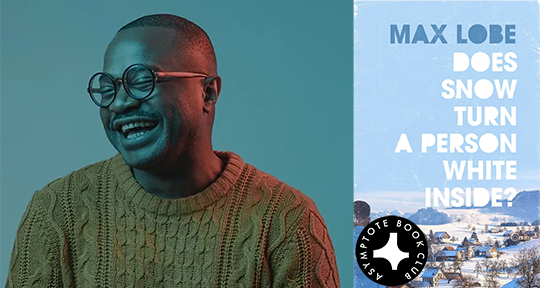

For our final Book Club selection of the year, Asymptote is proud to present a work emblematic of how writing can transform, subvert, and negate borders. In Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside?, Swiss author Max Lobe traces how the complex factors of race, class, sexuality, and migration can cohere in a single life, and how nationhood can be refracted and reinterpreted by those who refuse to be defined by the standard. Speaking in the extraordinarily vivid voice of his protagonist, Mwana, Lobe balances tragedy with joy, freedom with entrapment, and home with home.

The Asymptote Book Club aspires to bring the best in translated fiction every month to readers around the world. You can sign up to receive next month’s selection on our website for as little as USD20 per book; once you’re a member, join our Facebook group for exclusive book club discussions and receive invitations to our members-only Zoom interviews with the author or the translator of each title.

Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside? by Max Lobe, translated from the French by Ros Schwartz, Hope Road Publishing, 2022

As in love, mystery, and metamorphosis, the name of country draws a long throughline in our world of stories. Add to it a possessive—my country, your country—and the resulting narratives are instantly elaborated with the ontological intersections, demarcations, and dialogues that enmesh our landscape. Through this simple addition, a life is juxtaposed with a society, a single act comes to emblematise a culture, and an experience constitutes an identity—not necessarily out of any active political consciousness, but simply from having left, at some point, that arbitrary and mutable shape of one’s birthplace. Paul Gilroy, in conceptualising diaspora, described it as positing “important tensions between here and there, then and now, between seed in the bag, the packet or the pocket and seed in the ground, the fruit or the body.” To move across our jigsaw world is to know the fluid weight of difference and sameness—that they can be at once interchangeable and oppositional. These shifts from strangeness to familiarity do not begin with the boarding of a plane or a boat, but occur in minute swatches of conversation, in the passing from one minute to the next, between two people looking out at the same scene, not knowing what the other sees.

In Max Lobe’s Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside?, translated from the French by Ros Schwartz, country is introduced by the most immediate and intimate of desires—food. Our narrator, Mwana, is lugging “two huge sugar-cane bags” across Switzerland, with all the provisions and gifts of another nation inside: “Fumbwa, saka-saka, makayabu, okra and dried impwa.” The list goes on, rich with sugars and starches and svelte oils. Wrapped meticulously by his mother, the treasured packages have been carried by his sister Kosambela, across the continental divide from what Mwana calls Bantuland, to the nation where they both now reside: Switzerland of the Grütli Meadow and the Rütli Oath, of white-out peaks and lakeshore villas.

A recent graduate of the University of Geneva and a settled Swiss resident, Mwana is black, queer, and unemployed; it is this lattermost factor that rules his life, his daily preoccupations, and his physical and mental wanderings. With repeated trips to the unemployment office, small yellow coins dug out of household crevices, kindly deceptive calls to his mother—this scarcity is the precipice that Mwana dangles from, and as such it is the swinging, breakneck angle by which he interprets everything. The two bags he drags onto the bus from Lugano to Geneva contain emblems of home, of care, and of a beautiful eradication of distance, but most importantly, they are an antidote to hunger. Amidst Lobe’s warm, loquacious prose, we first see the dissipation of difference into sameness, the shift from displacement in country to immediacy in the body. In all the discursive paths the mind takes to arrive at a single place, we see the need to live.

Race, sexuality, and class form a geometry that resists any equilibrium; there is never really any way to talk about one without talking about the others, and the links between them are indiscernible, capricious, and explosive. To open up poverty is to open up migration is to open up blackness is to open up the love between two men. The investigation of these vast dialectics, then, must involve a great deal of humility, an acknowledgment of epistemological limits, and an understanding that any overarching idea can be immediately unfounded and reiterated by another—there is no static table upon which these reverberations of identity can be charted. Here, it becomes clear that fiction is privilege to a grace that theory is not; storytelling does not call for the distillation of a vast network into the foundation of a fact. In the testament of a life, worldly materiality and contradictions can be coalesced seamlessly, because living is not an aggregate of factors and elements—it is the drawing of a line down the long plane of time, and time is that shapeless container to which everything conforms.

So it is in the mind—Mwana’s wandering, constantly occupied, multifarious mind—that this novel takes place, and it is in the annals of his mind that all those byzantine conundrums of human existence are relegated to background. Ros Schwartz’s exuberant, wonderfully paced translation of Mwana’s inner monologue must be credited here; the language traverses the same multifarious, fluent tracks of thoughts running wild, without ever submitting to tiresome self-absorption or performative soliloquy. Mwana gets distracted, mixes emotion with logic, spills his own secrets, and makes light of tragedy. He does not, however, linger on being a diasporic African, or the bias ingrained in the labour market, or the man that occasionally makes his couple a throuple. Neither does he debate his partner, whose wealthy family is more than capable of helping them escape their financial misery, nor incites any conflict with Kosambela, who asks for divine forgiveness after accidentally attending the engagement party of a gay doctor. There is no requisite to answer the Big Questions within the frame of this story, because one assumes that Mwana has worked at it, in some way, all his life.

When Mwana finally does land a temporary work placement at an NGO, he finds himself in the position of fighting against the anti-immigration “black sheep” posters that have been plastered across the country—a poster that Mwana initially has very little reaction to, besides thinking it “quite funny.” Led by the vibrantly dressed crusader for justice, Madame Bauer, the black sheep situation is deemed extremely serious, and ignites a great deal of righteous anger (as well as righteous defensiveness) from the more left-leaning Swiss:

I can see that Madame Bauer takes great pleasure in vehemently criticising the black-sheep poster. ‘It’s outrageous!’ she exclaims between arguments punctuated with the recent history of humanity. She vaunts the values of solidarity, respect and humanism. When she evokes those values, the traits of my Bantuland people, I say to myself that she must be the most Bantu of all the Swiss.

But as the commotion and consequences of the poster continue to rise, as arguments break out on trains and deportation advocates push to send cross-border workers back to France, the narration continually returns to a single, unbearable reality:

I’m hungry.

Despite the fact that his presence in this country is at the centre of this political discourse, Mwana is apart from it—alienated from the abstract construct of his migration by the physical demands of subsistence. The cartoon sheep that colour the poster are figments; they don’t starve. There is an irony colouring all of this sheep business—the public displays of anger, the well-to-do NGOs, the demonstrations alighting the streets—but it is never bitter, never cynical. Unlocked from an ideological framework, Mwana does not serve any liberal tradition, is relieved from any ethical labour, and as such, he defies the fact that he has been invented, that he is a character in a book, written by an author who shares his background, in the context of our urgent time. As Monica Ali once wrote, “The protagonist cannot be otherwise, cannot do otherwise, and yet he is condemned to behave—as we all must—as if he were free.”

Those who write the art of make-believe know something that politicians and ideologues perhaps do not: that messages never arrive at their destinations unscathed, transmitted perfectly from end to end. In the enormity between sender and receiver, there is a world of interruptions, of noise, of conflicting signals, and when novels harness this polluted complexity, human figures take shape. The empathetic impact behind Does Snow Turn a Person White Inside? is not a direct insistence, nor is it a bear-all vulnerability; it is the all-too-simple notion that the person sitting beside you at the bus station, standing behind you in line at city hall, waiting around in a hospital hallway—they are not unreachable. They are present. But they are not representations or hallmarks, and they have no obligation to explain the world that they live in to you, because that is the world you live in too.

Midway through the novel, the tenets of Mwana’s life are upended. His mother, Monga Minga, is diagnosed with terminal cancer, and she moves to Switzerland to seek treatment. Face-to-face with the maternal body of country in a hospital bed, the past leaks through: the betrayal and death of his father, the celebratory Bantu ululations at his graduation ceremony, the exposing of his sexuality by a nosy aunt. But all this is parsed along the same linear ongoingness of the present, in directions and misdirections of thought at its exhilarated, musical pace, connecting all the disparate realms of personal history in the symphonic moment. In Monga Minga’s displacement from both her country and her vitality, surroundings are rendered meaningless. It does not matter if she dies in Bantuland or in Switzerland, except to those who watch over her. Meanwhile, Mwana continues to go to the food bank, the unemployment office, the desk at the NGO, and he reminds himself over and over that place dictates everything: what can be felt, known, or had. At the hospital, he recites the law: “No laughing here. You mustn’t laugh here. Here, there is sickness. Here, there is disease. Here, people are sad.” I was often reminded of Gilroy’s allegory in such passages—seed in the ground, the fruit, or the body. One is tempted to say that it’s all the same, but a seed that cracks between the teeth is not the same as a seed that bears the promise of fruit. And yet—the seed is never not a seed.

Edward Said defined exile as a constant “urgent need to reconstitute. . . broken lives,” but there is no evidence of that in Mwana. What can be considered broken in his life is not his absence from the country of his birth, but the more enduring fractures that know nothing of borders—illness, poverty, and the desire for a better life, not a different one. Outside the expected schism of immigrant trauma, it is perhaps a more contemporary, less rigid view of what nationhood and diaspora mean. In it, we are able to live in one country without trying to banish the other. We can speak one language using the words of another. We can be accountable not to where we live, but to how we want to live.

At the depths of his job-hunting misery, Mwana plans to call Monga Minga, and he dreams:

I’m going to make up the most outrageous stuff: that soon I’ll be sending her some shiny gombo, loads of it. That I’ve just found a very well- paid job in a major international corporation based in Geneva. That soon I’m going to buy myself a very big villa on the shores of Lake Geneva, or a mountain chalet in Davos. That I’ll visit her in Bantuland every month and even every weekend if she likes. I’ll even tell her that my companion is a few weeks’ overdue and that soon he’ll be giving birth to a beautiful baby. That she’ll have the honour of rocking this first ever child born of two biological fathers. That she’ll be able to take it to school, cook it a dish of cassava with a palm-oil-based sauce, sing it Bantu lullabies and tell it tales from the Grison Alps, which she’s never seen.

Here, within the imagination, is a reincarnation of country—at once a place on a map and one in the mind, a root that holds deep to the earth and an object carried on the shoulders. People known and people imagined, places real and unreal. That is where we live: in everything we have lived through.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet. shellyshan.com

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: