In Antena’s “Manifesto for Ultratranslation,” it is stated: “The politics of translation make us ultraskeptical and ultracommitted.” As such, the discourse and dialectics surrounding this artform are in an ever-evolving state of being challenged, argued, and explained. In the following conversation, Blog Editor Xiao Yue Shan discusses her work in editing Chinese language translations with fellow translator Zuo Fei, touching on their separate values, priorities, and approaches.

Xiao Yue Shan: Translation is an intensely personal experience—perhaps the most transparent reflection of what occurs when idea is transmuted through the individual mind’s various channels. This is why we, as translators, are continually struck by our work’s mutating forms, its evolving methods, and continue to conversate with such intensity about our own logic; when one speaks of translation, one speaks of a way of seeing the world. When we were editing translations together, you wrote me a letter in response to some edits I sent on a final draft of some poems; in it, you stated that you believe in literal translation, in seeming opposition to my approach of preserving the ineffable by creating anew.

It’s interesting because we are both poets, and I’ve always assumed—presumptuously—that poets are all apart of the same passionate investigation, in which consciousness touches something and brings it to life, shaped in a precise and resolved concentration of words. In translation, there is no transposition of this consciousness, which is a singular encounter between the poet, their knowledge, and all that it reaches and contacts. So, the translator must take the place of the poet, and—with intelligence but without egoism—give the original poem something it can live with.

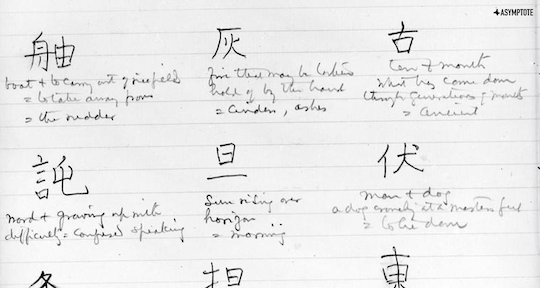

Essentially, there is a distinction between a poem’s components and its poetics. It seems to be a corrupt exchange should a text be translated word-for-word, when one acknowledges the multiple roles that words play in literature; they do not simply transmit meaning, but also voice, history, and music. Could you tell me why you work from a more literal approach?

Zuo Fei: I prefer literal translation to free translation simply because, in the time of science and technology, people believe translators should strictly follow the original text. By literal translation, I don’t mean word-for-word, which does not work for poetry in many cases; my intention is that we should adhere to the original work as much as we can, and put it into a target language according to our desires. That is to say, if translation is an impossible job, we try to increase the odds of it being possible.

I think many agree upon the three rules set by the Chinese translator Yanfu 严复:“信, 达,雅”— commitment to the original, accessibility for target readers, and congruity in style. I guess the first is being as literal in translation as possible—which was not an easy goal to achieve for early translators. For instance, Liang Qichao 梁启超 turned Byron’s poem “Woe to Greece” into a political novel, hoping to raise the awareness of nationalism and set a trend for the young translators of his time.

As for the second rule, I think Eugene Nida’s functional equivalence theory can be used to monitor accessibility for the target culture, but the criterion he sets for equivalence is perhaps too high. He argues there are four level of equivalence: lexical, syntactic, textual, and stylistic—I suppose a translator must possess a certain level talent or capability to achieve any of them.

As stated by Li Yongyi 李永毅—the Chinese translator from Latin of Horatius, Ovid, and Vigil—translation is an art of regret, and translating poetry is an art of cruelty. My understanding is that a translator can never be happy with themselves nor their works. For example, Chen Ning 陈宁, who was enamoured with Rilke’s poetry, and dedicated himself entirely to its translation. He learnt the German language, collected meticulously all the information about Rilke he could get from around the world, spent every penny he had for the cause, and died young as his health deteriorated. He became a martyr for the cause of translation, but his translations of Rilke have received only mixed reviews.

In the social media era, a lingua franca is badly needed. But the failure of the Esperanto shows that a universal language would not survive if it were not a natural language. These days, we often have to turn to machine translation for immediacy and expediency, but even if translation apps were perfect, I wouldn’t be satisfied if they continually produce identical iterations. Even though I’m perpetually upset that a certain translation of mine remains dissatisfying for either myself or its readers, I’m optimistic that someday, I’ll be able to create a different and better version. It seems to me that the world is a better place to live in simply because we translators are eternally making contributions to the Tower of Babel.

XYS: I think it’s interesting that we speak so much of translation in terms of merit, when criticism of an original text is never factual; we criticize works of literature based on the world they’ve arrived in, not from where they came. Someone else has put together a world for us. We do not tread in that world searching for error, but for connection, and any failure of a connection is not based on the contingencies of correctness, but rightness. Translations, however, are measured first from their originals. We are naturally suspicious of imitation—it is instinctual to reject the copy, to demand the original. Translators, then, are force-fed the dictum that their productions be seamless. One has to be absolutely correct; only then can rightness be within reach. One cannot cheat the reader.

But the ideal is poisoned at its very fundamental level, which is that there is no correct reading. Reading is an amalgam of intelligence, knowledge, reference, and experience—all contributing to its subjectivity. We demonstrate this even with identical books, which upon repeated readings will gain a different light, and I think this resonates deeply with what you’ve said, about a translator being able to go back to the same text time and time again to make what they believe are improvements. All translation, then, is the effort of ego to justify itself; the ego saying: I know I was meant to disappear, but I couldn’t.

Of course, at the minimum, the translator should be an expert of the destination language, but expertise does not denote talent. Could we say, then, that the translator must be as equally talented in their language as the original writer is? But then we veer into a whole dialectic about the convergence of intellect and taste. Style is an impossibly fragile thing; I am never reminded more of this than when I see the perfect blocks of Chinese poetry matted out into long, dangling strands of English lines.

This leads me back to the translator as a reader first. They must be able to decipher what Nabokov called this “exchange of secret values”. For it is a mystery how words proceed, how they conjure, how they manifest. It seems to me that the most wonderful cases of translation are sourced from readers who lock into this magic, as we can only translate what we respond to. The desire to have a text live on, live longer, live more variously in other languages, is an intoxication of discovery, and it is this that needs to stay intact: the powerful, quiet affinity between writer, reader, and world.

I’m curious as to what you think are the particular difficulties of translating Chinese into English and vice versa.

Zuo Fei: I’ve done more translations of poetry from English to Chinese, rather than the other way around, but I somewhat agree with your point that translating is a response to reading. As a translator, you have to believe that your interpretation—since you’ve presumably put more work into it than most others—is the most authentic one. What an absurd idea!

As to the particular difficulties in translation, I don’t think it’s easy to make a list, as there is no way to truly analyze how a mind works. But let’s suppose there does exist such a mysterious land, and we are capable of at least partially mapping out the journey, so as to survive the uncharted woods.

The most difficult part is style. You might be right in arguing that style is more of talent than of expertise, but in the reproductive aspect of translation, one has to be highly aware of the style, capable of deciphering its genetic information, and thus able to create a similar offspring by imitating the traits. Of course in practice, we are hardly able to break style down into certain components; rather, we just set a general standard of the text’s vibe, to be followed in the translating process. For any narrative, the style is how one author is distinguished from another. It is as light is for photography, and color for painting.

When my co-translator Jennifer and I worked together on a long poem called “The Butterfly” by the veteran Chinese poet Hu Xian 胡弦 (winner of the Lu Xun Prize for Poetry—China’s Pulitzer), the first thing we talked about was the style. The language is laconic, sententious, but vivid at the same time, using the butterfly as an allegory for such subjects such as life, history, et cetera. Although the poem uses ordinary words, we knew the point was to show the poetic power expressed by those words.

This was not the case when we worked on a poem a young poet, Qige Tuoma, called “Dante’s Request”. On the lexical level, the poem is formal and literary, and words with opposite or similar meanings are juxtaposed to form controversial or paradoxical expressions. The piece resembles to a degree certain postmodernist poems, with a pool of metaphysical vocabulary knitted tightly together by intellectual reasoning. I suggested to Jennifer that she read read Carl Philip’s “Ghost Choir” to better understand the arrangement of the lines. It seems excessive, but if we do not pursue the excessive, we’d be no better than those who argue that poetry cannot be translated at all, and what a disastrous world that would be.

Another difficulty is the load of cultural connotations. “Small Town Factory” by Xie Juexiao 谢觉晓has quite a few words closely related to a specific cultural phenomenon, either in China overall or for localities in the deep south: 黑摩的,清玩,寒斋,朱梅鱼. For the translator, Ben Thompson, the first term was not too difficult to interpret (“pirate tuktuk” is what he worked out), but the second and the third, considering the context, are particularly opaque; they are terms used by the author to satirize the trend of feigning sophistication by showing interest in ancient Chinese culture.

The English lexicon of “Small Town Factory” was also meant to match the rhythm the translator created for the poem. Most contemporary poetry is free verse, but music is always a difficult task we try to perform in translation. It’s almost beyond explanation, but we are both poets—each word has to be pleasing to the ear, and we understand the radical impact of small things.

Xiao Yue Shan is a poet and editor. The chapbook, How Often I Have Chosen Love, was published in 2019. The full-length collection, Then Telling Be the Antidote, is forthcoming in 2022. She is the English Editor-in-Chief of Spittoon Literary Magazine. shellyshan.com

Zuo Fei is the Chinese language Editor-in-Chief of Spittoon Literary Magazine. She runs a platform, 外国诗歌精选, that introduces foreign poetry to Chinese readers. Her work appears in the likes of Poetry of Jiangnan, Mountain Flowers, Youth Literature. Her collection of essays is forthcoming from Guangxi Normal University Press. She received a MA from Beijing Foreign Studies University in 2000.

*****

Read more on the Asymptote blog: